Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

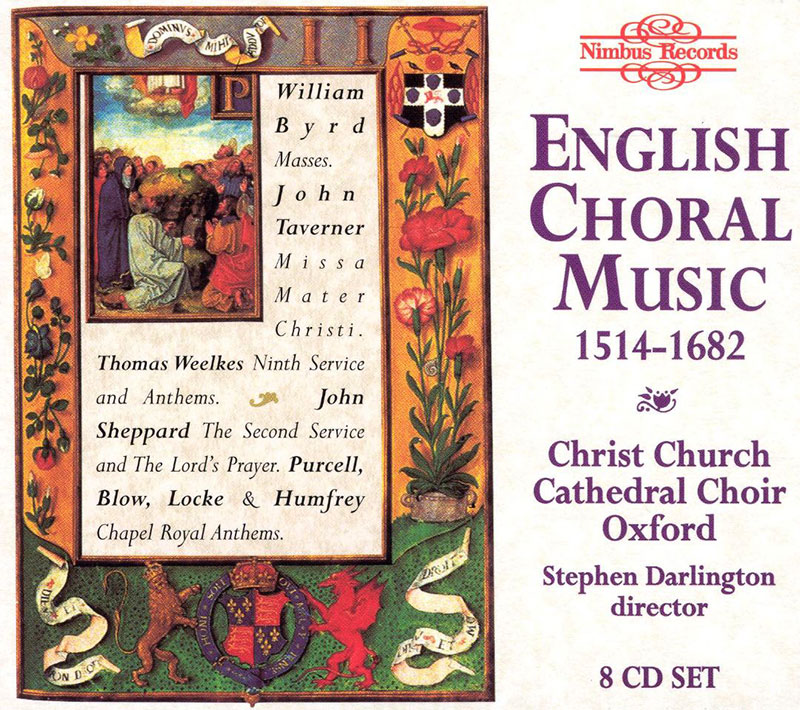

Christ Church Cathedral Choir, Oxford, Stephen Darlington

English Choral Music 1514-1682

- Christ Church Cathedral Choir, Oxford - choir

- Stephen Darlington - conductor

NI 1762 " Evensong was begun; the Dean and canons were there in their grey amices; they were almost at 'Magnificat' before I came thither. I stood at the choir door, and heard Master Taverner play, and others of the chapel there sing, with and among whom I myself was wont to sing also; but now my singing and music were turned into sighing and musing." When Anthony Dabaler, a scholar of St Alban Hall, made this testimony after his visit to 'Frideswide's Church' he must have been impressed by the building progress on Cardinal Thomas Wolsey's new Oxford College. The year was 1528, and only the Great Hall and kitchens of Cardinal College were completed on the site of the ancient monastery of St. Frideswide. Three western bays of the priory church (where the daily services were temporarily held) were demolished in order to accommodate Wolsey's massive quadrangle, which was to be closed at its north end by a new chapel to rival that of King's College, Cambridge. However, Wolsey fell from King Henry VIII's favour before building work was ever completed and was forced to surrender his Oxford college to the crown. In 1548, Henry refound the college and the episcopal see of Oxford was translated from Osney to his new collegiate foundation, thus creating the unique institution of college and cathedral in 'Christ Church'. Wolsey's college at Oxford was so short-lived that few events are recorded of its history. One biographer commented that "if all the rest [of the college] had bene fynished, to that determinate end as it was begonne, it myght well have excelled not only all colleages of students, but also palaices of Princes". However, whilst Cardinal College existed it thrived both intellectually and culturally, attracting the most learned minds of the time. Wolsey laid the task of appointing a choirmaster to John Longland (1473-1547), Bishop of Lincoln, to which diocese Oxford then belonged. Longland's first choice for the position was Hugh Aston (c. 1485-71 558) who declined the offer on the grounds of already having a secure and well-paid post at Newark College, Leicester. His second choice was John Taverner, of Boston, who had also initially declined the offer owing to the prospect of a good marriage; however, by October 1526, when Cardinal College formally opened, Taverner had already begun his duties as Wolsey's Informator choristarum. With a provision for twelve layclerks and sixteen choristers (as is still the case for the present choir), a very high standard of music-making was attained at Cardinal College. The liturgical day was framed around the seven canonical hours, collectively known as Divine Office (matins, lauds, prime, terce, sext, none, vespers - also known then as evensong - and compline). With the canonical hours came also the daily Mass celebrations, of which there were three types: the Mass of the day, the 'Morrow' Mass, and the Votive Mass of the Virgin, or 'Lady Mass'. Lady Mass was usually celebrated privately, but in some English monastic and collegiate foundations it was performed by a part of the community or a small group of singers, normally in a Lady chapel. Taverner's Kyrie le Roy and Alleluya almost certainly would have been sung at such devotions in Cardinal College. Thomas Weelkes (c. 1576-1 623) composed most of his church music during the first two decades of the seventeenth century. This coincided with the decline in his professional career and private life and he ended his days in disgrace, dismissed from his post as organist at Chichester on the grounds of his being a common drunkard and a notorious swearer and blasphemer. The music recorded here falls roughly into two sequences, one representing works of a general nature composed for no specific or known destination, the other, pieces that Weelkes probably wrote with courtly circles in mind. Modern as his madrigalisms may be by the standards of English church music of the day, at heart his music is embedded in tradition and nourished by a strong sense of heritage. John Taverner (c. 1490-1545) became the first instructor of the choristers of the choir of Christ Church College in 1526. His time there was brief due to the fall from grace of cardinal Wolsey, the founder of the college and by April 1530 he left and became a lay clerk to the choir at St. Botolph's church, Boston, Lincolnshire. However most of his music was composed in the decade 1520-1530 during the height of Wolsey's power and his most substantial works are those in the three traditional forms of large-scale writing: the mass. Magnificat and votive antiphon. William Byrd (1543-1623) was a modernist in the greatest sense of the term whilst simultaneously clinging to antiquated religious beliefs. Unlike Tallis before him and Morley after, Byrd had no significant contemporary English rivals in musical composi- tion, and thus the music which flowed from his pen was fresh in form and original in conception. Yet, his musical genius was continuously haunted by his sympathies for the demised Catholic Church in England, his involvement with which is well documented. Although a master, and indeed innovator of most musical genres practiced by his gen- eration, the greatness of his musical expression is most aptly witnessed in those Latin compositions of the last thirty years of his long life, namely the three Masses and a vast number of Latin motets. John Sheppard (c. 1515-1559) in a lifetime extending to fewer than fifty years witnessed both the apogee and almost the nadir of the fortunes of choral endeavour within the English church. During his career as one of the lay Gentlemen at the Chapel Royal he served the Protestant Edward VI, the Catholic Mary I and her Protestant successor Elizabeth I. As a result he was composing religious music within abruptly changing reli- gious and political environments, factors which inevitably varied the nature of his and his contemporary's output. The compositions of Locke, Humfrey, Blow and Purcell are the cream of Restoration church music, and all were part of the tight circle of Court composers associated with the Chapel Royal. The Anthem is the dominant form in these composers' output and the sheer quantity written reflects the day-to-day needs of the country's Chapels and Cathedrals.