Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

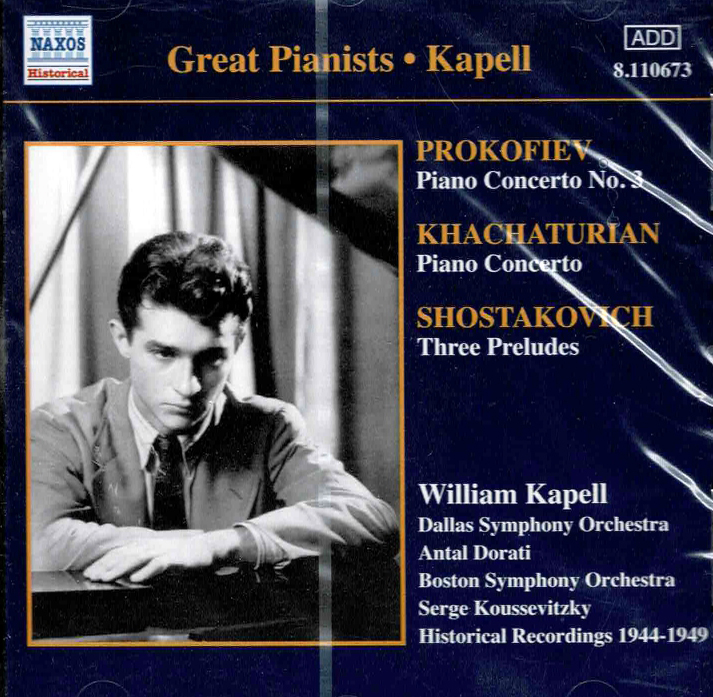

PROKOFIEV, KHACHATURIAN, SHOSTAKOVICH, William Kapell, Antal Dorati, Dallas Symphony Orchestra

Piano Concerto no. 3 in C, op. 26 / Preludes, op. 34: nos. 24, 10, 5 / Piano Concerto in D flat

- William Kapell - piano

- Antal Dorati - conductor

- Dallas Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- PROKOFIEV

- KHACHATURIAN

- SHOSTAKOVICH

William Kapell (1922-1953) was an incredibly gifted young pianist whose life was cut short tragically in a plane crash at the age of 31. But whereas certain artists who left us far too early, Lipatti being the obvious example, and perhaps also Dino Ciani, have become the stuff of legends, the name of Kapell tends to circulate, at least in Europe, among the initiated. The programme of this disc is hardly apt to show how he fared in music that requires more spiritual qualities; but his sizzling fingerwork, his dash, and also his sense of poetry, are revealed to be quite enough to justify a cult following. The Prokofiev, often treated as a lightweight work, a sort of modern Mendelssohn, has its temperament writ large. When it's passionate it is searingly so, when it is brilliant it is dazzlingly so, when it is poetic it is magically so. And the music thrives on such extremes; it is an absolutely riveting performance which, in the last resort, reveals the true stature of the music as few others do. Antal Dorati is such a recent memory that it is strange to think that he was already 43 when he conducted this; he backs Kapell with all the fiery brilliance we know from his famous Mercury recordings of the 50s and 60s. Mark Obert-Thorn has opted, not for the first time, for a sound which brings out as many upper frequencies as the original could reasonably yield, making for a convincing presence of the piano at the expense of some shrillness from the orchestra, particularly the upper strings. It’s not an entirely pleasant sound but for students of great pianism the main thing is that we get a good idea of Kapell himself. The brief Shostakovich Preludes find Kapell penetrating the composer’s sad poetry as well as his irony and his brilliance. The Khachaturian became particularly associated with him, though he later dropped it from his repertoire. I found myself divided between admiration for the fiery virtuosity of the performance and a real difficulty in remaining concentrated on such mind-numbingly stupid music. This piece enjoyed quite a vogue in its day; if a hundred years from now there is the same taste for "interesting revivals" that characterises today’s discographic output, I should hate to think of some well-meaning glutton for punishment dredging this up from deserved oblivion. Except, I suppose, that a recording which shows off pianism like this will ensure the work a degree of immortality. However, I looked out for curiosity a tape of a performance given in Turin in 1963 under the composer’s direction with Sergio Perticaroli as soloist. While Perticaroli had not the devilish fingers of Kapell and the Turin RAI SO was emphatically not the Boston SO, there is an easy, unemphatic musicality about the performance which renders the music considerably more attractive, quite bearable in fact. There is a doggedness about much of the first movement which seems to stem in the first place from Koussevitsky, whereas Khachaturian himself gets the orchestra to play with more swing. Kapell may be very "imaginative" in his almost neurotic underlining of the composer’s counterpoints and counter-melodies in the more lyrical sections, yet Perticaroli’s straightforward concentration on the melodic line leaves a more sympathetic impression. Matters are clinched at the opening of the finale, hard-hitting from Kapell and Koussevitsky, frothy, like a Russian Saint-Saëns, from Perticaroli and Khachaturian. The point seems to be that Kapell’s larger than life approach can be revelatory when the material is strong, as in the Prokofiev, but risks thrashing the daylights out of Khachaturian’s more fragile plant. Still, Kapell was an extraordinarily gifted pianist and if you don’t know his playing you should lose no time in doing so. Indeed, at the Naxos price you might guarantee yourself many fascinating hours by getting both this disc and that of Prokofiev’s own performance of the 3rd concerto. Christopher Howell