Logowanie

Dlaczego wszystkjie inne nie brzmią tak jak te?

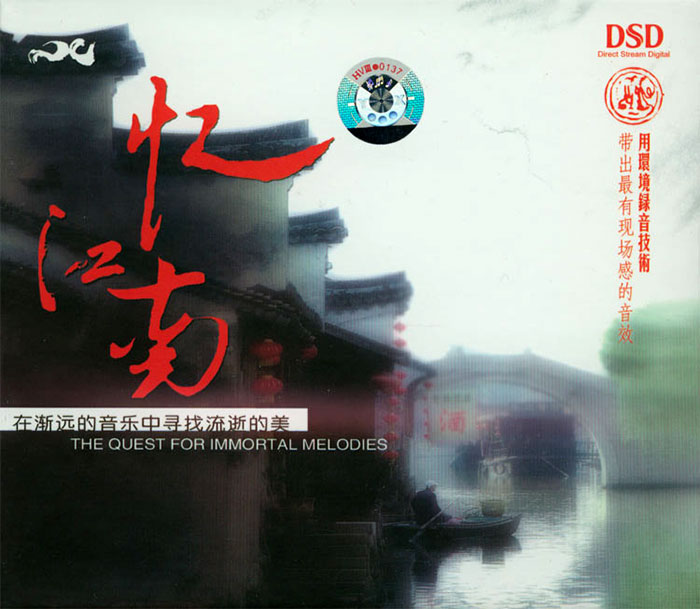

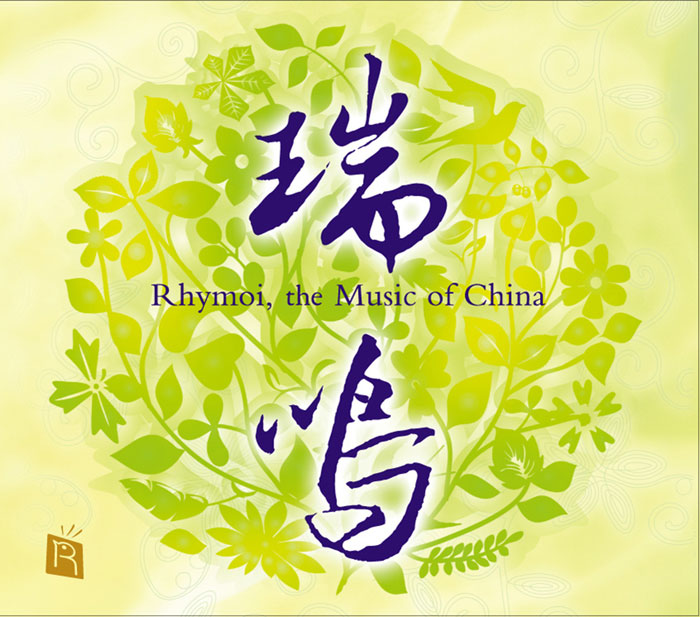

Chai Lang, Fan Tao, Broadcasting Chinese Orchestra

Illusive Butterfly

Butterly - motyl - to sekret i tajemnica muzyki chińskiej.

Brzmią jak sen na jawie

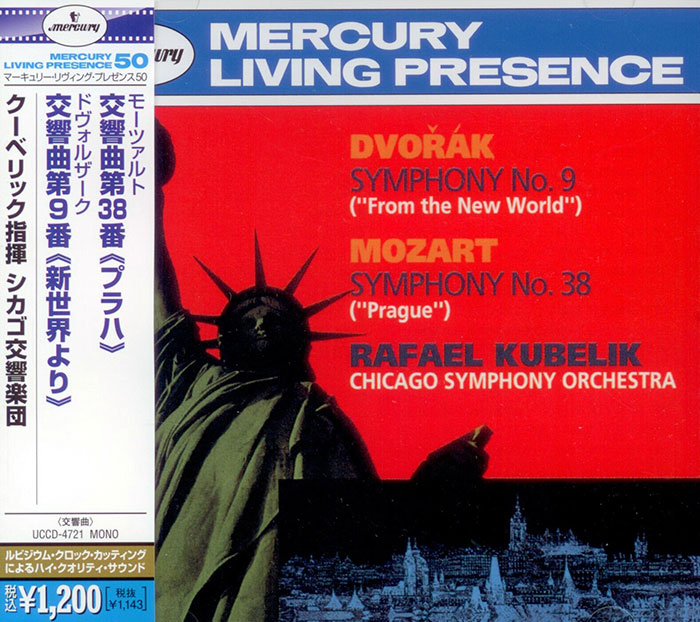

KHACHATURIAN, SHOSTAKOVICH, Antal Dorati, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, The London Symphony Orchestra

Gayne / Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47

Stanisław Skrowaczewski,

Winylowy niezbędnik

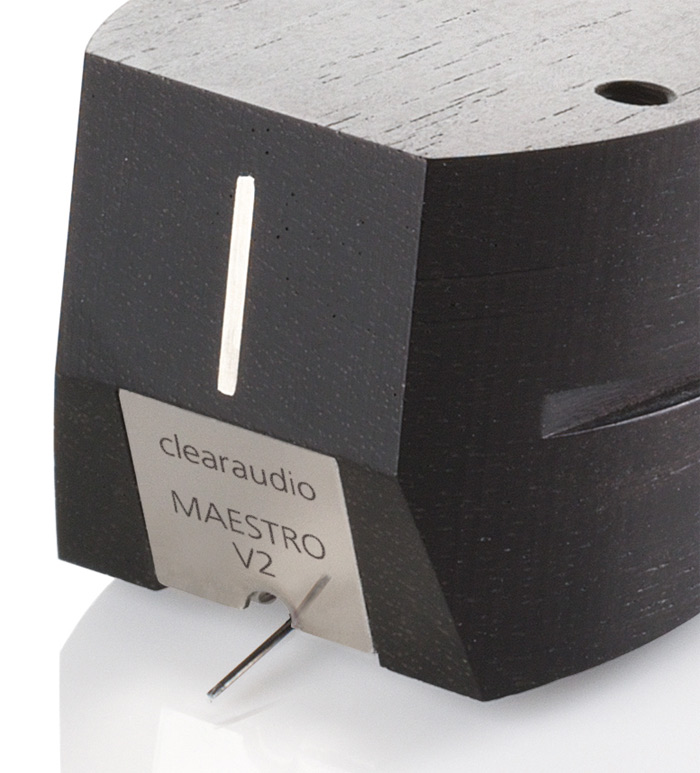

ClearAudio

Cartridge Alignment Gauge - uniwersalny przyrząd do ustawiania geometrii wkładki i ramienia

Jedyny na rynku, tak wszechstronny i właściwy do każdego typu gramofonu!

ClearAudio

Harmo-nicer - nie tylko mata gramofonowa

Najlepsze rozwiązania leżą tuż obok

IDEALNA MATA ANTYPOŚLIZGOWA I ANTYWIBRACYJNA.

Osobowości

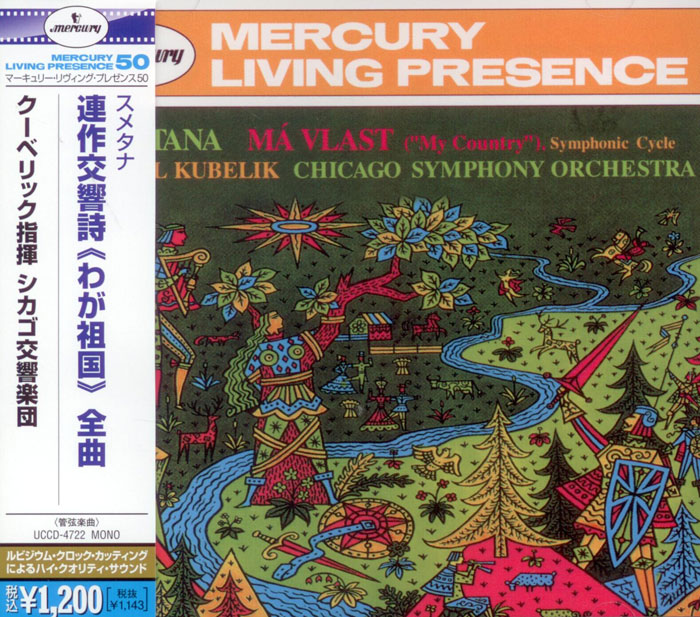

SKROWACZEWSKI, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Minnesota Orchestra

Concerto Nicolo for piano left hand and orchestra

WORLD PREMIERE!

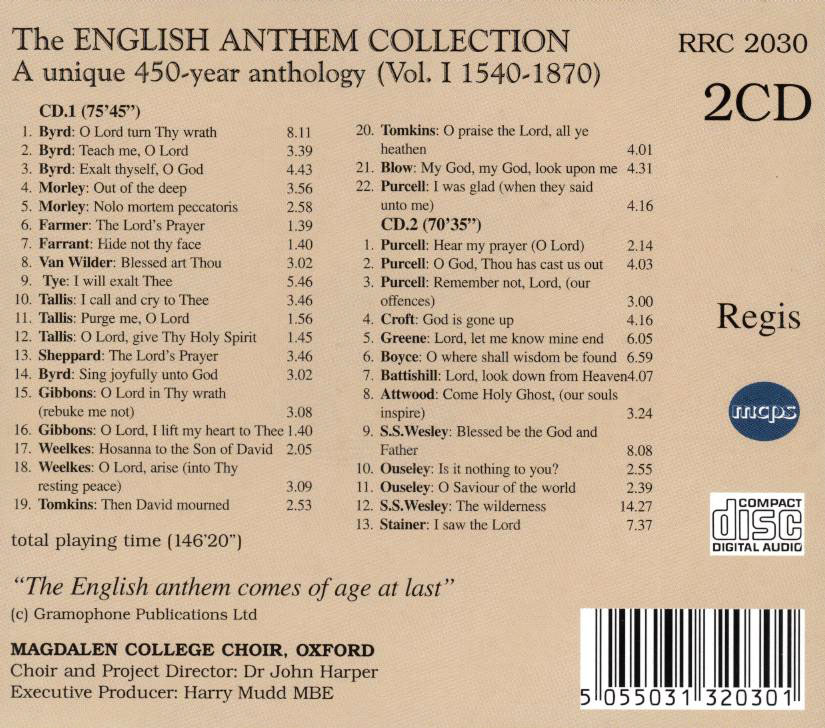

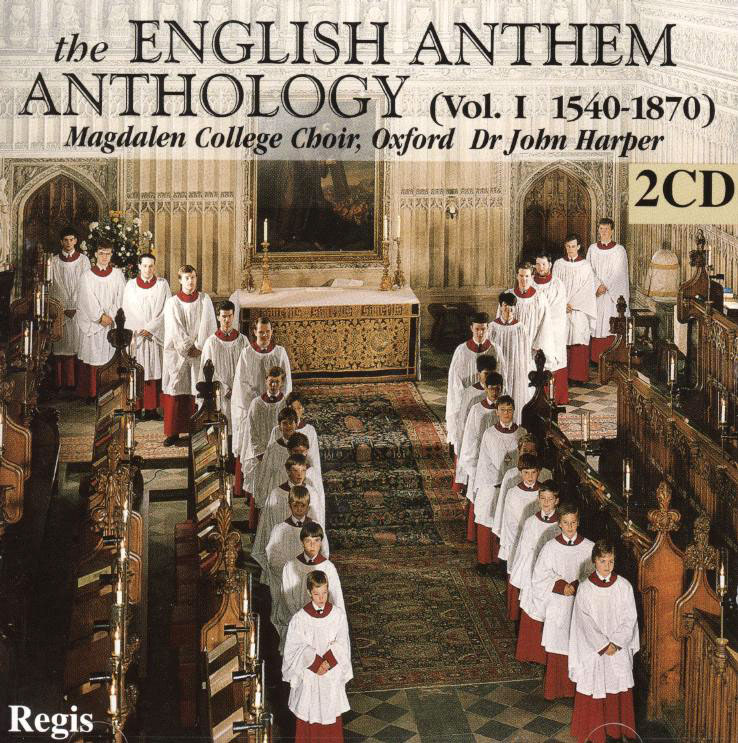

BYRD, TALLIS, GIBBOONS, MORLEY, Choir of Magdalen College Oxford, John Harper

Anthology of English Anthems - vol. 1 - 1540 - 1870

- CD.I (75'45")

- 1. Byrd: O Lord turn Thy wrath 8.11

- 2. Byrd: Teach me, O Lord 3.39

- 3. Byrd: Exalt thyself, O God 4.43

- 4. Morley: Out of the deep 3.56

- 5. Morley: Nolo mortem peccatoris 2.58

- 6. Farmer: The Lord's Prayer 1.39

- 7. Farrant: Hide not thy face 1.40

- 8. Van Wilder: Blessed art Thou 3.02

- 9. Tye: I will exalt Thee 5.46

- 10. Tallis: I call and cry to Thee 3.46

- 11. Tallis: Purge me, O Lord 1.56

- 12. Tallis: O Lord, give Thy Holy Spirit 1.45

- 13. Sheppard: The Lord's Prayer 3.46

- 14. Byrd: Sing joyfully unto God 3.02

- 15. Gibbons: O Lord in Thy wrath (rebuke me not) 3.08

- 16. Gibbons: O Lord, I lift my heart to Thee 1.40

- 17. Weelkes: Hosanna to the Son of David 2.05

- 18. Weelkes: O Lord, arise (into Thy resting peace) 3.09

- 19. Tomkins: Then David mourned 2.53

- 20. Tomkins: O praise the Lord, all ye heathen 4.01

- 21. Blow: My God, my God, look upon me 4.31

- 22. Purcell: I was glad (when they said unto me) 4.16

- CD.2 (70'35")

- 1. Purcell: Hear my prayer (O Lord) 2.14

- 2. Purcell: O God, Thou has cast us out 4.03

- 3. Purcell: Remember not, Lord, (our offences) 3.00

- 4. Croft: God is gone up 4.16

- 5. Greene: Lord, let me know mine end 6.05

- 6. Boyce: O where shall wisdom be found 6.59

- 7. Battishill: Lord, look down from Heaven 4.07

- 8. Attwood: Come Holy Ghost, (our souls inspire) 3.24

- 9. S.S.Wesley: Blessed be the God and Father 8.08

- 10. Ouseley: Is it nothing to you? 2.55

- 11. Ouseley: O Saviour of the world 2.39

- 12. S.S.Wesley: The wilderness 14.27

- 13. Stainer: I saw the Lord 7.37

- Choir of Magdalen College Oxford - choir

- John Harper - conductor

- BYRD

- TALLIS

- GIBBOONS

- MORLEY

To ascribe the rise of the English anthem to the political and religious changes associated with the Reformation is far too simple. Though the emphasis on the vernacular in the liturgy is new and overwhelming, the musical cross-currents related to the composition and provenance of those works grouped together as `anthems' are both complex and interrelated. There is a risk of placing too much emphasis on the Reformation itself: many of the stylistic experiments, interchanges and advances in the later sixteenth century English anthem are part of primarily musical and aesthetic changes. They owe their origin to factors that are international and transcend the barriers of sacred and secular: they are as much fruits of the late Renaissance as fruits of the English Reformation. experimental style, and later Latin works (e.g. Tallis's O nata lux 1575) in the same manner. The syllabic style is represented in this anthology by a comparably late example: Farmer's setting of the Lord's Prayer versified by Sternhold and Hopkins from East's volume of metrical psalms (1592). A number of these works were better suited to domestic devotions rather than to the public liturgy. Farmer's Lord's Prayer is one example, and it may be that Sheppard's Our Father, set in motet style at considerable length, was used as an instrumental work on the evidence of some of the sources in which it is found. The macaronic text of Nolo mortem peccatoris suggests a domestic context, possibly related to the tradition of the fifteenth century carol: its ranges and harmonic archaisms have led to speculation that it is an early work, possibly too early to be by Morley (the unique source is Myriell's Tristitiae Remedium 1616). The liturgical placement of the anthem is precisely specified in the Book of Common Prayer: it follows the third collect, and as such is an addition following rather than an entity within the offices of Morning and Evening Prayer. In this it corresponds closely to medieval practice where for at least six hundred years before the Reformation additional antiphons, suffrages, memorials and commemorations had been appended to the principal offices especially in cathedral, collegiate and monastic churches. The best known of these earlier antiphons (or anthems) are those sung in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary at the end of either Vespers or Compline, and in England there was a long tradition of polyphonic performance of such `votive antiphons' which reached a musical peak in the late fifteenth and earlier sixteenth centuries with works whose virtuosity (and insularity) corresponds closely with the spectacular achievements of late perpendicular English architecture. The liturgical precedent for the English anthem in pre-Reformation practice is matched by musical factors. Although Cranmer's remarks related to the setting of the English litany (1545), and isolated injunctions from cathedrals such as Lincoln (1548), imply that the introduction of the vernacular into the liturgy was coupled with a directive for composers to set the texts in an easily intelligible, syllabic style, the musical evidence is more complex. Undoubtedly composers in England (and elsewhere in Europe) turned from devotional texts to setting biblical passages and especially extracts from the book of Psalms. Not only did the same composers set both English and Latin texts (in the case of Byrd, Tallis and others, throughout their lives), but many of the stylistic traits are common to settings in both languages. Though syllabic settings of English anthems are associated with the Edwardian period there are earlier Latin masses by both Tallis and Taverner that employ a similar Secular song influenced the early anthem: Tallis's Purge me, 0 Lord occurs in Mulliner's organ book (mid sixteenth century) with the title Fond youth is a bubble. Both this and Farrant's Hide not thou thy face adopt the formal outline ABB, typical of contemporary English part-songs. Features of musical texture and vocal declamation were taken over into verse anthem from the consort song (normally scored for solo voice and four viols). Byrd's Teach me, o Lord is an early and straightforward example of a festal Psalm (with Gloria) set in this manner: Morley's Out of the deep is a fully fledged verse anthem which demonstrates the assurance of late Elizabethan musical expressiveness in this genre. By far the most important compositional device of the late Renaissance was the development of the technique of polyphonic composition based on successive points of imitation. It allowed composers of vocal music to shape musical points that reflected the accent, outline and affect of each phrase of the text they set, but more importantly it allowed them to generate ongoing abstract musical composition free of scaffolds (e.g. cantus firmus). The roots of this imitative style are found in the Low Countries composers from the time of Josquin and it is especially suited to the motet. Significantly, perhaps, one of the earliest English anthems to attempt this technique is by a Netherlander who worked for many years at the court of King Henry VIII: Philip van Wilder's Blessed art thou is a cautiously imitative setting of a metrical version of Psalm 128. Far more confident and expansive is Tye's I will exalt thee which is set in two separate parts and employs elementary word-painting (`descend into the pit') and a greater variety of vocal texture, especially in the latter part of the anthem. Tye's two-part organisation was a common feature of contemporary Latin motets both in England and abroad, and the motet provided a more direct source for English anthems: a number were adapted to be sung to English words. Two examples of these contrafacta are included: Byrd's O Lord, turn thy wrath with its second part Bow thine ear (which has continued to be a favourite over the centuries) is a direct translation of Ne irascaris / Civitas sancti tui from Cantiones Sacrae (1589), a penitential motet which refers unashamedly to the plight of Roman Catholics in Elizabethan England. In the case of Tallis there is no textual correlation between O sacrum convivium (Cantiones Sacrae 1575) and I call and cry, but there are indications in the musical setting that unusually the English version may have existed first. The stylistic sources and guises of the early English anthem are varied and disparate. By the end of the sixteenth century they had fused to provide the basis of the great blossoming witnessed in the work of Byrd, Gibbons, Tomkins, Weelkes and their contemporaries in the first quarter of the seventeenth century. Nevertheless, the first maturity can be seen not only in a work like Morley's Out of the deep but on a small scale in Tallis's exqisitely shaped O Lord, give thy Holy Spirit or more expansively and extrovertly in Byrd's recently rediscovered Exalt thyself, O God with its confidant imitative motives and bold changes of texture. As this anthology moves on, the emphasis is on anthems intended for use in regular choral services in cathedrals and collegiate foundations, rather than on occasional music. As such, the collection empahises full anthems, and excludes those with accompaniment for ensemble or orchestra. Much of the repertory included here has continued to be performed by choirs since the time it was first written and circulated, in spite of changes in musical style and taste. The high point of Renaissance polyphonic composition was achieved in England in the early years of the seventeenth century, and William Byrd is the father-figure. His setting of Sing joyfully probably dates from the late sixteenth Century, but its clear formal articulation and bold declamation of the text show a modernism that foreshadows the seventeenth Century. A more serious music style is apparent in the setting of O Lord, in Thy wrath by Orlando Gibbons, while O Lord, I lift my heart is a miniature in the partsong tradition. The madrigalian style apparent in some of Byrd's writing is even more striking in the music of Thomas Weelkes. Dramatic power and rhythmic energy exude from Hosanna to the son of David. Of sterner, but no less vibrant stuff, is O Lord arise. Two extremes of Tomkins' style are included here: David's lament for Saul and Jonathan with it's careful declamation and superbly judged climax, and the jubilant O praise the lord, a contrapuntal tour de force for twelve independent voice-parts. The Civil War and the Commonwealth entirely disrupted church music. At the Restoration, the King encouraged new styles from Italy and France, but a synthesis of old and new can be seen in the works of John Blow and his pupil (and colleague) Henry Purcell. The influence of the old imitative tradition is evident in Blow's My God, my God, and in Purcell's Hear my prayer. Purcell's I was glad, and Remember not Lord our offences show two sides of the more modern declamatory style. The imitative and declamatory idioms come together in O God, hast Thou cast us out, an anthem on a larger scale in three distinct sections (the second verse). William Croft's God is gone up is also in three sections (the second verse) and attempts the same synthesis of styles. In Lord, let me know mine end, Maurice Greene may adopt the walking continou bass typical of so many Italian opera arias, but he uses it for the background to highly expressive, contrapuntal choral writing framing a central treble duet. Boyce's O where shall wisdom be found? follows in the tradition of the substantial verse anthems of the seventeenth Century, and pre-figures the large-scale anthems of Samuel Sebastian Wesley. No less striking is the polyphonic setting of O Lord, look down by Jonathan Battishill, with it's growing passion and intensity. Then, a new style. Thomas Attwood studied with Mozart, and a combination of the periodicity of the Classical idiom, and the regular phrasing induced by metrical hymn texts can be heard in his setting of Come, Holy Ghost. Much scorn has been poured on nineteenth century English music, and on English church music above all. Its sentimentality and its spinelessness, its dependence on foreign models and its lack of taste have been ready targets. But it was an important period in its own right. For the Church of England as a whole there were new directions, be they Tractarian or Evangelical. Church buildings were erected and restored at a rate unknown since the fifteenth century. And within the music of the church there were less startling but important changes too. In the first half of the century the English organ which had changed little since the early seventeenth century began to respond to foreign influence. Pedals were added to many existing instruments in cathedrals, and new organs were conceived on a far larger scale and in a more Germanic style. The spread of cheap music printing through the house of Novello brought sheet music to many churches. Choral endeavours flourished in many quarters. Hymns Ancient and Modern, chanted psalms, and plainsong, were explored with zeal in parish churches as well as cathedrals. S S Wesley wrote on a large scale, revealing the influence of foreign composition. Behind his writing there is not only the English oratorio tradition inherited from Handel but the more contemporary impact of Spohr and Mendelssohn. Both anthems included here were composed at Hereford. The Wilderness was written for the opening of the new organ, and the bass aria is a tour de force with its virtuoso pedal part. Around it the anthem assumes the scale of a small cantata. Ouseley's writing looks back to an earlier age. The largely homophonic texture of both anthems heard here is typical of his period, but the use of harmony and especially of suspension is reminiscent of late Renaissance music. Stainer may have lacked the technical compositional control of his near contemporary Stanford (whose music opens Volume Two of this collection), but there is undoubted power in his setting for double choir and organ of I saw the Lord, and evidence of his practical knowledge of choral effect. Whatever the flaws of the repertory of nineteenth century church music, there are striking moments in many of the best works, and overall there is a body of music that displays attention to formal planning, compositional craft and careful declamation of text. This is a repertory that belongs to a Church that is building on solid and optimistic foundations, the product of composers with a strong pedagogic element in their careers. © original notes by Dr John Harper, edited for new collection by James Murray. Professor Harper is currently (2000) Director of the Royal School of Church Music.