Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

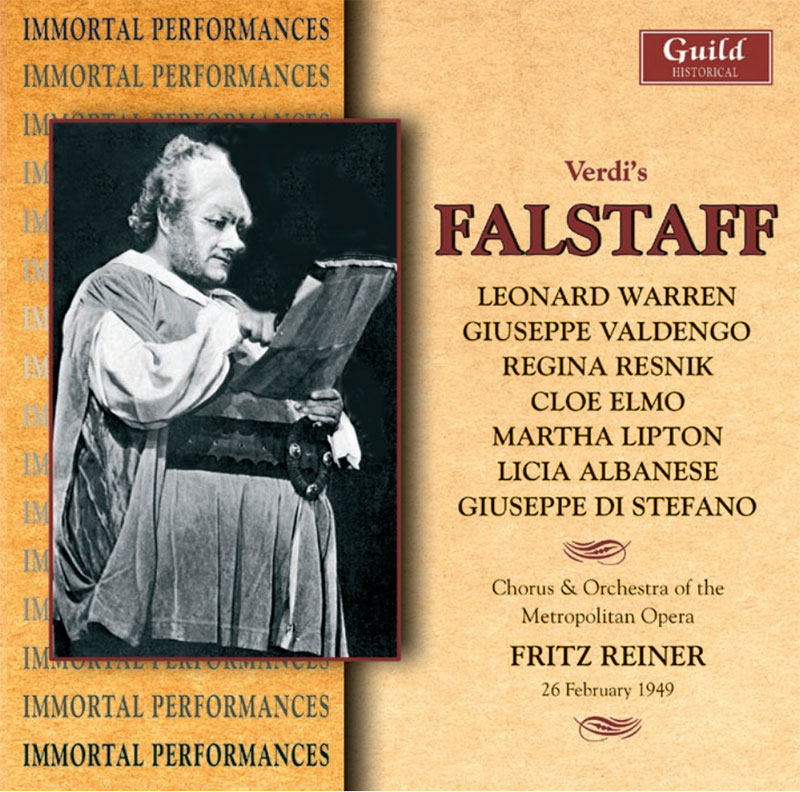

VERDI, Leonard Warren, Giuseppe Valdengo, Giuseppe di Stefano, Fritz Reiner, The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus

Falstaff - 1945

- CD 2 Track 11 - Ehi! Taverniere! (Falstaff — Leonard Warren) >>> Posłuchaj fragmentu <<<

- CD 2 Track 17 - Dal labbro il canto estasiato vola (Fenton — Giuseppe di Stefano)

- Leonard Warren - baritone

- Giuseppe Valdengo - baritone

- Giuseppe di Stefano - tenor

- Fritz Reiner - conductor

- The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus - orchestra

- VERDI

Falstaff holds the distinction of not only being Verdi’s final opera but also his only successful opera buffa; his first, written at the age of 27, was a total failure. Verdi and his librettist, Boito, at first kept the composition of Falstaff in complete secrecy, only revealing it publicly after the completion of the first act. This work displays Verdi’s true versatility: the soaring melodrama of his previous works is gone, replaced by music ingeniously constructed to display charm, wit, and light-heartedness. This particular recording is notable for several reasons. First, the recording is not just of the opera; instead, it is a recording of the Met broadcast of February 26, 1949 and includes commentary by Milton Cross. As the Richard Caniell’s liner notes explain, this production was one of the huge hits of the 1948-49 season, due, in part, to the illustrious conductor, Fritz Reiner, as well as to the work’s rarity before 1949 - at least at the Met. Leonard Warren, Giuseppe Di Stefano and Licia Albanese stand to this day as among the best voices of the 20th century. These "time capsule" qualities alone make this recording worth owning. The recording holds some incredible singing and playing. The American baritone, Leonard Warren, gives a great performance. His rich, dark timbre is perfect for the bamboozling, obese Falstaff. As usual, his upper register is exciting — this voice is rare in its naturally dark, yet resonant timbre in combination with a virtually unlimited top. Di Stefano sings beautifully. Once again, the listener is rewarded with a truly exceptional voice: full, lyrical, completely focused, and produced with extreme ease. He and Licia Albanese make a remarkable combination. The young, clandestine lovers sing sensitively together, and their intermittent bouts of flirting are refreshing, passionate and quite hilarious. Other members of the cast are equally adroit in their singing and characterization. Giuseppe Valdengo as Ford works well with Warren, as their baritone voices are strikingly different. Alessio de Paolis and Lorenzo Alvary as Falstaff’s henchmen sing with incredible spirit and hilarious inflection. Reiner’s conception of the piece is, at times, a bit haphazard. He allows the orchestra to peak too often and too regularly rather than projecting the dramatic action in large-scale phrases. The result is too much weight and importance assigned to too many different occasions. We must not be surprised at the fallibility of the sound given the historical nature of this recording of a live broadcast. An ambient hiss is present more often than it isn’t, and in many places, the orchestra is somewhat obscured by a sort of haze. For these reasons, it is difficult to make many specific comments in regard to the performance. However, there is no doubt that this recording is top notch. The questionable sound quality prevents it from being one’s primary recording of this work; however, it offers much insight not only into Verdi’s final opera but also into the operatic achievements of a previous generation. Jonathan Rohr