Logowanie

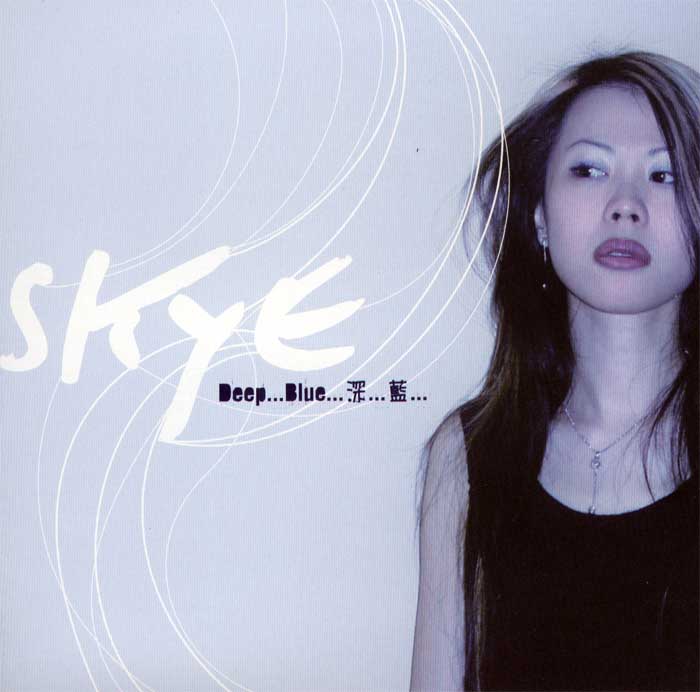

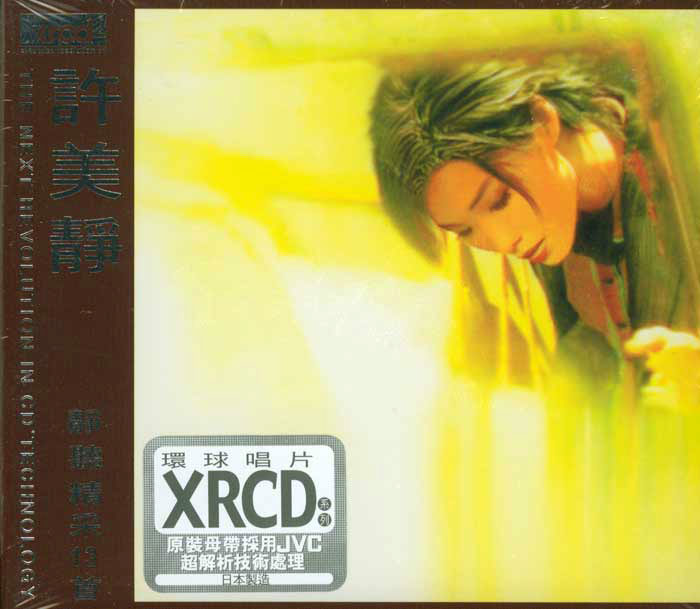

Dlaczego wszystkjie inne nie brzmią tak jak te?

Chai Lang, Fan Tao, Broadcasting Chinese Orchestra

Illusive Butterfly

Butterly - motyl - to sekret i tajemnica muzyki chińskiej.

SpeakersCorner - OSTATNIE!!!!

RAVEL, DEBUSSY, Paul Paray, Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Prelude a l'Apres-midi d'un faune / Petite Suite / Valses nobles et sentimentales / Le Tombeau de Couperin

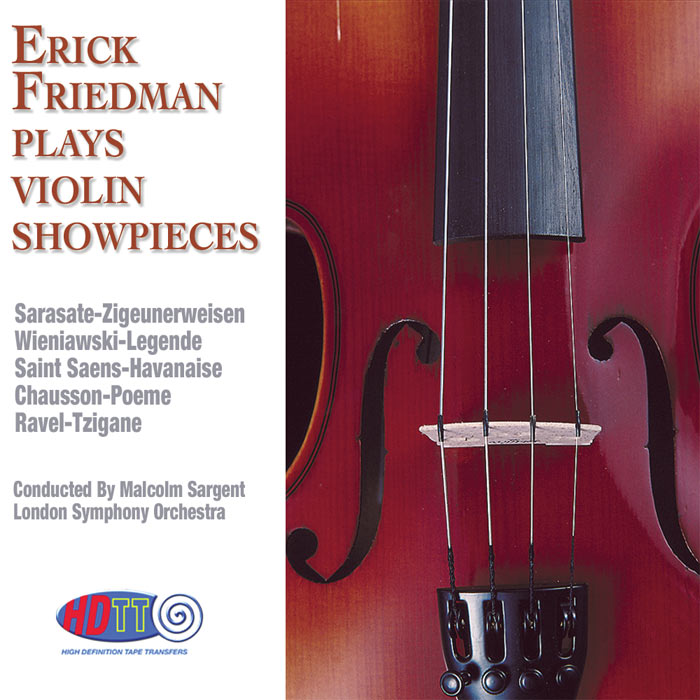

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

PROKOFIEV, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra

Romeo and Juliet

Stanisław Skrowaczewski,

✟ 22-02-2017

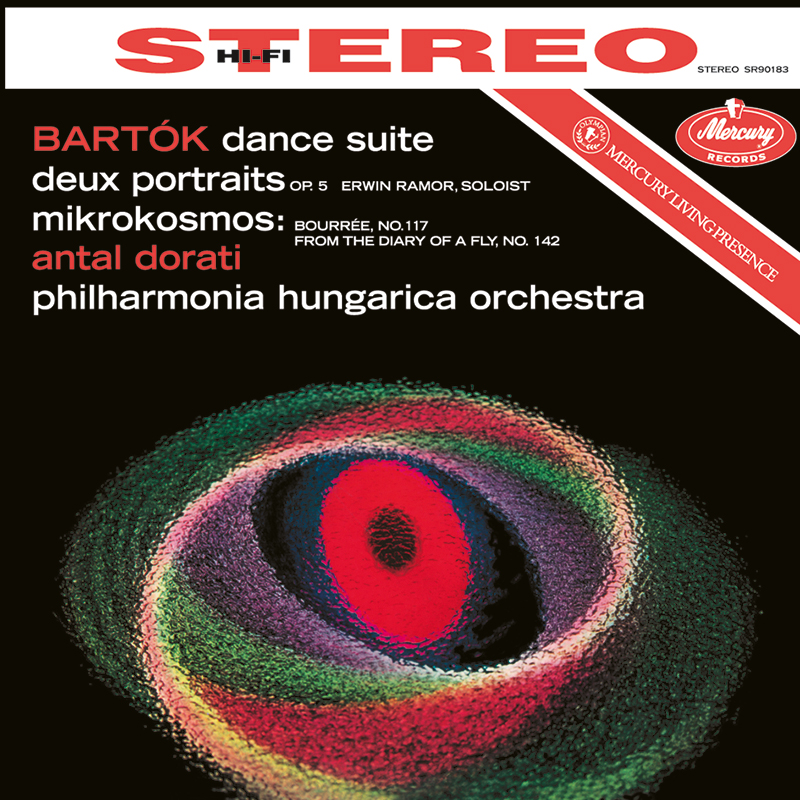

BARTOK, Antal Dorati, Philharmonia Hungarica

Dance Suite / Two Portraits / Two Excerpts From 'Mikrokosmos'

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

ENESCU, LISZT, Antal Dorati, The London Symphony Orchestra

Two Roumanian Rhapsodies / Hungarian Rhapsody Nos. 2 & 3

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

Winylowy niezbędnik

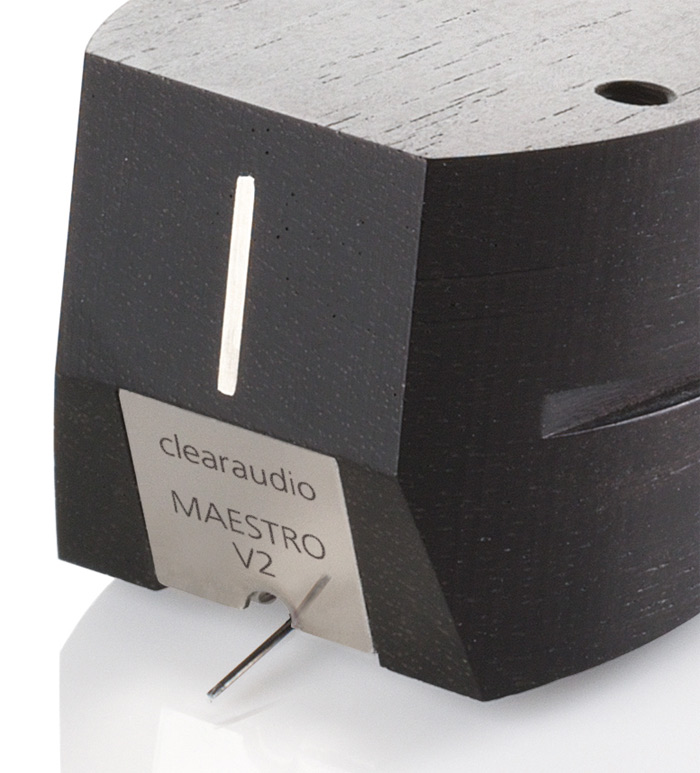

ClearAudio

Cartridge Alignment Gauge - uniwersalny przyrząd do ustawiania geometrii wkładki i ramienia

Jedyny na rynku, tak wszechstronny i właściwy do każdego typu gramofonu!

ClearAudio

Harmo-nicer - nie tylko mata gramofonowa

Najlepsze rozwiązania leżą tuż obok

IDEALNA MATA ANTYPOŚLIZGOWA I ANTYWIBRACYJNA.

Wzorcowe

Carmen Gomes

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 5 - Reference Songs

- CHCECIE TO WIERZCIE, CHCECIE - NIE WIERZCIE, ALE TO NIE JEST ZŁUDZENIE!!!

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Gregor Hamilton

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 2 - Love songs from Gregor Hamilton

...jak opanować serca bicie?...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 1 - Leonardo Amuedo

Największy romans sopranu z głębokim basem... wiosennym

Lils Mackintosh

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 4 - A Tribute to Billie Holiday

Uczennica godna swej Mistrzyni

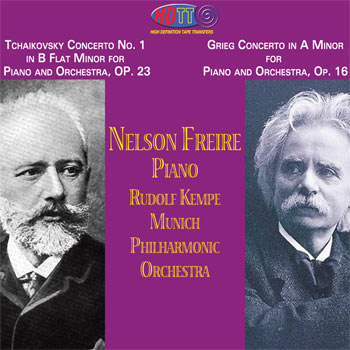

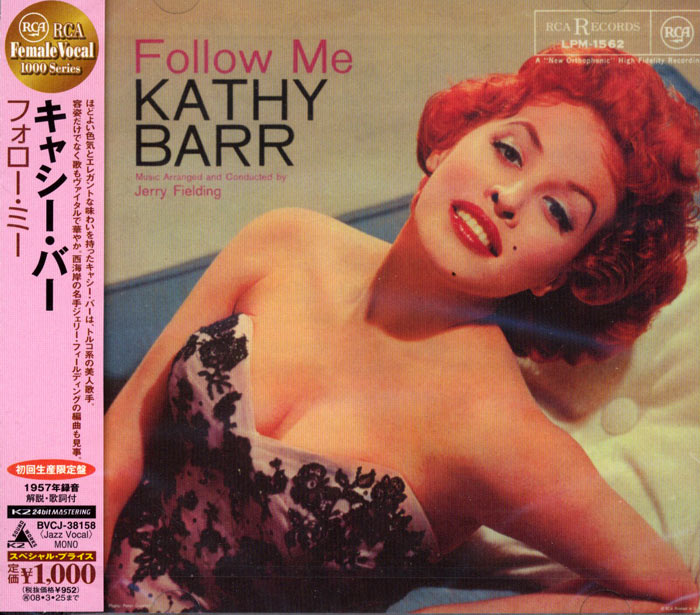

TCHAIKOVSKY, GRIEG, Nelson Freire, Rudolf Kempe

Piano Concerto No. 1 in B Flat Minor, Op. 23 // Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 16

Nagranie dostępne w formatach i na nośnikach:

Płyta CD, bezpośrednia kopia z kompuetra masteringowego, na Gold CD-R

HQCD (High Quality Compact Disc) Płyta do odtworzenia w każdym typie czytników CD i DVD

Studyjny plik FLAC o rozdzielczości 24bit 96khz

Elementy toru masteringowego

• Digital: Digital Audio Denmark AX24 Analog to Digital Converter

• Lynx AES16 used for digital I/O Antelope Audio Isochrone OCX Master Clock

• Weiss Saracon Sample Rate Conversion Software Weiss POW-r Dithering Software

• Analog: Studer 810 Reel to Reel with JRF Magnetics Custom Z Heads & Siltech wiring

• Aria tape head pre-amp by ATR Services

• Manley Tube Tape Pre-amps Modified by Fred Volz of Emotive Audio

• Cables: Purist Audio Design, Pure Note, Siltech

• Power Cords: Purist Audio Design, Essential Sound Products

• Vibration Control: Symposium Acoustics Rollerblocks,Ultra platforms, Svelte shelves

• Sonic Studio CD.1 Professional CD Burner using Mitsui Gold Archival CD's

***********************

Robert Witrak - meloman, audiofil, inżynier jest jednym z nielicznych na świecie kolekcjonerów analogowych taśm z nagraniami wykonanymi w technologii zapisu na dwóch i czterech ścieżkach. Słowem – zbiera taśmy magnetofonowe z profesjonalnie zarejestrowanymi koncertami wielkich orkiestr, słynnych solistów i sławnych dyrygentów. Zbiera materiały źródłowe, najlepsze pod względem jakości i wierności brzmienia, nie przetworzonych, bez ingerencji bezdusznej elektroniki. I, co najważniejsze – utrwalonych w złotych latach współczesnej fonografii. To nagrania o jakości Living Stereo, Mercury Living Presence czy Everest!

Wiele z tych rejestracji uzyskało już status „public domain” – wygasły do nich majątkowe prawa autorskie, nie ma więc ograniczeń formalno-prawnych by pozostawały one w sejfach i magazynach kolekcjonerów. Te cymelia, unikatowe rejestracje, koncerty o wartości historycznej nie mniejszej niż ich walory artystyczne, mogą więc wejść do obiegu kulturowego całego świata. Dzięki firmie HDTT. High Definition Tape Transfers.

Proces reprodukcji tych archiwalnych nagrań zaczyna się od starannego przygotowania taśmy-matki. Musi ona być nie tylko przechowywana w szalenie rygorystycznie warunkach (odpowiednia temperatura, wilgotność, brak obciążeń mechanicznych, nieustanne przekładanie), ale także poddawana specjalistycznej konserwacji. W nieskazitelnym stanie technicznym, zarówno pod względem mechanicznym jak i elektronicznym, musi być utrzymywany cały tor dźwiękowy. Szczególnie ważna jest perfekcyjna praca magnetofonu i stan głowicy. To warunki rzeczywiście wiernego przeniesienia jakości nagrania analogowego na nośnik cyfrowy.

Efekt? Efekt tej benedyktyńskiej pracy, wykonanej z wielkiej miłością do doskonałej jakości muzyki, jest wprost oszałamiający.

NIE ZNAJDĄ PAŃSTWO DZIŚ NA RYNKU NAGRAŃ O JAKOŚCI - W ZAKRESIE DYNAMIKI I PRAWDY BRZMIENIA, A TAKŻE WARTOŚCI ARTYSTYCZNEJ - PORÓWNYWALNEJ ZE STANDARDEM WYZNACZONYM PRZEZ HDTT!

Jakość brzmienia da się porównać tylko do muzyki granej na żywo!

NOŚNIKI.

Aby było możliwe tak wierne odwzorowanie na nośniku cyfrowym jakości analogowego brzmienia, opracowano nowy nośnik i technologię jego przygotowania:

High Quality CD

Jest to nowy standard w dziedzinie zachowania jakości oraz wierności muzyki nagranej w technologii analogowej i przeniesionej na płytę kompaktową, do odtworzenia w każdym typie czytnika na świecie. Autorem tej technologii jest Taiyo Yuden. Wykorzystał on materiały o szczególnej przejrzystości i jednorodności, odpowiednio zabarwione, bezbłędnie wręcz przyjmujące nanoszone na nie informacje. Nagrywanie tych płyt jest procesem długotrwałym, odbywa się w czasie rzeczywistym. Moglibyśmy wręcz użyć określenia – direct-to-disc. Proces nagrywania odbywa się w urządzeniu, które generuje najniższy z notowanych dziś współczynnik błędów (jitter). Innymi słowy – uzyskujemy zapis o najwyższych parametrach. Jako źródło dźwięku wykorzystywany jest studyjny zmodyfikowany magnetofon stacyjny. Dźwięk przetwarzany jest następnie przez renomowane przetworniki Weiss digital A/D. W procesie masteringu używane są audiofilskiej klasy interkonekty oraz komponenty firmy Symposium, tłumiące wibracje i zakłócenia (pinch-rolki, osie, prowadnice).

Technologia HQCD pozwala wytworzyć najlepsze płyty CD na świecie. Dźwięk z nich płynący charakteryzuje się niesłychaną głębią i przejrzystością oraz lepiej rozłożoną sceną muzyczną.

Płyty HQCD nagrane przez HDTT – to zupełnie nowy, nieznany wcześniej wymiar i kosmos dźwięku!

DVD-Audio

Materiały z HDTT dostępne są także w postaci płyt DVD-Audio, do odtworzenia wyłącznie w czytnikach DVD i Blu-ray. Format 24/196 zapewnia nieporównywalną z klasycznymi czytnikami CD jakość odtwarzanej muzyki. Ta kwestia nie podlega żadnej dyskusji.

Pliki FLAC

Jednak najbardziej wyrafinowana postacią materiałów z HDTT są pliki flak o jakości 24bit/96kHz oraz 24bit/192kHz.

FLAC – to format bezstratnej kompresji dźwięku. W przeciwieństwie do innych kodeków dźwięku takich jak Vorbis, MP3 i AAC (każdy z nich powoduje niewielkie ale jednak wyraźnie odczuwane ingerowanie w strukturę danych, powoduje słyszalną kompresję), kodek FLAC nie usuwa żadnych danych ze strumienia audio. Otrzymujemy więc w wyniku dekompresji dźwięk tozsamy z pierwowzorem. Format FLAC jest dziś wykorzystywany przez większość oprogramowania do edycji i odtwarzania dźwięku. Powtórzmy – muzyka z plików FLAC nie ma żadnej konkurencji ze strony innych formatów czy nośników. Jest reprodukowana na wyższym poziomie niż z płyt HQCD.

To byłoby na tyle – chciałoby się przywołać pełne bezpretensjonalności zawołanie poety. Dzięki HDTT, HQCD oraz DVD-Audio a nade wszystko plików FLAC wchodzą Państwa w najbardziej intymny, niczym nie ograniczony związek z Jej Wysokością Muzyką.

Wielu wrażeń!

Nagranie dostępne w formatach i na nośnikach:

Płyta CD, bezpośrednia kopia z kompuetra masteringowego, na Gold CD-R

HQCD (High Quality Compact Disc) Płyta do odtworzenia w każdym typie czytników CD i DVD

Studyjny plik FLAC o rozdzielczości 24bit 96khz

Elementy toru masteringowego

• Digital: Digital Audio Denmark AX24 Analog to Digital Converter

• Lynx AES16 used for digital I/O Antelope Audio Isochrone OCX Master Clock

• Weiss Saracon Sample Rate Conversion Software Weiss POW-r Dithering Software

• Analog: Studer 810 Reel to Reel with JRF Magnetics Custom Z Heads & Siltech wiring

• Aria tape head pre-amp by ATR Services

• Manley Tube Tape Pre-amps Modified by Fred Volz of Emotive Audio

• Cables: Purist Audio Design, Pure Note, Siltech

• Power Cords: Purist Audio Design, Essential Sound Products

• Vibration Control: Symposium Acoustics Rollerblocks,Ultra platforms, Svelte shelves

• Sonic Studio CD.1 Professional CD Burner using Mitsui Gold Archival CD's

***********************

Robert Witrak - meloman, audiofil, inżynier jest jednym z nielicznych na świecie kolekcjonerów analogowych taśm z nagraniami wykonanymi w technologii zapisu na dwóch i czterech ścieżkach. Słowem – zbiera taśmy magnetofonowe z profesjonalnie zarejestrowanymi koncertami wielkich orkiestr, słynnych solistów i sławnych dyrygentów. Zbiera materiały źródłowe, najlepsze pod względem jakości i wierności brzmienia, nie przetworzonych, bez ingerencji bezdusznej elektroniki. I, co najważniejsze – utrwalonych w złotych latach współczesnej fonografii. To nagrania o jakości Living Stereo, Mercury Living Presence czy Everest!

Wiele z tych rejestracji uzyskało już status „public domain” – wygasły do nich majątkowe prawa autorskie, nie ma więc ograniczeń formalno-prawnych by pozostawały one w sejfach i magazynach kolekcjonerów. Te cymelia, unikatowe rejestracje, koncerty o wartości historycznej nie mniejszej niż ich walory artystyczne, mogą więc wejść do obiegu kulturowego całego świata. Dzięki firmie HDTT. High Definition Tape Transfers.

Proces reprodukcji tych archiwalnych nagrań zaczyna się od starannego przygotowania taśmy-matki. Musi ona być nie tylko przechowywana w szalenie rygorystycznie warunkach (odpowiednia temperatura, wilgotność, brak obciążeń mechanicznych, nieustanne przekładanie), ale także poddawana specjalistycznej konserwacji. W nieskazitelnym stanie technicznym, zarówno pod względem mechanicznym jak i elektronicznym, musi być utrzymywany cały tor dźwiękowy. Szczególnie ważna jest perfekcyjna praca magnetofonu i stan głowicy. To warunki rzeczywiście wiernego przeniesienia jakości nagrania analogowego na nośnik cyfrowy.

Efekt? Efekt tej benedyktyńskiej pracy, wykonanej z wielkiej miłością do doskonałej jakości muzyki, jest wprost oszałamiający.

NIE ZNAJDĄ PAŃSTWO DZIŚ NA RYNKU NAGRAŃ O JAKOŚCI - W ZAKRESIE DYNAMIKI I PRAWDY BRZMIENIA, A TAKŻE WARTOŚCI ARTYSTYCZNEJ - PORÓWNYWALNEJ ZE STANDARDEM WYZNACZONYM PRZEZ HDTT!

Jakość brzmienia da się porównać tylko do muzyki granej na żywo!

NOŚNIKI.

Aby było możliwe tak wierne odwzorowanie na nośniku cyfrowym jakości analogowego brzmienia, opracowano nowy nośnik i technologię jego przygotowania:

High Quality CD

Jest to nowy standard w dziedzinie zachowania jakości oraz wierności muzyki nagranej w technologii analogowej i przeniesionej na płytę kompaktową, do odtworzenia w każdym typie czytnika na świecie. Autorem tej technologii jest Taiyo Yuden. Wykorzystał on materiały o szczególnej przejrzystości i jednorodności, odpowiednio zabarwione, bezbłędnie wręcz przyjmujące nanoszone na nie informacje. Nagrywanie tych płyt jest procesem długotrwałym, odbywa się w czasie rzeczywistym. Moglibyśmy wręcz użyć określenia – direct-to-disc. Proces nagrywania odbywa się w urządzeniu, które generuje najniższy z notowanych dziś współczynnik błędów (jitter). Innymi słowy – uzyskujemy zapis o najwyższych parametrach. Jako źródło dźwięku wykorzystywany jest studyjny zmodyfikowany magnetofon stacyjny. Dźwięk przetwarzany jest następnie przez renomowane przetworniki Weiss digital A/D. W procesie masteringu używane są audiofilskiej klasy interkonekty oraz komponenty firmy Symposium, tłumiące wibracje i zakłócenia (pinch-rolki, osie, prowadnice).

Technologia HQCD pozwala wytworzyć najlepsze płyty CD na świecie. Dźwięk z nich płynący charakteryzuje się niesłychaną głębią i przejrzystością oraz lepiej rozłożoną sceną muzyczną.

Płyty HQCD nagrane przez HDTT – to zupełnie nowy, nieznany wcześniej wymiar i kosmos dźwięku!

DVD-Audio

Materiały z HDTT dostępne są także w postaci płyt DVD-Audio, do odtworzenia wyłącznie w czytnikach DVD i Blu-ray. Format 24/196 zapewnia nieporównywalną z klasycznymi czytnikami CD jakość odtwarzanej muzyki. Ta kwestia nie podlega żadnej dyskusji.

Pliki FLAC

Jednak najbardziej wyrafinowana postacią materiałów z HDTT są pliki flak o jakości 24bit/96kHz oraz 24bit/192kHz.

FLAC – to format bezstratnej kompresji dźwięku. W przeciwieństwie do innych kodeków dźwięku takich jak Vorbis, MP3 i AAC (każdy z nich powoduje niewielkie ale jednak wyraźnie odczuwane ingerowanie w strukturę danych, powoduje słyszalną kompresję), kodek FLAC nie usuwa żadnych danych ze strumienia audio. Otrzymujemy więc w wyniku dekompresji dźwięk tozsamy z pierwowzorem. Format FLAC jest dziś wykorzystywany przez większość oprogramowania do edycji i odtwarzania dźwięku. Powtórzmy – muzyka z plików FLAC nie ma żadnej konkurencji ze strony innych formatów czy nośników. Jest reprodukowana na wyższym poziomie niż z płyt HQCD.

To byłoby na tyle – chciałoby się przywołać pełne bezpretensjonalności zawołanie poety. Dzięki HDTT, HQCD oraz DVD-Audio a nade wszystko plików FLAC wchodzą Państwa w najbardziej intymny, niczym nie ograniczony związek z Jej Wysokością Muzyką.

Wielu wrażeń!

- Tchaikovsky

- Concerto No. 1 in B Flat Minor for Piano and Orchestra, OP. 23

- 1) Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso 18:38

- 2) Andantino simplice 7:04

- 3) Allegro con fuoco 6:46

- Grieg

- Concerto in A Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 16

- 4) Allegro molto moderato 12:21

- 5) Adagio 6:19

- 6) Allegro moderato molto e marcato 10:14

- Nelson Freire - piano

- Rudolf Kempe - conductor

- Munich Philharmonic Orchestra - orchestra

- TCHAIKOVSKY

- GRIEG

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky was neither the greatest nor the most innovative musician of his time, yet his contributions to music are still felt today, for it was his gift to write beautiful, evocative melodies that are not easily forgotten. From the love theme of the Romeo and Juliet Overture (1870), to the music of Swan Lake (1877) or his Sixth Symphony (Pathétique, 1893), to the well-known opening of the Piano Concerto No. 1, his music has become almost inescapable, a part of the collective conscious. Yet the oft-told tale of the Piano Concerto's conception reminds us that even Tchaikovsky's melodies could fail to charm. He completed the work in December of 1874, and dedicated it to his teacher and friend, the great Russian pianist Nikolai Rubinstein. Rubinstein's brother Anton had brought Tchaikovsky to Moscow in 1866 as a music theory teacher for the new Moscow Conservatory; Tchaikovsky roomed with Nikolai, and the brothers promoted the young composer's works in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Tchaikovsky was not a pianist and wanted Nikolai's opinion about the suitability of his first piano concerto. So on Christmas Eve, Tchaikovsky played it for his mentor. He described the scene in a letter to a friend: "I played the first movement. Not a word, not a remark. If you only knew how disappointing, how unbearable it is when a man offers his friend a dish of his work, and the other eats and remains silent!" Tchaikovsky played the entire piece and then, he wrote, Rubinstein told him it was "worthless, impossible to play, the themes have been used before ... there are only two or three pages that can be salvaged and the rest must be thrown away!" Rubinstein offered to play the piece if Tchaikovsky rewrote it, but the composer replied, "I won't change a single note," and instead gave it to the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow. Von Bülow did not share Rubinstein's distate, and premiered the work in Boston on October 25, 1875. Though a critic there called it an "extremely dificult, strange, wild, ultra-modern Russian Concerto," the audience was enthusiastic, as was a second audience in New York a week later, demanding an encore of the _nal movement. Rubinstein later recanted and performed the piece as well, while fifteen years later Tchaikovsky made some of the changes Rubinstein had requested. Rubinstein's criticisms still have merit, for the piece is in some places nearly unplayable, while other passages for the soloist are barely audible. And the famous opening theme, for all its grandeur, is just as remarkable in its disappearance -- for after storming in with blaring horns calls, sweeping strings, and maestoso ascending chords from the piano, the theme continues for only 110 measures and simply drops out of the piece, never to be heard again. Yet it is at that point that the first movement, Allegro, may be said to truly begin. Two themes are introduced in double exposition, with the athletic first theme reappearing to interrupt the more restrained second at dramatic moments, and the piano "indulging in cadenza-like flights of startling execution," as the Boston reviewer wrote in 1875. The movement ends in a burst of pyrotechnics from both orchestra and soloist. The gentle Andantino simplice offers a respite from the bold gyrations of its predecessor, with the flute, oboe, and viola taking turns with the solo piano to develop the gentle, lilting _rst theme. The second theme is a rapid scherzo, based on a French song, "Il faut s'amuser, danser et rire" (One must amuse one's self by dancing and laughing), a song favored by the opera singer Désirée Artôt, with whom Tchaikovsky had once been infatuated. The _rst theme for the final Allegro is based on a Ukrainian folk song, "Viydi, viydi Ivanku," (Come, come Ivanku), and it dances up and down in brilliant syncopations. A second, more lyrical theme sweeps in above the virtuosic piano line, and the piano answers in kind. The two themes build to a maestoso tutti followed by bravura fireworks all around. EDVARD GRIEG was born in Bergen, Norway, on June 15, 1843, and died there on September 4, 1907. He began his (only) piano concerto in June 1868, completing the score early in 1869. The first performance took place in Copenhagen on April 3, 1869, with Edmund Newpert as soloist and Holger Simon Paulli conducting the orchestra of the Royal Theater. Grieg made revisions to the concerto in 1872, 1882, 1890, and 1895; he sent the last set of revisions (which included the addition of third and fourth horns) to his publisher on July 21, 1907, six weeks before his death. In addition to the piano soloist, the score of Griegs Piano Concerto calls for an orchestra of two flutes (second doubling piccolo), two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings. Griegs familiar and popular piano concerto was one of the most important steps on his path toward the creation of a national Norwegian music. After completing his course at the Leipzig Conservatory, he returned north and settled in Copenhagen, the only Scandinavian city to have an active musical life. There he met Rikard Nordraak, another Norwegian composer just one year his senior, whose influence on him was to prove decisive, especially after Nordraaks premature death at the age of twenty-four. He spent several years in the musical backwater of Christiana, Denmark, where he was the director of the Philharmonic Society, fighting the good fight for music of real substance on his programs. He was later to look on these years as entirely unproductive, since his time was almost totally taken up with performance rather than composition. Following the birth of a daughter on April 10, 1868, Edvard and Nina Grieg spent a pleasant and productive summer in a cottage at S?ller?c, Denmark, where he experienced a creative outburst that resulted in the Opus 16 concerto. From the very first it has been regarded as Griegs finest large-scale accomplishment (he generally found the small keyboard miniature to be more congenial to his temperament) and as the fullest musical embodiment of Norwegian nationalism in romantic music. The winter following this splendidly fruitful summer was discouraging, as Grieg found himself once again trapped in the indiference and philistinism of Christiana. He had applied for a state traveling grant and had bee rejected; it seemed unlikely that any new application would be favorably received. Then, suddenly, he received a gracious letter from Franz Liszt, apparently unsolicited, in which Liszt expressed the pleasure he had received in perusing Griegs Opus 8 sonata for violin and piano and invited the young composer to visit him in Weimar should the opportunity arise. This letter opened doors that had up to then been firmly shut; not long after, Grieg received his travel grant, which allowed him to take Liszt up on his invitation a year later. In the meantime there was the first performance of the new concerto to be attended to, as well as repeat performances to introduce the work to Denmark and Norway. At about this time, too, he discovered a treasury of Norwegian folk music transcribed into piano score. He delved avidly into the collection and began to realize how a skilled musician could make use of folk elements in his works. From this time Griegs interest in the formal classical genres began to declineof that type, he produced only a string quartet and two sonatas after this date. It took until February 1870 for the Griegs to catch up with Liszt, not in Weimar but in Rome. When they did, though, the result was highly gratifying for the young man. Liszt promptly grabbed Griegs portfolio of compositions, took them to the piano, and sight-read through the G major violin sonata, playing both the violin and piano parts. When Grieg complimented him on his ability to sight-read a manuscript like that, he simply replied modestly, Im an experienced old musician and ought to be able to play at sight. At a later visit, in April, Grieg brought his piano concerto, and this time Liszts sight-reading was even more fabulous: he played at sight from the manuscript score the entire concerto, both orchestral and solo parts, with ever-increasing enthusiasm. Grieg recounted the incident in a letter home: I must not forget one delightful episode. Toward the end of the finale the second theme is, you will remember, repeated with a great fortissimo. In the very last bars, where the first note of the first tripletG-sharpin the orchestral part is changed to G-natural [five bars before the end of the piece], while the piano runs through its entire compass in a powerful scale passage, he suddenly jumped up, stretched himself to his full height, strode with theatrical gait and uplifted arm through the monastery hall, and literally bellowed out the theme. At that particular G-natural he stretched out his arm with an imperious gesture and exclaimed, G, G, not G-sharp! Splendid! Thats the real thing! And then, quite pianissimo and in parentheses: I had something of the kind the other day from Smetana. He went back to the piano and played the whole thing over again. Finally he said in a strange, emotional way: Keep on, I tell you. You have what is needed, and dont let them frighten you. Though the concerto was popular from the start, and was published in full score only three years after its composition, Grieg himself was never entirely satisfied with it, and he continued to touch up details of both the orchestral and solo parts for the rest of his life. A few critics have attacked the worknotably Bernard Shaw (writing as Corno di Bassetto) and Debussyand it has certainly been overplayed and mistreated, especially in a popular operetta, Song of Norway, very loosely based on Griegs life, but it retains its freshness and popularity nonetheless. The basic architecture is inspired by Schumanns essay in the same medium and key, though the piano part is of Lisztian brilliance, blended with Griegs own harmonic originality, which was in turn influenced by his studies of Norwegian folk song. One Norwegian analyst has pointed out that the opening splash of piano, built of a sequence consisting of a descending second followed by a descending third, is a very characteristic Norwegian melodic gesture, and that this opening typifies the pervasiveness of the folk influence. For the rest, the first movement is loaded with attractive themes, some obviously derived from one another, others strongly contrasting, a melodic richness that has played a powerful role in generating the concertos appeal. The animato section of the first movement includes figurations of the type used by folk-fiddlers; the lyric song of the second movement is harmonized in the style of some of Griegs later folksong settings; and the finale consists of dance rhythms reminiscent of the halling and springdans. Edvard Grieg Piano Concerto in A minor, Opus 16