Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

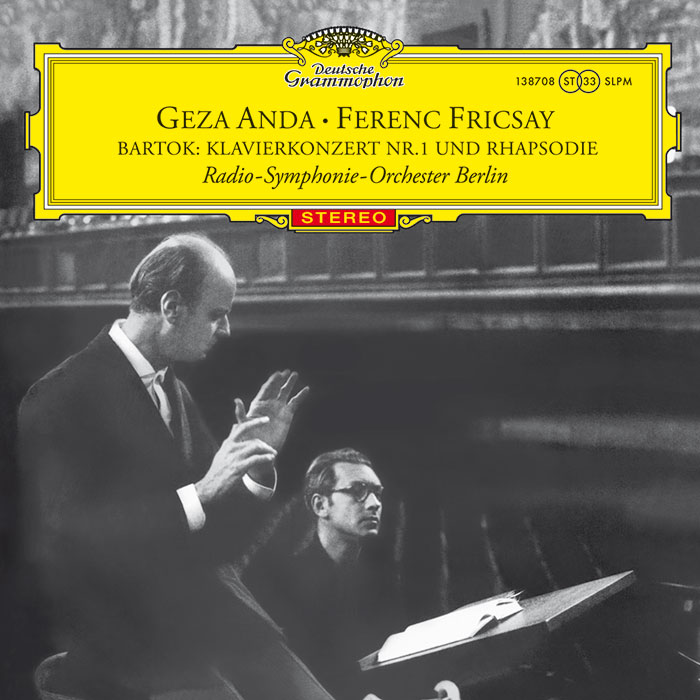

BARTOK, Geza Anda, Ferenc Fricsay, Radio-Smphonie-Orchester Berlin

Piano Concerto No. 1

Between Bartók?s Rhapsody for Piano and his First Piano Concerto lie 22 years of development, a struggle to find subject matter, form and his own musical language. While the Rhapsody from 1904 is dominated by a late-Romantic tone, which delights in a free, craggy and capricious feast of affable harmonies, the Piano Concerto reflects contemplation and a delving into the formal strictness of the classical three-movement concerto form. Rather less concerto-like and unconventional is, however, the use of the piano as a percussion instrument, which after just a few bars on the winds, hammers out an unrelenting staccato against the harsh and dissonant orchestra. In the slow movement too the piano is predominantly employed as a percussion instrument that, like the pendulum of a clock, rhythmically bulldozes on against the cheerless, bleak winds. Wild emotion predominates in the Finale. Stormy, insistent figures in the piano are answered by the orchestra with animated blows, but the quick flashes of melodies cannot establish themselves and are slashed to pieces as if caught in a storm. This uncompromising severity presents an enormous challenge that is mastered with aplomb by Géza Anda and the RSO Berlin under Ferenc Fricsay. Bartók?s musical language is milder and more accessible in his Second and Third Piano Concertos.