Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

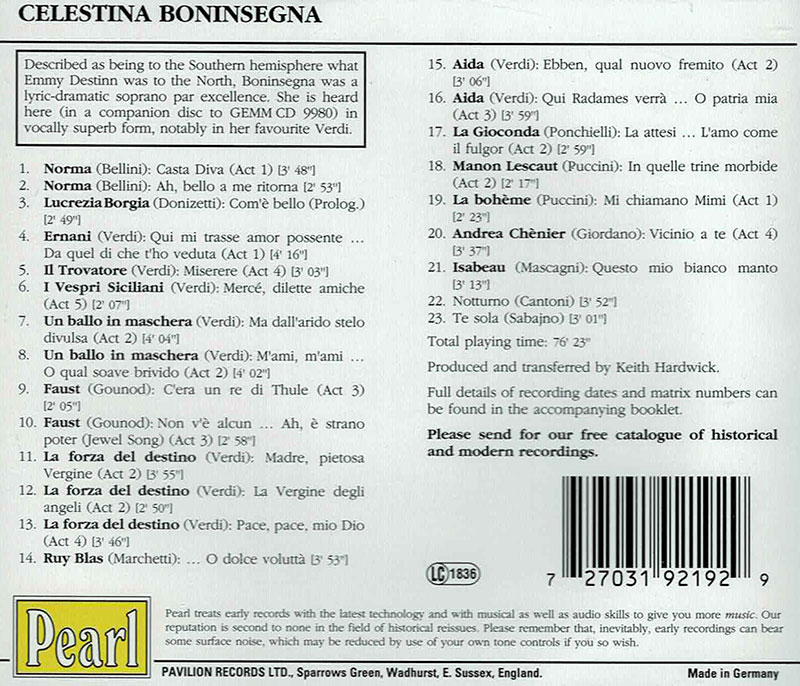

BELLINI, VERDI, MARCHETTI, PONCHIELLI, Celestina Boninsegna

Celestina Boninsegna - Volume II

- 1. Norma: Keusche Göttin

- Bellini

- 2. Norma: O kehre zurück, du Teurer

- Bellini

- 3. Lucrezia Borgia

- Donizetti

- Com'e bello (Prolog)

- 3. Ernani: Seit dem Tag, da ich dich gesehen

- Verdi

- 4. Der Troubadour: Hab Erbarmen, o Herr

- Verdi

- 5. Die sizilianische Vesper: Wie soll ich euch, ihr Treuen danken

- Verdi

- 6. Ein Maskenball: Wenn das Kraut, wie die Seherin kündet

- Verdi

- 7. Ein Maskenball: M'ami, m'ami

- Verdi

- 8. Es war ein König in Thule

- 9. Margarethe: Nur große, Herrn...Ha, welch ein Glück

- Gounod

- 10. Die Macht des Schicksals: Mutter der reinsten Gnaden du

- Verdi

- 11. Die Macht des Schicksals: Die Himmelsjungfrau gnadenvoll

- Verdi

- 12. Die Macht des Schicksals: Frieden, Frieden

- Verdi

- 13. Ruy Blas: O dolce volutta

- Marchetti

- 14. Aida: Ebben, qual nuovo fremito

- Verdi

- 15. Aida: Bald kommt Radames...O Vaterland

- Verdi

- 16. La Gioconda: L'amo come il fulgor del creato

- Ponchielli

- 17. Manon Lescaut: Ach, in den kalten Spitzen hier

- Puccini

- 18. La Boheme: Man nennt mich jetzt Mimi

- Puccini

- 19. Andre Chenier: Dann findet meine rastlose Seele Frieden

- Giordano

- 20. Isabeau: Questo mio vivere un po fuori

- Mascagni

- Celestina Boninsegna - soprano

- BELLINI

- VERDI

- PONCHIELLI

- MARCHETTI

In the happy hunting-days of what can perhaps without too much offence be called'the old 78 collectors', records by Boninsegna were high on the list of desirables. With a single exception, they had fallen out of regular circulation by the 1930s and by report they were outstandingly good. Moreover, their merit lay not only in the beauty of the voice and the excellence of its usage, but also in their presentation of a soprano who, although pre-electrically recorded, did not sound preelectric. Accordingly, large prices (all of Ł3 or Ł4) were asked in the second-hand lists, and within a few years, say by 1950, they had doubled. The single exception, which remained available in the His Master's Voice Historic Catalogue till wartime deletions gradually stripped it bare, was a doublesided twelve-inch record of two arias, 'Madre, pietosa vergine' and 'Pace, pace, mio Dio' from La forza del destino, recorded in 1907 and included in the companion volume to this one, GEMM CD 9980. It was introduced in the catalogue by a brief biographical note which described Boninsegna as having become "prima donna at La Scala, Milan, in 1905"; it also claimed that she had sung in "the most important opera houses on the Continent" as well as in London, New York and Buenos Aires. London we knew about. P.G. Hurst, a formidable authority among British collectors, had told us of her appearances at Covent Garden in the Collectors' Comer articles he wrote for The Gramophone, later incorporated into his books 'The Golden Age Recorded' and 'The Age of Jean de Reszke'. In the latter we read: Following the successful summer season (of 1904), the San Carlo Opera Company of Naples gave a short season in October and November, which continued to add to the new talent for which this year was notable. Perhaps the first place among these new artists should be awarded to Mme. Boninsegna, a dramatic soprano of quite unusual gifts, whose uncommon type of voice combined the soprano with the contralto, not merely in range but in quality. Without a doubt, Boninsegna was the finest Aida I have heard, and I heard her twice in the role; naturally she was also the perfect Amelia in the Ballo. Her success was very fully recognised and acknowledged, but for one reason or another she never reappeared in London; but she left a legacy of superb gramophone records made at that time and later, which today are much required by collectors. That she never reappeared is not quite true, for she was back in 1905, adding Il trovatore to the operas she sang over here, but there was nothing after that and she never featured in the much more prestigious 'Grand' summer seasons. 1958, the year in which Hurst's 'Age of de Reszke' was published, has a special place in the posthumous career of our singer. It initiated what has come to be known as 'the Boninsegna enigma'. To follow this, we have to go (as for so much else) to the files of the specialist magazine The Record Collector, and as not all readers will have back-numbers it may be as well to summarise. Two regular contributors, Clifford Williams and J.B. Richards, had been working for some years on material concerning Boninsegna's records and career. Starting from the background outlined above, they had managed to hear most, though by no means all, the records and were able to compile a reliable discography. Like other collectors, they had been thrilled by the voice and impressed by testimonials such as those of Hurst and Fred Gaisberg, HMV's famous producer who had himself recorded Boninsegna and who, in his book, described her as being to the Southern hemisphere what Emmy Destinn was to the North, the lyric dramatic soprano par excellence. A surprise and disappointment encountered right at the start of their researches was the discovery that, so far from having been "prima donna at La Scala" in the expected sense of a long-established career in the house, she had sung there in one season only (that of 1905) and in the single role of Aida, in which she was replaced at some point during the course of the run by Giannina Russ. Nor as far as they could ascertain had she ever been a member of the San Carlo Company (under whose auspices she appeared in London). Her American career proved similarly limited: her South American appearances were confined largely to houses of secondary importance and her short time with the Metropolitan in New York (December 1906 to February 1907) is described as 'disastrous'. They could find nothing definite about her career after 1920 and concluded that in all probability she had retired at the age of 43. Canvassing opinions from other sources, the authors of this Record Collector study found several correspondents willing to pontificate. H. Hugh Harvey wrote that he found it impossible to imagine that anyone could have surpassed Destinn as Aida (that was by way of anointing Hurst with cold water), and Roberto Bauer, another almost legendary authority among collectors, held that "nobody in Italy ever regarded Boninsegna as a 'great' singer nor as a first-class singer". This drew P.G.H. himself into the dispute, with a letter in which he pointed out that by their own admission neither Harvey nor Bauer (and there were others) had heard Boninsegna 'in the flesh' and that he had: I heard her in person before I heard her records, and it was the deep impression that she made upon me that led me so much to enjoy hearing her records a year later. Her acting (a point which had been criticised by several writers) was vivid and dramatic – I particularly remember the force of her scene with Amonasro, and the way in which she presented every aspect of this varied role. She was capable of intense emotion and gentle pathos, and I can still hear her lovely voice soaring with effortless beauty. Support then came from Italy. Rodolfo Celletti wrote to confirm the date of her debut (1897, at Bari in Faust), but he also reported a conversation with Eugenio Gara, "Italy's leading music critic in the field of vocalism", Gara, he said, had told him "that he had heard Boninsegna on a number of occasions and that, especially in Il trovatore, he considered her to be among the greatest singers of the period - an opinion that demands the highest respect in view of Gara's eminence as a critic". Another correspondent, C.G.S. de Villiers, wrote to describe a meeting with Boninsegna following his discovery in 1934 that she was still to be found entered in the Milan telephone book. "A tall, well-covered woman with snow-white hair", she was happy to see him having been assured that he was not a reporter: she also sang to him, on his request, Aida's 'O patria mia'. "Not Battistini's Rigoletto (he wrote), not Berta Morina's Isolde, not GutheilSchoder's Salome have left a more indelible impression on me than Boninsegna's singing in her music room in the drab northern Italian City". The final instalment in this sequence of articles and letters, all giving the subject the best airing it has ever had, came in the form of a survey of comments in the American press: 'Celestina Boninsegna in the United States: Contemporary Critics Speak' by W.R. Moran. This, for a start, established the New York debut as having been far from 'disastrous': "Mme. Boninsegna disclosed powers that will make her a welcome and important addition to the company" (New York Times): "In her, Mr. Conried has one of the season's discoveries. Step by step the audience warmed to her singing despite the terrors of her makeup" (New York American). A mutilated and unidentified clipping spoke of her second appearance as better than her first: "There was more than routine excellence in what she did". On her return to the States at the Boston Opera House in 1909 the Boston American's opera critic, C.H. Meltzer, wrote: "Her voice was then (four years ago) as vibrant, fresh and pure as it appeared last night. But for reasons which have never been explained - they may have had to do with the peculiarities of her make-up (she has since discarded them) or with the intrigues of her long-established rivals - she failed to content the rather unreasonable New Yorkers and went back to Italy". She did so again, after a performance of Tosca, also at Boston, in which the same paper (and probably the same critic) claimed that "Celestina Boninsegna revealed herself as a Tosca compared to whom Geraldine Farrar's is a giggly school girl ... The second act revealed a tragedy queen. All the emotions seemed at the command of the singer. Her expressive face spoke fear,.grief, shame and agony ... She was vocally superb in this act." There were criticisms too, numerous and serious enough to make it clear that, however magnificent Boninsegna could be when on form, she was also a very variable performer. Hence the enigma, for on records she is remarkably consistent. In any event, enough has probably been said about the past. Records belong to the present and, as to them and their merits, it is for the listener to decide. JOHN STEANE