Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

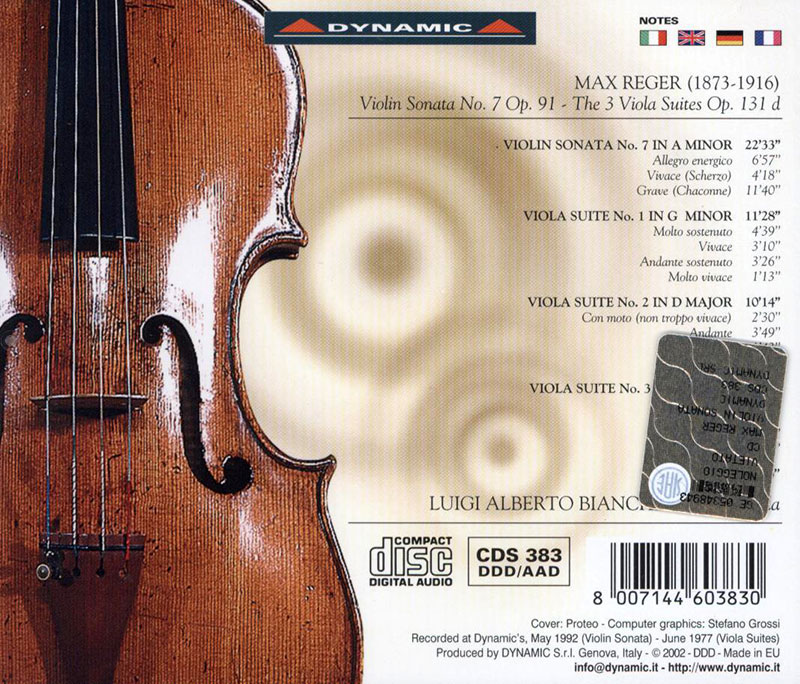

REGER, Luigi Alberto Bianchi

Violin Sonata No. 7 Op.91 / The 3 Viola Suites

- Luigi Alberto Bianchi - violin

- REGER

2010

“The variety of Reger's music could hardly be better suggested than by this pair of discs. Reger the wild modernist (by the standards of 1903) is vividly before us in the headlong, turbulent, disconcertingly chromatic outer movements of the Op 72 Sonata, with their huge variety of moods and frequent abrupt changes of direction. But the Little Sonata of only six years later is almost classical by comparison; it's much more direct, economically worked and tightly argued. And in all the unaccompanied music in Luigi Alberto Bianchi's recital we meet Reger paying sincere and often touching homage to Bach.

Bianchi's disc is beautiful but poignant. The three Suites for viola were recorded in 1977 on a large and sumptuously rich-toned viola by the brothers Amati, the Medicea. It was stolen three years later; Bianchi began playing the violin instead and eventually acquired a fine Stradivari, the Colossus, upon which in 1992 he recorded the unaccompanied Violin Sonata. That too was stolen six years thereafter, and apart from the interest of the music and the eloquence of the playing this disc has the sad value of being perhaps the last that we shall hear of two exceptional instruments.

Reger's love for the violin is as evident in the Op 91 Sonata as is his reverence for Bach. All the movements are like Bach in late-Romantic dress, and the finale is a magnificent chaconne.

Ulf Wallin plays with a slightly narrower tone than Bianchi, which works well in the tumultuous gestures of Op 72. But he and Roland Pöntinen are just as alive to Reger's moments of withdrawn pensiveness and long lines, which need care if their chromatic shifts aren't to make them seem diffuse; they never do here. The recordings are excellent.

Years ago the merest mention of Shostakovich's First Violin Concerto brought just two key stylistic templates to mind: David Oistrakh and, a little later, Leonid Kogan. Oistrakh in particular had fashioned such a warm and intimate reading of the piece that it became almost impossible to imagine a credible alternative. And yet the passing years have brought many, not least Perlman, Mullova, Vengerov and Chang, to name some of the best.

Hilary Hahn is certainly in their league, though different again. She's a lean, athletic player, utterly still at the muted centre of the Concerto's first movement, and with elfin agility in the Scherzo. Hahn is to be preferred, primarily because her sweetness-and-steel tone, with its expressive but narrow vibrato, lends a fresh perspective to the work but also because of Marek Janowski's fine conducting.

Some might find Hahn's approach a trifle cool, especially in the cadenza. Hahn is a very clean player, colour-conscious but never dangerous in the manner of her most rival, Ilya Gringolts, though she does engage in some active dialogue with individual soloists. Only the finale seems a little short on what one might call ambiguous sparks – where sudden ignition could be taken either as celebration or protest – but as fiddle-playing per se, it really does cut the mustard. Among digital rivals Vengerov and Khachatryan are still tops, though as Hahn is nearer than they are to the honeyed tones of pre-war players some collectors might favour her on that count alone.

As to the coupling, Hahn gives a swift, resilient, bright-toned reading, tender-hearted in the Andante and very fast in the finale. Too fast perhaps for true composure. Still, it's a fine display, and this is a thoroughly fine disc, confirming Hilary Hahn as among the most gifted and individual players on the concert circuit.”