Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

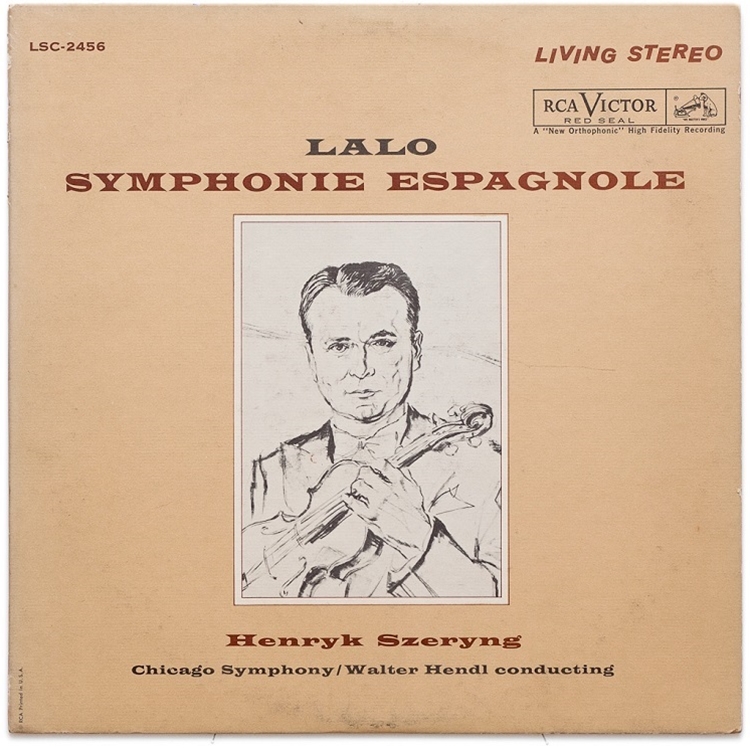

LALO, Henryk Szeryng, Walter Hendl, Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Symphonie Espagnole / Capriccio Espagnol

- SYMPHONIE ESPAGNOLE

- 1. Allegro non troppoe

- 2. Allegro molto

- 3. Allegretto non troppo

- 4. Andante

- 5. Rondo - Allegro

- CAPRICCIO ESPAGNOL

- 6. Alborada;

- Variations;

- Alborada;

- Scene and Gypsy Song;

- Henryk Szeryng - violin

- Walter Hendl - conductor

- Chicago Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- LALO

"These are the best vinyl releases of RCA LPs I've yet heard." — Jonathan Valin, executive editor, The Absolute Sound

Edouard Lalo (b Lille, 27 Jan 1823; d Paris, 22 April 1892). French composer. His father had fought for Napoleon and although the name was originally Spanish, the family had been settled in Flanders and northern France since the 16th century. Lalos parents at _rst encouraged musical studies and he learnt both the violin and the cello at the Lille Conservatoire, but his more serious inclinations towards music met with stern military opposition from his father, compelling him to leave home at the age of 16 to pursue his talent in Paris. He attended Habenecks violin class at the Paris Conservatoire for a brief period and studied composition privately with the pianist Julius Schulhoff and the composer J.-E. Cr?vecoeur. For a long while he worked in obscurity, making his living as a violinist and teacher. He became friendly with Delacroix and played in some of Berliozs concerts. He was also composing and two early symphonies were apparently destroyed. In the late 1840s he published some romances in the manner of the day and some violin pieces; his inclination was, unfashionably, towards chamber music. By 1853 he had composed two piano trios, a medium almost entirely neglected in France at the time.

The revival of interest in chamber music in France in the 1850s owed much to Lalo, for he was a founder-member of the Armingaud Quartet, formed in 1855 with the aim of making better known the quartets of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and also of Mendelssohn and Schumann; Lalo played the viola and later second violin. His own string quartet dates from 1859. A period of discouragement then ensued and Lalo wrote little until 1866 when, at the age of 43, he embarked on an opera in response to a competition set up by the Théâtre-Lyrique. His Fiesque, a grand opera in three acts to a libretto by Charles Beauquier after Schillers play Fiesco, was not awarded the prize and, despite interest shown by both the Paris Opéra and the Théâtre de la Monnaie, Brussels, it was never performed.

Lalo was embittered by these refusals and had the vocal score published at his own expense. He valued the work highly and drew on it for numerous later compositions, including the scherzo of the Symphony in G minor, the two Aubades for small orchestra, the Divertissement, Néron and other works. Lalos fame as a composer was greatly widened in the 1870s by the performance of a series of important instrumental works.

The formation of the Société Nationale and the support of Pasdeloup, Lamoureux, Colonne, Sarasate and others gave Lalo an opportunity to pursue his ambitions as a composer of orchestral music in an essentially German tradition. The F major violin concerto was played by Sarasate in 1874 and the Symphonie espagnole, also by Sarasate, the following year. His cello concerto was played by Fischer in 1877 and the Fantaisie norvégienne in 1878. The Concerto russe for violin was _rst played by Marsick in 1879. Despite this highly productive period devoted to orchestral music, the composition of Fiesque had satis_ed Lalo that he should continue to seek success in the theatre and in 1875 he began work on a libretto by Edouard Blau based on a Breton legend, Le roi dYs. By 1881 it was substantially completed and extracts had been heard in concerts. But no theatre accepted it, and the Opéra, perhaps as consolation for turning it down, asked Lalo instead for a ballet (a genre that I know nothing about, he admitted) to be completed in four months.

Namouna was composed in 18812 (when Lalo su_ered an attack of hemiplegia Gounod helped with the orchestration) and played at the Opéra the following year. The production was beset with intrigue and survived only a few performances. Lalos music was variously criticized as that of a symphonist or a Wagnerian or both, but the more discerning critics appreciated its freshness and originality. Debussy, then a student at the Conservatoire, remained an enthusiastic admirer of the score and it became popular in the form of a series of orchestral suites. More orchestral works followed, notably the symphony and the piano concerto, but Lalos main attention was given to the production of his masterpiece Le roi dYs, finally mounted at the Opéra-Comique on 7 May 1888. It was an overwhelming success and for the remaining four years of his life Lalo _nally enjoyed the general acclaim he had sought for so long. Although he worked on two more stage works, the pantomime Néron staged at the Hippodrome in 1891 and La jacquerie, an opera of which he completed only one act, both drew almost entirely on earlier compositions; his productive life was essentially over.

In 1865 Lalo had married one of his pupils, Julie de Maligny a singer of Breton origin; their son was Pierre Lalo. Although Lalos fame has rested, in France at least, on Le roi dYs, his instrumental music must be accorded a more prominent historical importance, for it represents a decisively new direction in French music at that period, taken more or less simultaneously by César Franck and Saint-Saëns. Outside France the Symphonie espagnole, a violin concerto in _ve movements using Spanish idioms and whimsically entitled symphony, has remained his most popular work; the freshness of its melodic and orchestral language is imperishable. The cello concerto is on the whole a stronger and more searching work, with a central movement that combines slow movement and scherzo as Brahms was wont to do, and a forward momentum, especially in the first movement, of exceptional power. In his Symphony it is the two central movements, a scherzo and an adagio (both drawn from earlier music) which carry the weight of the argument. The piano concerto is disappointing, but the string quartet, composed in 1859 and revised in 1880, and the second piano trio are both works that deserve to be heard more frequently.

The opera Fiesque is encumbered with a libretto laden with absurdities and awkward stage manoeuvres, belonging in spirit to the age of Scribe. Yet for a _rst opera the music is extraordinarily deft and varied, occasionally pompous but never dull, and full of brilliantly successful numbers. The Divertissement, drawn from the opera, is one of Lalos most effective orchestral pieces. Le roi dYs is a fine opera too, with some borrowing of the conventional scenes of grand opera, such as the offstage organ with ethereal voices. Margared is well characterized, especially in her expressions of anxiety or horror, and Rozenn has music of winning tenderness. The choral music is less convincing, for Lalo seems inadequate to the task of collective characterization except when the chorus are being conventionally decorative, as for example in the exquisite wedding scene. The opera has considerable dramatic force and a genuine individuality of style. Many of Lalos songs were written for his wifes contralto voice. They form a more sentimental, lyrical part of his output in notable contrast to the instrumental music. His gift in this area was already evident in the Six romances populaires of 1849 and the Hugo settings of 1856. Lalos style is robust and forceful with fresh rhythmic and harmonic invention. He was accused, like all progressive composers of his time, of imitating Wagner but although he admired Wagner, their styles have little in common. As Lalo himself said: Its hard enough doing my own kind of music and making sure that its good enough. If I started to do someone elses Im sure it would be appalling.

His favourite harmonic colour is the soffcalled French 6th, which is almost overused, but he did turn harmonic progression to _ne e_ect as a source of forward momentum. His orchestration is noisy but ingenious; Namouna is a particularly skilful score. He had an evident fondness for scherzo movements in 6/8, 3/8 and even 3/16. Another hallmark is a recurring emphatic chord (often an octave), fortissimo, commonly on an unexpected beat of the bar; in his orchestral music this mannerism can be brusque or crude in effect. His temperament was naturally tuned to the styles of Mendelssohn and Schumann on which he superimposed a variety of colours, sometimes drawn from folk idioms of Scandinavia, Russia, Brittany or Spain. All his music has a vigour and energy that place it in striking contrast to the music of Francks pupils on the one hand and the impressionists on the other. His kinship is more with the Russians, especially Borodin, and with Smetana, than with composers of his own country, although it is not dificult to _nd traces of his in_uence in Dukas and Debussy and perhaps more distinctly in Roussel. Szeryng, Henryk, celebrated Polish-born Mexican violinist and pedagogue; b. Zelazowa Wola, Sept. 22, 1918; d. Kassel, March 3, 1988. He commenced piano and harmony training with his mother when he was 5, and at age 7 turned to the violin, receiving instruction from Maurice Frenkel; after further studies with Flesch in Berlin (1929-32), he went to Paris to continue his training with Thibaud at the Conservatory, graduating with a premier prix in 1937. On Jan. 6, 1933, he made his formal debut as soloist in the Brahms Concerto with the Warsaw Philharmonic With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, he became o_cial translator of the Polish prime minister Wladyslaw Sikorski's government-in-exile in London; later was made personal government liaison oficer.

In 1941 he accompanied the prime minister to Latin America to _nd a home for some 4,000 Polish refugees; the refugees were taken in by Mexico, and Szeryng, in gratitude, settled there himself, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1946. Throughout World War II, he appeared in some 300 concerts for the Allies. After the war, he pursued a brilliant international career; was also active as a teacher. In 1970 he was made Mexico's special adviser to UNESCO in Paris. He celebrated the 50th anniversary of his debut with a grand tour of Europe and the U.S. in 1983. A cosmopolitan fuent in 7 languages, a humanitarian, and a violinist of extraordinary gifts, Szeryng became renowned as a musician's musician by combining a virtuoso technique with a probing discernment of the highest order.