Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

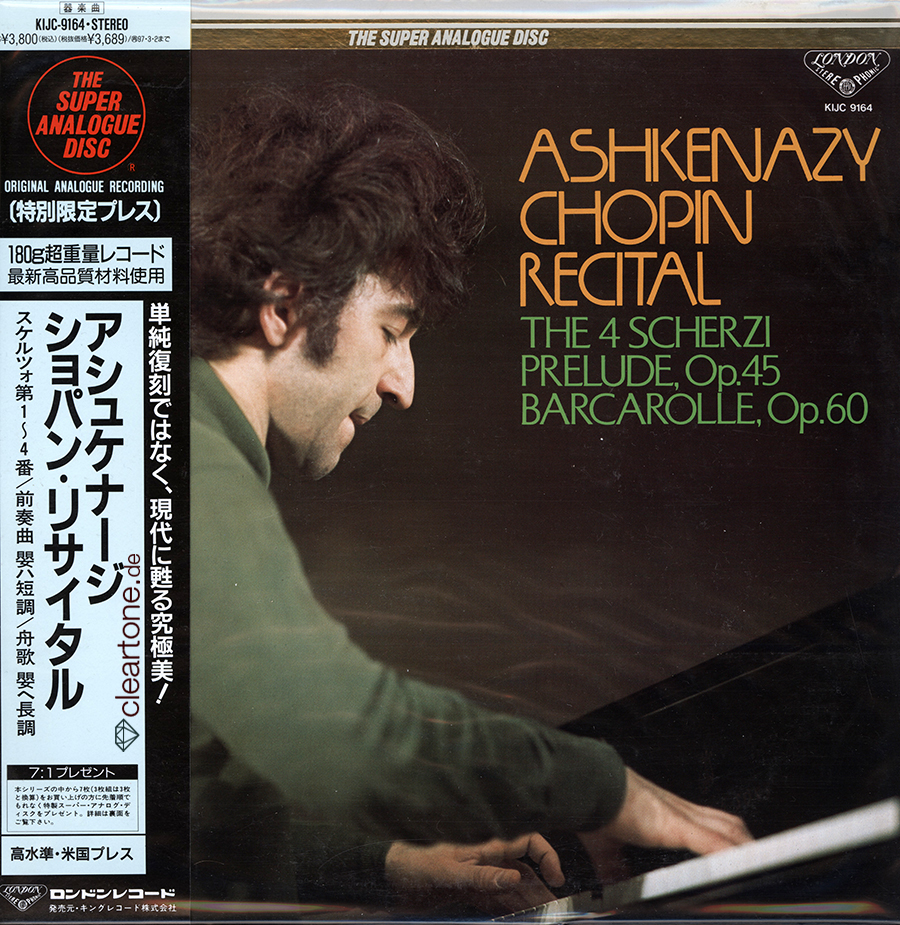

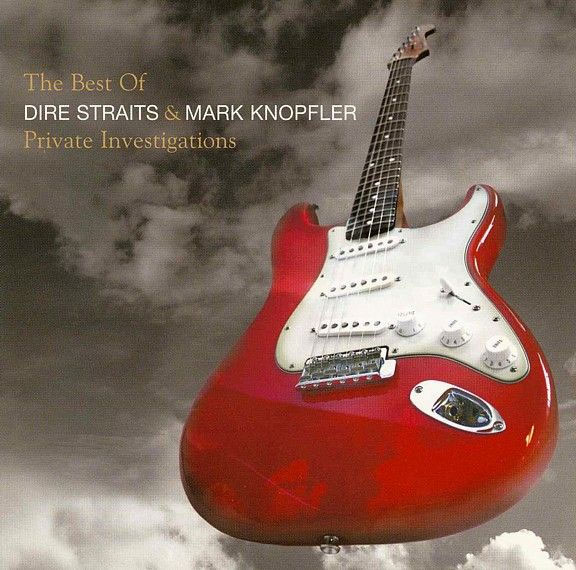

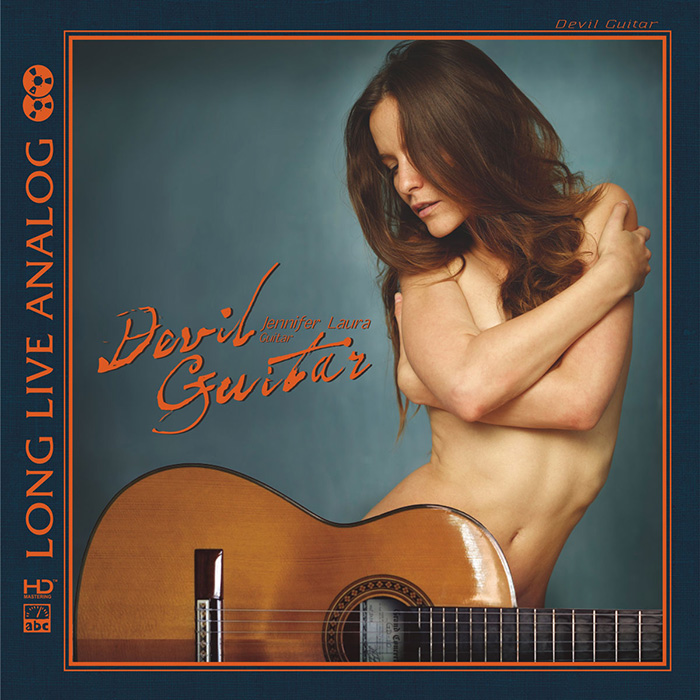

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

MAHLER, GLINKA, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Klaus Tennstedt

Symphony No. 1 in D Major 'Titan' / Ruslan and Ludmilla Overture

Klaus Tennstedt (1926-1998) appeared at Royal Festival Hall, London (28 January 1990) to lead the Mahler First, a performance of alternately transparent and mighty power, gorgeously captured Misha Donat and remastered by Paul Baily. Having already been diagnosed and treated for the throat cancer that would later kill him, Tennstedt admits in his brief interview that a sense of mortality, “of bad things happening,” proves requisite to the translation of Mahler’s corpus of work, since so much of that music is the man himself. Amis points out Tennstedt’s fondness for two Sixths, one by Beethoven, the other by Mahler. The London Philharmonic, moreover, became particularly enamored of and responsive to Tennstedt’s direction, as the inscribed D Major well demonstrates. It seems Tennstedt commands the same respect in Mahler that Jascha Horenstein achieved, a romantic’s vision guided by an acute sensitivity to Mahler’s special nuances. The opening movement, ever lyrically attuned to the song-impulse in Mahler, basks in Mahler’s slowly evolving harmonies, the strings, winds, horns, and harp always forward in our musical consciousness. The pedal points become huge lingering hazes of sound, into which cuckoos and natural vernal sounds pass, impervious to the subjective pain of Mahler’s traveling persona. By the end of the movement, the vivid energies converge and collide in a veritable eddy of transcendental passions. The Scherzo employs any number of thrusting, yodeling motives, mostly based on a song Mahler wrote in 1880, “Hans und Grete.” Tennstedt attacks the rhythms with a passion that finds equal repose in the middle section laendler, which no less carries a cabaret ethos. Old Vienna wafts nigh, as Tennstedt indulges in ornaments and sighs from the Romantic arsenal of interpretation. The last pages explode into Mahlerian fire, the trumpets and basses in dervish throttle. The third movement’s parody funeral procession on “Bruder Martin” plays as though some impish wood demon beckoned us into Pan’s labyrinth. Suddenly, something cheap and tawdry from the streets in drum and cymbal emerges, a clear whisper to the young Kurt Weill. Even so, Tennstedt invests this reminder of man’s “love of the mud” with a plaintive hue of longing humanity. The quotations from The Songs of a Wayfarer, especially the seeking of solace from a relentless, loveless world, become haunted by rue and nostalgia. When the grim variant from Frere Jacques returns, it has all of the irony of the last scene of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The entire last movement becomes both Mahler’s and Tennstedt’s fervent search for spiritual victory in the midst of moral crisis. Somewhat like Don Quixote, Mahler will be daunted by moments of dark despair before seven horns announce fate’s capitulation at the finale. The lyrically bucolic sections often quote from Mahler’s discarded “Blaumine” (flowers) movement. We now hear these restful points of quietude as hymns for our departed conductor. Tennstedt wants his brass to convey the shredding power of fate as well as the descending four-note “fate” motif clearly nodding to Herr Beethoven. The struggles subside, only to rise, De Profundis, with renewed frenzy, a “darkling plain” where contrapuntal convulsions of the spirit fight it out in Tennstedt‘s superheated vision. At the last upheaval, Mahler’s synthesis of Heaven and Hell, the audience at Royal Festival Hall erupt in wild appreciation. Glinka’s spirited Ruslan and Lyudmila (28 August 1981) has Tennstedt’s competing with Mravinsky to see who can render the furious tide of notes and kettledrum throttles faster. Mravinsky wins, but not for lack of desire from the LPO under Tennstedt. The secondary theme, all Russian soul by way of Italian opera, sings out grandly. Affection and impetuosity converge in happy harmony for the thrilling last pages, the LO in full bravura form. They did love their Klaus. –Gary Lemco