Logowanie

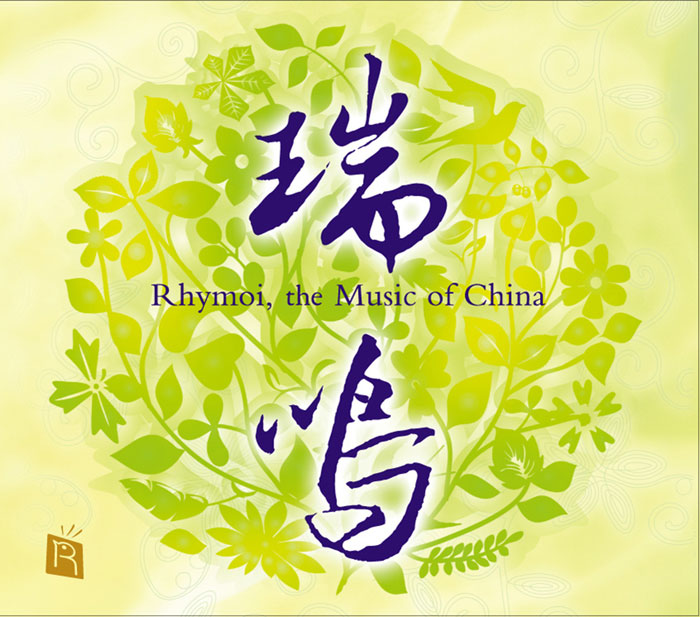

Dlaczego wszystkjie inne nie brzmią tak jak te?

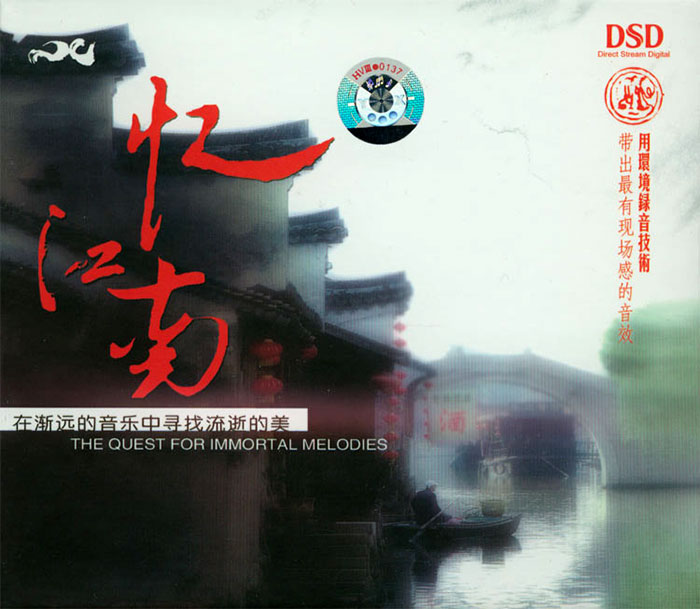

Chai Lang, Fan Tao, Broadcasting Chinese Orchestra

Illusive Butterfly

Butterly - motyl - to sekret i tajemnica muzyki chińskiej.

SpeakersCorner - OSTATNIE!!!!

RAVEL, DEBUSSY, Paul Paray, Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Prelude a l'Apres-midi d'un faune / Petite Suite / Valses nobles et sentimentales / Le Tombeau de Couperin

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

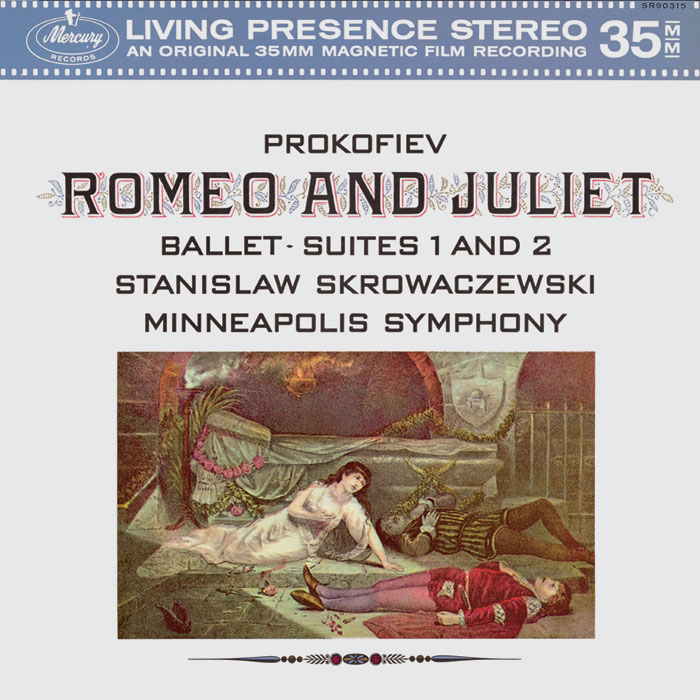

PROKOFIEV, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra

Romeo and Juliet

Stanisław Skrowaczewski,

✟ 22-02-2017

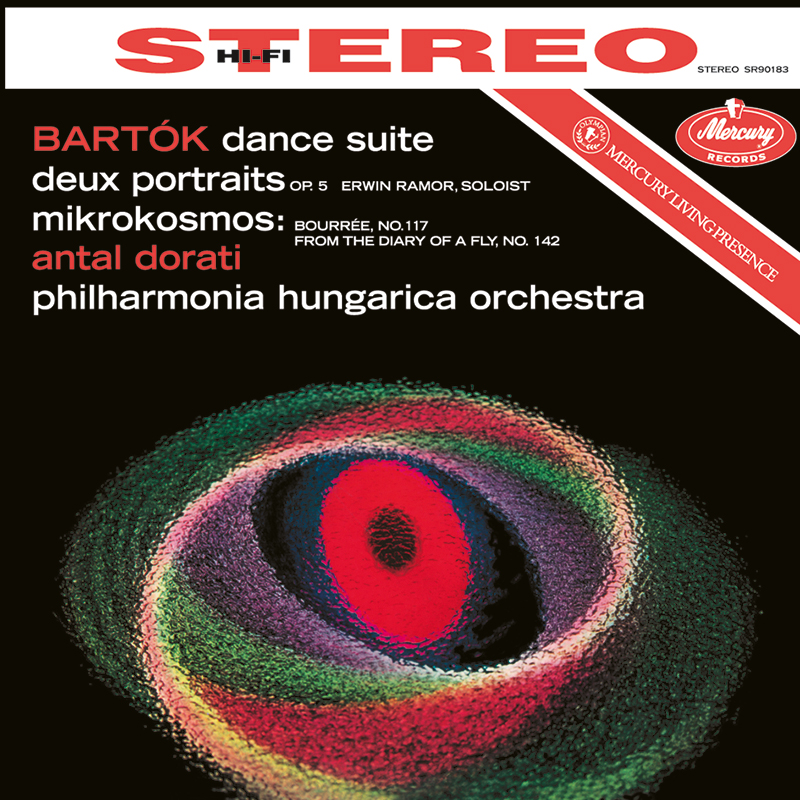

BARTOK, Antal Dorati, Philharmonia Hungarica

Dance Suite / Two Portraits / Two Excerpts From 'Mikrokosmos'

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

ENESCU, LISZT, Antal Dorati, The London Symphony Orchestra

Two Roumanian Rhapsodies / Hungarian Rhapsody Nos. 2 & 3

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

Winylowy niezbędnik

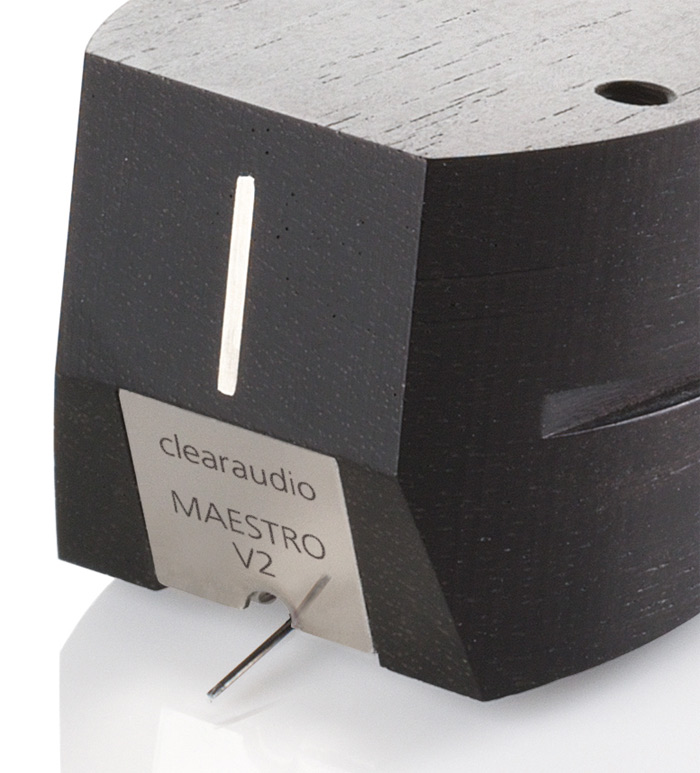

ClearAudio

Cartridge Alignment Gauge - uniwersalny przyrząd do ustawiania geometrii wkładki i ramienia

Jedyny na rynku, tak wszechstronny i właściwy do każdego typu gramofonu!

ClearAudio

Harmo-nicer - nie tylko mata gramofonowa

Najlepsze rozwiązania leżą tuż obok

IDEALNA MATA ANTYPOŚLIZGOWA I ANTYWIBRACYJNA.

Wzorcowe

Carmen Gomes

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 5 - Reference Songs

- CHCECIE TO WIERZCIE, CHCECIE - NIE WIERZCIE, ALE TO NIE JEST ZŁUDZENIE!!!

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Gregor Hamilton

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 2 - Love songs from Gregor Hamilton

...jak opanować serca bicie?...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 1 - Leonardo Amuedo

Największy romans sopranu z głębokim basem... wiosennym

Lils Mackintosh

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 4 - A Tribute to Billie Holiday

Uczennica godna swej Mistrzyni

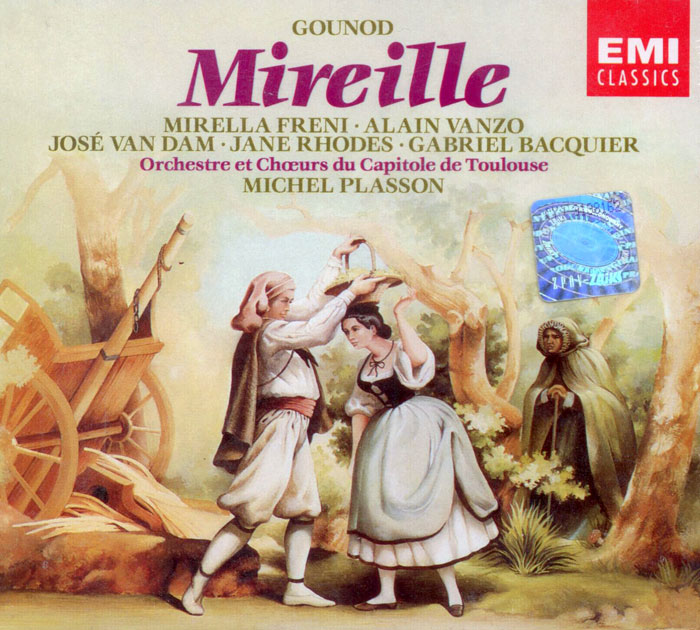

GOUNOD, Mirella Freni, Alain Vanzo, Jose van Damm, Jean-Jacques Cubaynes, Michel Plasson

Mireille

- Mirella Freni - soprano

- Alain Vanzo - tenor

- Jose van Damm - bass

- Jean-Jacques Cubaynes - bass

- Michel Plasson - conductor

- Toulouse Capitole Orchestra - orchestra

- GOUNOD

Four years after Faust had appeared, Gounod read a poem on epic scale originally written in Provençal, Mireio by Frédéric Mistral. It fired him with the idea of using the subject for an opera. He had a libretto written by Michel Carré in collaboration with Mistral himself, and to find inspiration he took up residence in Provence at Saint-Rémy where Mistral lived. In idyllic surroundings he set to work on the score, and significantly the first passages written were the happy inspirations, reflecting the pastoral side of the story rather than the bitterness which develops and the ultimate tragedy. The work actually starts with a chord of Beethovenian solemnity (later used to introduce the scene in Act 4 when the heroine is improbably dying in a desert—significant model for Puccini in Manon Lescaut) but quickly the happy side of Gounod's imagination takes over, and long before the end of the prelude one is thinking of Sullivan, above all in a melody associated with the hero, Vincent (A poor basket-weaver's son understandably rejected by the heroine's rich father) which skips along exhilaratingly in compound time over pizzicato bass. The curtain rises on a chorus of mulberry-pickers, suggesting that Tchaikovsky (for Eugene Onegin) as well as Puccini picked up a few ideas from this opera. In the first scene of Act 4 there is even a shepherd piping off-stage at dawn as the heroine sings a plaintive aria, a direct model for the scene following Tatiana's letter-song. The first act is a delight, and at this remove it seems a pity that Gounod's subject was such a poem, when in its easy, sparkling lyricism set against young love freshly and totally found, that start could have led to an opera as innocent and happy as L'elisir d'amore or L'amico Fritz. As it is, it is striking that Gounod in dark mood and minor key is notably less inspired—and certainly less memorable—than when he is pouring forth his most characteristic melodies usually in triple or compound time with here an admixture of local colour. Act 2 opens with a Farandole for the chorus before the St John's Feast horse-race in the amphitheatre at Aries, and the race itself is signalled with a fanfare. The song of Magali, which forms the basis of the duet for hero and heroine which follows, was recomposed from a folk-source with Gounod keeping a rustic flavour not just in the simple melody but in the alternation of bar-lengths, 9/8 and 6/8. Fairly enough Gerard Condé in his notes for this set suggests that Bizet was directly influenced by Mireille when it came to writing his Arlésienne music (not to mention Carmen); but any mention of Carmen brings it home very strongly how weak by comparison the story-line of Mireille is, not so much a plot as a sequence of excuses for arias and scenas. Gounod made the mistake—readily understandable in the heyday of Der Freischfltz but before Carmen—of introducing scenes of the supernatural at the Val d'enfer and Rhone. There are lightweight echoes of Weber's Wolf's Glen leading to the drowning of Ourrias, a boastful and unappealing suitor of Mireille, at the hands of a phantom boatman. Textually Mireille has had a difficult time over the years, and Gerard Condé outlines the various revisions and developments, some sanctioned by Gounod, some forced upon him, and some devised long after his death. At some stages there was even a happy ending in place of the heroine's death. One trouble was that he originally made demands on the soprano who takes the role of Mireille which were too great for a coloratura as light as Mme Carvalho, wife of the head of the Opéra-Comique. She had asked for "something dazzling", only to find dramatic demands made in the scene "in the desert". Saint-Saëns in his memoirs reported a visit to Gounod. "'Madame Carvalho,' said I, 'will never sing that!"—"'She will just have to sing it,' he replied, opening wide murderous eyes." Later when the two heavier scenes were omitted (Act 3) Gounod was persuaded to write an "acrobatic waltz" for Mme Carvalho, but at one point he actually sent a bailiff to the theatre to demand its suppression. The present recording uses the text which Henri Busser published in 1939, aiming so far as possible at restoring the original text of 1869. Those who know "Légére hirondelle" from separate recordings (Joan Sutherland's version is one of two arias which represent this opera in the current catalogue) may be disappointed that there is no sign of it here: with a singer as versatile as Freni it would have made a good supplement. On record Mireille was treated to a sudden burst of attention in the mid-fifties. Simultaneously in the summer of 1954 Decca issued two separate collections of five numbers each, and the following year a complete version appeared conducted by André Cluytens with the young Nicolai Gedda as the hero, Vincent, as well as Janette Vivalda as Mireille. That was in mono and disappeared within a few years, which makes this present version very welcome with Michel Plasson conducting a generally colourful and committed performance in which rhythms are well sprung. When for moments of uplift Gounod turns to the more sugary style with which rather unfairly he came so much to be associated (the introduction of the organ into the orchestral texture a danger sign) Plasson's directness avoids sentimentality without underplaying what Gounod intended. No doubt with her own Christian name echoing that of the heroine Mirella Freni was a self-evident choice for the recording. Nowadays there is a hint of unevenness in the production, the legato phrasing is less sweet and pure than it would have been a few years ago—as in the Act 2 aria "Mon coeur ne peut pas changer"—but then that relatively simple cantilena bursts into a cabaletta with coloratura like a square-rhythmed version of the Jewel Song and Freni accomplishes it beautifully. She does not sound sad at all in her Act 4 reprise of the Magali Song, but then the music itself is partly to blame. She is at her radiant best in the duets opposite Alain Vanzo, now with less bloom on the voice but still most stylish in his singing, a tenor I have long felt has been wrongly neglected by the record companies. José van Dam in the unappealing role of the suitor, Ourrias, yet makes the most both of his boastful first aria (L'elisir d'amore again recalled) and of the improbable drowning scene. Gabriel Bacquier is splendid as the heavy father of the heroine, Ramon, and though Jane Rhodes as the sorceress, Taven, produces rich, resonant tone, she sits under the note too regularly for complete comfort. Other smaller roles are generally well taken, but the chorus is in some ways the protagonist, actually starting four of the five acts and in the remaining one (Act 3) appearing at the start in communal conversation with Ourrias. It is a mark of the quality of the Toulouse Choir's singing that even without help from the libretto one can hear most of the words. The recording like most of those that Pathé Marconi has made with Plasson in Toulouse is warmly atmospherc, undistractingly so. Though the flaws of the piece are very evident, it has so much of charm in it, that a recording such as this is most persuasive. Who knows, it may have to last us another 25 years until the next recording. -- E.G., Gramophone [12/1980] Reviewing original release Uczestnicy nagrania: Mirella Freni (Soprano), Jean-Jacques Cubaynes (Bass), José Van Dam (Bass Baritone), Alain Vanzo (Tenor), Jane Rhodes (Mezzo Soprano), Christine Barbaux (Soprano), Gabriel Bacquier (Bass), Michèle Command (Soprano), Marc Vento (Bass Baritone) Conductor: Michel Plasson Toulouse Capitole Orchestra, Toulouse Capitole Chorus