Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

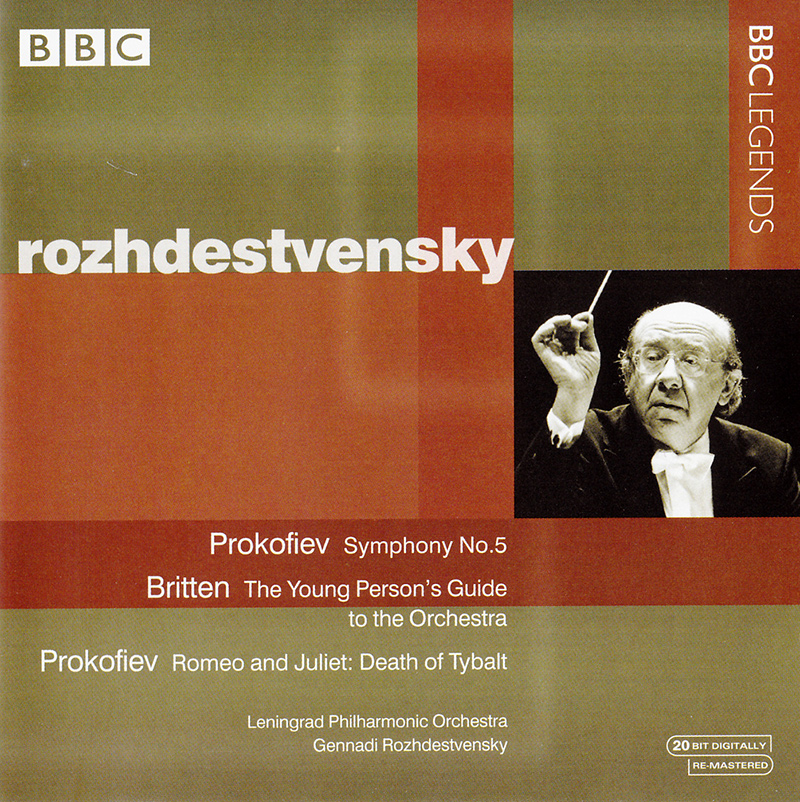

PROKOFIEV, BRITTEN, Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, Gennady Rozhdestvensky

Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major / The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra / Death of Tybalt From Romeo and Juliet Suite

- Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra - orchestra

- Gennady Rozhdestvensky - conductor

- PROKOFIEV

- BRITTEN

None of these performances equals or bests their recorded predecessors, so if you're shopping for single versions of each, continue elsewhere. But the Prokofiev Fifth captures one of those moments when an insightful but workaday performance, out of nowhere, suddenly becomes exalted - what athletes refer to as "getting in the Zone." It may be difficult, especially for infrequent concertgoers, to understand how this can happen (or, conversely, why it isn't an everyday occurrence!). But veteran performers can attest to those experiences that transcend the routines and limits of quotidian music-making - it's happened to me on the podium exactly twice. The first movement's forthright address, with the tempo edging faster as early as 1:36, may represent, not a broadly "Russian" tradition, but one peculiar to Leningrad/St. Petersburg: Jansons's St. Petersburg concert recording (Chandos) is similarly brisk and taut, but Oistrakh and Simonov's Moscow-based recordings play the music more broadly, in the customary Western style. Listeners accustomed to more weight and deliberation, to a more searching manner, may take issue with such a no-nonsense approach. But it has its benefits, disposing of the perpetual question of whether or not to speed up at Prokofiev's animato marking - the pace having become sufficiently "animated" as to require no further adjustment - and realizing a certain epic sweep in the development, as the brasses call across the orchestra with their long-breathed motifs. Since the playing is good but not great - the violin tone tends to harden under pressure, or to go glassy at the top, and the trumpets' heavy vibrato is distracting - this plausible and musical rendition hardly seems one for the ages. At the scherzo's start, Rozhdestvensky takes pains to give the chugging accompaniment an undulating shape that brings out the music's long line; but the figures settle into a more routine motor impulse as the movement progresses. The conductor's markedly slower pace for the "B" section, however - Ormandy (Sony, RCA), among others, used to take it this way - underlines its gentle piquancy and its lyricism at once. The first statement of the Adagio theme is tentative, but the strings' immediate repeat is more confident and full-throated. The second theme, at 3:31, pushes forward impulsively in the manner of the opening movement, and the subsequent series of contrasting episodes, flowing rather than starkly dramatic, goes well enough. But, at 7:35, after the big outburst, the magic happens: the violins intone the return of the opening theme with a breathtaking hush, and over the next four minutes the movement spins to a close with unerring concentration. The musicians stay "in the Zone" for the Finale. The strings at 0:24 vibrantly recall the first movement's principal theme. The horns' light, crisp accenting of their ostinato lends the movement an easy propulsion, over which the clarinet and then the violins project their running theme with relish. The 'cellos make deep, rich sounds in their brief moment in the sun at 6:09, and the violins' numerous "upbeat" runs (the first is at 7:10) sound warm and assured, without smearing or blurring. All in all, it's a fulfilling end to a performance whose beginning seemed to promise less. The companion pieces, dating from eleven years earlier and recorded monaurally, find conductor and orchestra at a less assured stage of their collaboration - and in the Britten, dealing, I suspect, with relatively unfamiliar territory as well. The statement of the Purcell theme is suitably ceremonial, marred by moments of slurry violin playing. Among the individual variations, the best are those that allow for a measure of virtuoso panache: those featuring the dazzling passagework of the duetting flutes, for example, or the galloping trumpets and snare drum. Other episodes, such as the clarinets', even when musically sympathetic, feel somehow less idiomatic. The closing fugue, taken at a breakneck pace, suffers a few brief ensemble lapses, though, judging by the applause, it made a thrilling impression in the hall. The encore performance of The Death of Tybalt is no better or worse than numerous other renditions. If nothing else, the symphony reminds us record mavens of an important difference between a concert performance and a studio recording: in concert, wonderful things can happen, sometimes when everyone - including the performers - least expects it. Stephen Francis Vasta