Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

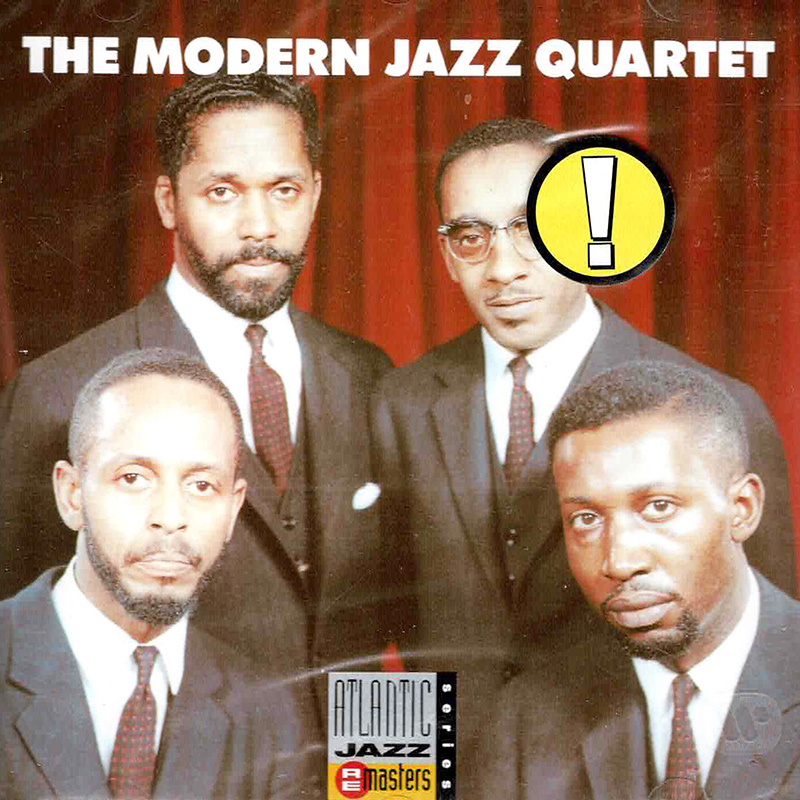

The Modern Jazz Quartet

Night in Tunisa

- The Modern Jazz Quartet - Night in Tunisa

- 01. Medley;

- They say it's wonderful

- How deep is the ocean?

- I don't stand a ghost of a chance with you

- My old flame

- Body and soul (10:15)

- 02. Between The Devil And The Deep Blue Sea (6:56)

- 03. La Ronde (2:12)

- 04. Night In Tunisia (6:10)

- 05. Yesterdays (5:11)

- 06. Bag's Groove (5:43)

- 07. Baden-Baden (4:04)

- The Modern Jazz Quartet - group

John Lewis, musical director of The Modern Jazz Quartet, is an enemy of complacency. fie and his J colleagues rehearse at least two or three times a week when they are not chained to a schedule of one-nighters. During a three week stay at Music Inn in the Berkshires in the summer of 1956, the MJQ rehearsed daily - the lure of the lake and other sun-lit diversions notwithstanding. The reason for this continual honing of their material and themselves by the MJQ; is that John is a musical director who knows exactly what he wants, and will not rest content until he and the group fulfill the potential of any given piece: of their own collective identity: and of their individual .skills. A corollary of this attitude is John’s disinclination tip express more than guarded satisfaction with most of what the unit has done on recordings. When, therefore, he said with his customary gentle firmness that this album is the heat the MJQ has done musically, I was curious to discover whey he felt able to make what is for so lightning-bolt a declaration. "I like the album," he began, "because the selections are old in our repertoire so that. we've played them a great deal. 'they're old enough for us to see if we can play, if we can really get out of them and. out of ourselves what is there to be gotten. After hearing; the album, I feel we can play:" "This album," John continued, "is one of our characteristic J0-minute sets. That's a long time to play and sustain interest and strength. I feel we did here. And the rhythm holds up, all the way Another reason I like the set. The numbers also sound the way they actually do sound when we are at our best in a club of at a concert. Again, we've played them so long that we know how we want them to sound." It will be. noted that there is a considerable amount of solo playing in the set. "We had to play for that, to be able to do that," John explained. `They went for themselves, but that was possible because the quartet before had done so many pieces under direction. They knew what to do and I knew what to do when going for ourselves." There are several ballads in this collection, and John has pointed to a note on the ballad in jazz by . John Wilson (Ballads & Blues/Milt Jackson) as most clearly expressing his own ideas on. the subject. "It is the ballad," Wilson wrote, "as most of us have learned, that separates the jazz improviser from the jazz drudge. It is possible to swing a ballad forcibly enough to invest it with an appearance of jazz feeling, but in the process much of its balladry is dissipated. Or, if they inherent prettiness in a ballad is top carefully retained, the effect may be more funereal than jazz like_" Wilson went on to indicate that Milt's task in that album was "to keep the ballads balladic but to play them as jazz,' He succeeded; and so does the MJQ as to unit. In pointing out that the members of the quartet "go for themselves". more than before in this album, John did not mean to indicate that improvisation is a minor aspect of their other work. "The most important thing we're doing," he emphasized, "the bulk of what we play is improvisation. The rest is to give us a framework. And even those frames get moved or bent to fit what we're trying to project. A franc; may last for a while, and if it wears out, it has to be changed too. Anything wears out in time, and changes. All of what we do is relative, and we can be different at different minutes in different sets. in different nights." The essential importance of each individual in the MJQ is clear in John's discussion of how he writes for the group. "I have to listen end listen to Milt and Percy and Connie to absorb as much of them as I can so that I can write things that will be natural to the, that will be as close to their musical personalities as I can get. And that way too I can make is possible for them to best express themselves: musically in what I write and for me to express myself." Milt begins the ballad medley, recalling a visual-analytical description of his approach by Andrew Hodeir in the April, 1956, Jazz-Hot: Once he has chosen his theme, he respects its contours, an attitude which facilitates a generally happy choice of melodies by him. Knowing the quality of his sonority, he loves to let the long notes reverberate - reverberate purely - and even elongate them, it seems, to give them an increase of plasticity as Miles Davis does with obviously different means but an analogous intention. There's the impression that Milt is listening to himself play with an ear that is not at all complacent but that is, in a certain sense, charmed; and that he leaves certain sounds (whose resonance has not been entirely extinguished) only with regret and only under the imperative necessity of the melodic chain." Much has been written about Milt and his assured position as the most creative modern jazz vibist. The two qualities, in addition to his conception, that particularly individuate and fire his work are his "soul" (his ability to communicate open emotion directly); and his beat which is in itself an instantly clear definition of what it is to swing. The style of John Lewis as a soloist, as player of complementary lines to another protagonist, and in straight comping is most accurately described, I feel, as "classic" in the denotative sense of that term. I cite Webster's New International Dictionary (Unabridged): "Of or pertaining to a system regarded as embodying authoritative principles and methods; in accordance with a coherent system considered as having its parts perfectly co-ordinated to their purpose..." In all of John's works, written and pianistic, there is a clear depth of feeling for tradition, for the roots of the jazz language. In almost anything he plays, for example, one can hear the mark of the blues in John. Percy Heath has matured with constantly growing strength in the past three years. His tone has become fuller and firmer, his conception more consistent. He is in temperament and determination as excellent group player, and his willing to learn and grow as an individual through the learning and growth of the group. When I interviewed the then MJQ for a March, 1955 High Fidelity story, Percy said: "The music we're playing has become part of me, and it's such a challenge to try to say well what this music has to say that it'll be extremely gratifying if I'm ever able to fully accomplish that - to interpret our music fully." Percy has come a very long way in that time, and he was eloquent then. Connie Kay may well be the most underestimated member of the MJQ. This is partly due to the subtle usages of percussion in the MJQ's work and partly to Connie's own quietly observant, humorously reserved mien. He is a drummer of rare consistency of taste and with the further capacity to meet the extraordinary dynamics-demands of the unit. There are passages in some works like John Lewis' Variation No. 1 On "God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen" (in The Modern Jazz Quartet At Music Inn), in which Connie has to provide the kind of shading within shading that would have been the perfect accompaniment for the limitless numbers of angels who used to have to dance on that one medieval polemical pin. Withal, Connie swings - he pulsates with flowing surety - in whatever he does and through whatever manner of percussion instrument he strokes, attacks or otherwise animates. It is instructive to compare his version of the drum section of the La Ronde Suite with pervious interpretations by Kenny Clarke. I do not compare them qualitatively, because I feel each is meaningful in his own voice; but the comparison indicates how much room for individuality is left for the individual members of the MJQ. Of the rest of the music, there is little to say that the music does not itself make clear. I would note that the album contains two examples of jazz standards that have grown from within jazz, thereby adding to the body of relatively indigenous jazz material from Oh Didn't He Ramble to In A Mellotone To Godchild. The two here are Dizzy Gillespie's Night In Tunisia; and Milt Jackson's talk on and in the marrow of the blues, Bags' Groove, "Bags" being Milt Jackson's nom-de-jazz-guerre. Another point to be made about this album is that although it does not contain any of the quartet's longer works like Fontessa, it does set the problem again of where music like the MJQ's can find an optimum place to be played. Even though there is more "going for oneself in the LP, this is still music of unusual subtlety that requires an attentive audience, and audience sufficiently interested in listening to become active listeners. The most rewarding listening, after all, is that in which the bearer participates in the music, giving of himself emotionally and intellectually as he receives. On this subject, John Lewis has remarked: "People who play should think more about where they're playing. When you're playing in one kind of place, you have to do things that fit that place. Now, if you're in clubs, and feels better off in concerts, you should work in that direction as much as you can. There should be - but doesn't yet exist - something in between clubs and concerts, a place to play that isn't as formal as a concert, nor so cold (relatively speaking) but also where the bottles and glasses aren't tinkling either." "The quartet, for example, does much better in places where people can listen attentively. This is possible in some clubs, but not all. Musicians, to repeat, should start thinking in terms of what kind of settings they're best in. Some big bands might feel better in a theatre than a concert hall, because what they do, if well produced, can be turned into good theatre. Lionel Hampton, for one, shouldn't play concert halls; he'd probably, however, make exciting theatre. And then there are some people who are not theatrical at all, and wouldn't fit at all in theatres." John has obviously thought considerably about where the MJQ can best be heard and can best hear itself. Although the MJQ continues to play clubs, an increasing number of its dates are at colleges and concerts. In the fall of 1957, they begin a European tour that will set a valuable precedent for groups of their kind. Instead of touring for a short, intensive period as part of a "package" with other groups, the MJQ is going for itself. It participates first in the Donaueschingen Festival of Contemporary Music in Germany, October 19-25. The quartet then plays six weeks in Germany, Austria and Switzerland in college towns and small halls in larger cities. Four more weeks in France and Belgium are to follow plus possible dates in Scandinavia and an initial tour of Britain in January or February. In time, the MJQ may be the first modern jazz unit to create a continuing international circuit of which haste, night club and "packages" will be subsidiary and diminishing parts. The final Milt Jackson and Ray Brown track, the quartet's closing theme for the end of each set, is Baden-Baden. The Modern Jazz Quartet's selection of European place names for some of it titles (Concorde, Versailles) is a glancing indication, among other larger ones in his conversation, that John is perhaps the fullest example yet of international jazz musician who jazz roots are in America, but whose tastes, curiosities and life-experiences are not restricted to any one milieu. Jazz has obviously become an international language, and I expect that in the decades ahead, more and more of its practitioners will also become internationalized. It would not be the first time jazzmen have set an example in the breaking of artificial barriers. NAT HENTOFF