Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

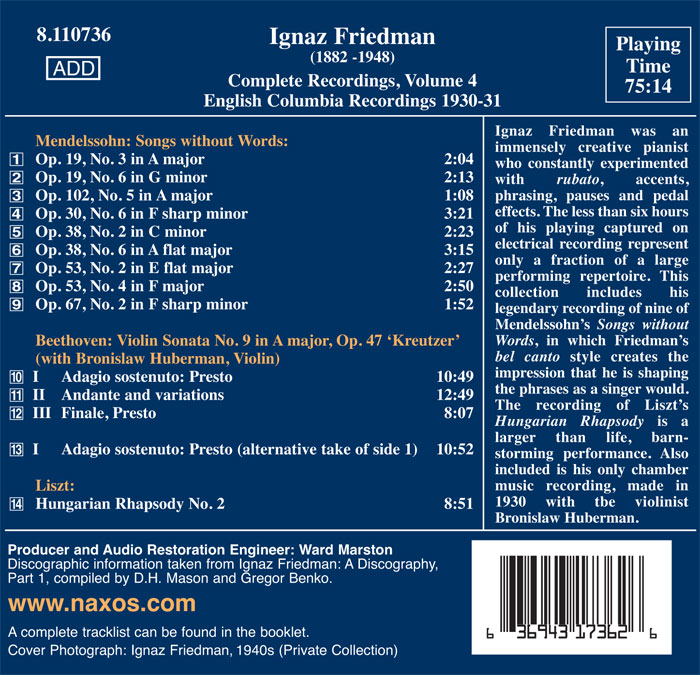

MENDELSSOHN, BEETHOVEN, LISZT, Ignaz Friedman, Bronislaw Huberman

Songs without Words / Violin Soanata 'Kreutzer' / Hungarian Rhapsody 2

- Ignaz Friedman - piano

- Bronislaw Huberman - violin

- MENDELSSOHN

- BEETHOVEN

- LISZT

*** UNIKAT ***

Great Pianists • Ignaz Friedman Complete Recordings Vol. 4 Ignaz Friedman was born, as was Josef Hofmann, in Podgorze, a suburb of the Polish city of Krakow, in 1882. His father was a musician who played in a local theatre orchestra and after piano lessons with a local teacher Flora Grzywinska, Friedman left Krakow in 1900 to study composition at the Leipzig Conservatory with Hugo Riemann. It was not until 1901, when he was already nineteen, that he decided to go to Vienna for lessons with Theodore Leschetizky. As with Moiseiwitsch, Leschetizky was not enthusiastic when the young Friedman presented himself, but after three years of study (also becoming Leschetizky’s teaching assistant), Friedman was ready to make his Vienna début in November 1904 at which he played the D minor Concerto of Brahms, Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto and the E flat Concerto of Liszt. This début launched a touring career that began in 1905, and for the next forty years Friedman seemed to be perpetually on tour; he visited the United States twelve times, South America seven times, and Europe every year, as well as Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, South Africa, Palestine, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. Although he did not often perform chamber music in public he collaborated with the greatest instrumentalists of the day, Casals, Huberman, Feuermann, Morini, Elman, Auer and Ysaÿe, and performed under the batons of Dorati, Gabrilowitsch, Mengelberg and Nikisch. Until 1914 Friedman lived in Berlin but after the First World War he settled in Copenhagen. Friedman’s first visit to America was in 1920 and in April 1923 he made his first records for the American Columbia Company. After extensive and exhaustive touring, the onset of the Second World War meant he had to move again, as Scandinavia was not a safe home for him. The Australian Broadcasting Commission invited him for a tour and during the early 1940s he played and broadcast regularly in Australia and New Zealand. Partial paralysis of his left hand made him retire in 1943 (he was only just over sixty) and he died in Sydney in January 1948. The previous volume in this series of Friedman’s complete recordings contains his famous performances of a selection of Chopin’s Mazurkas (8.110690) mainly recorded in September 1930 for English Columbia. Equally famous is his set of selected Songs without Words by Mendelssohn. Whereas the recording sessions for the Chopin Mazurkas had been plagued with many problems, the nine Songs without Words were recorded on two consecutive days in the middle of September 1930. Friedman does not see these pieces as drawing-room miniatures but paints them on a broad canvas in bold colours. Always to the fore is his glorious tone quality stemming from the bel canto style so much admired in the past by Chopin. In pieces such as the Venetian Gondola Song, Op. 30, No. 6, Friedman creates the impression that he is accompanying a singer, at the same time shaping the melodic phrases as a singer would. The exceptional rich tone quality was a hallmark of the Leschetizky pupils and can be heard often in the playing of Benno Moiseiwitsch, Ignace Paderewski and Mark Hambourg. The famous Duetto in A flat major, Op. 38, No. 6, is one of the best examples of what Friedman could do, perfectly balancing two voices and accompaniment, making the work sound like a song transcription. In a contemporary review published in May 1931, C. Henry Warren wrote, ‘I confess I had for so long taken these Songs without Words for granted that I had almost forgotten how charming some of them were. They were dead bones; but Friedman has blown new life into them for me – as I am sure he will do for many others. He plays them brilliantly; and the whole set is a model of pianoforte recording’. As recently as 1999 the critic Bryce Morrison pertinently wrote, ‘Seemingly as natural as breathing, Friedman’s artistry is quite without (disfiguring) archness, leaving younger pianists to wonder at such insouciance, at such effortless transcending of received wisdom’. The recording of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 is a larger than life, barn-storming performance: the music can take it, and almost needs this type of flamboyant interpretation to make it successful. A contemporary review thought the record would be a milestone in the history of piano recording for the faithfulness of the recorded sound, and of the playing wrote, ‘Throughout, there is a fine gusto in his playing, a sort of vulgarity that attracts at once by reason of its absolute sincerity’. In Friedman’s hands, however, it never completely becomes vulgar; the first section is bold and majestic, at times playful and sentimental. The second part, the friska section, has the excitement of a live performance with Friedman building the tension and holding plenty of sound in reserve for the big key change. At the end he adds a flourish rather than a cadenza. The two sides of the original 78rpm disc were recorded in two sessions on consecutive days in December 1931. At these sessions Friedman attempted further takes of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, Op. 27, No. 2, (some of them being as high as take nine and ten) and recorded three takes of the first side of the Rhapsody. The third take was approved; the previous two, and the nine of the Moonlight Sonata were rejected. What shall remain a great loss were the other titles he recorded during these two days at Abbey Road Studios, for Friedman recorded his own arrangements of Johann Strauss waltzes, O schöner Mai, Wiener Blut, and Künstlerleben, on 16th December and Frauenherz and Rosen aus dem Süden on 17th December. All the sides were rejected, so that from those two days of work at Studio 3 only the Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody was issued. Sadly, none of Friedman’s recordings of his Strauss arrangements were issued, and by now almost certainly would not have survived. Friedman’s only chamber music recording was made at the same time as the Mendelssohn Songs without Words. With the violinist Bronislaw Huberman he recorded Beethoven’s dramatic Kreutzer Sonata, Op. 47. The music suits Friedman well, Beethoven’s drama and impetuosity being perfectly caught by both players. Two takes of side one were issued, one in America and the other in Britain, and both are included for comparison. Friedman played in a trio with Huberman and Pablo Casals, and during his career worked with the world’s greatest violinists including Mischa Elman, Leopold Auer, Carl Flesch and Erica Morini. © Jonathan Summers