Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

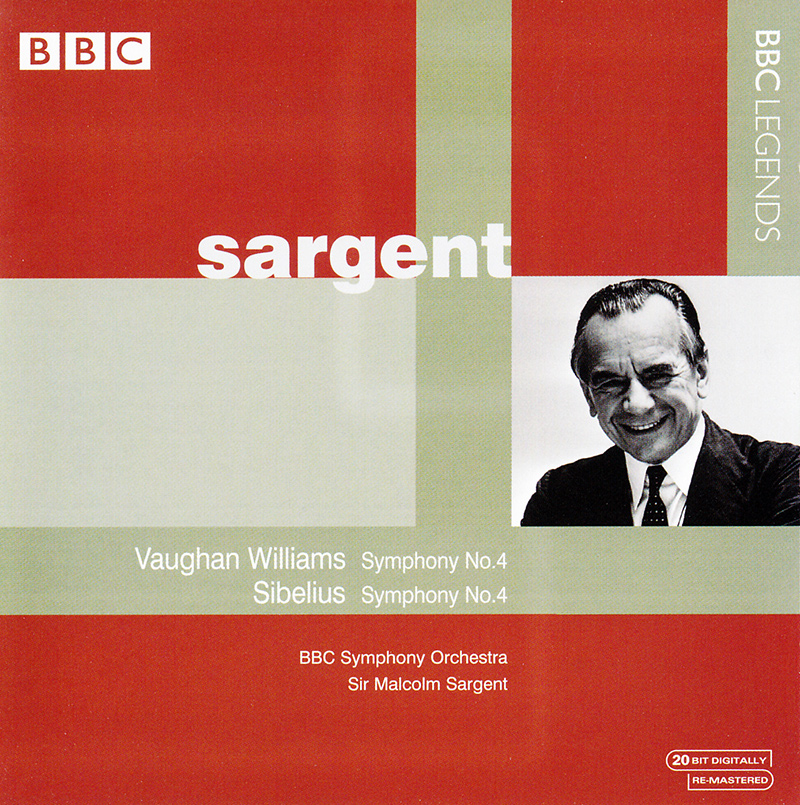

VAUGHAN-WILLIAMS, SIBELIUS, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Sir Malcolm Sargent

Symphony No. 4 in F Minor / Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 63

Two pungent renditions of “difficult” music by Vaughan Williams and Sibelius come to us from Royal Albert Hall, each led by Sir Malcolm Sargent (1895-1967), noted for his sartorial splendor and his elegant handling of large works, especially those involving choral forces. While the recorded music of Sibelius in England tends to “belong” to Sir Thomas Beecham and Sir John Barbirolli, collectors may well recall a vibrant collation of tone poems for EMI that Sargent conducted with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. Unlike Sir Adrian Boult, who inscribed much of Vaughan Williams’ symphonic repertory for commercial distribution, Sargent–who debuted the Ninth Symphony–has only off-the-air broadcasts to testify to his command of this music. The Fourth Symphony performance (16 August 1963) immediately addresses the frenzied convulsions of the score–much of it based on tiny intervals of the second, each vying for expansion–and its uneasy lyricism, as though Vaughan Williams were providing us with visions complementing the angular, tortured visions in Shostakovich. If the BBC does not always render every gesture and note with the pin-point accuracy of the studio-based inscriptions of Boult, they do convey the gloomy and turbulent angst that permeates the score; and here, I think, Sargent accomplishes much of what Mitropoulos brought to this stormy music. The Scherzo, with its tuba-led counterpoint, makes of a bucolic gesture a series of hasty twists and torments. The last movement expounds a kind of post-apocalyptic Epilogue, another dark moment of contrapuntal bleakness, offering few rays of consolation. Visceral, vehement power urges the music forward, a series of metric collisions in which the world ends not with a whimper, but a series of wrenching jolts, awesomely realized. The Sibelius A Minor Symphony reckons itself his “musicians’ symphony,” the most academically compelling of the seven, perhaps more abstractly ambiguous than his more pantheistic excursions in the form. Sargent’s reading (2 September 1965) moves thoughtfully, experimenting with soft hues and degrees of melancholy color in the cellos and violas as the plaintively tense atmosphere evolves. Haunted modal harmonies punctuate the BBC horn section, and the first movement ends with a chorale figure whose colors remind one of the cold pictures of sterile civilization by Giorgio di Chirico. The second movement attempts a playful mood, but the tone still threatens–a la tympanic grumbles and string tremolos–like a concealed weapon in a Hitchcock movie. Suddenly, the Largo appears, its high flute no less haunted by low strings; at times, the ethos of the pained music commends German Expressionism or Sibelius’ admired colleague, Bartok. For the agitated, colorful last movement Allegro, Sargent employs glockenspiel–rather than the colder tubular bells some conductors utilize–to complement the violas and buzzing strings. Flecks and shards of melody canter out of the martial ostinato rhythm, each of the fragments molded with steadfast discipline by Sargent as we move, however circuitously, towards some personal illumination in the midst of cosmic insecurity. A reverent round of applause closes the impressive reading of this singular work. –Gary Lemco