Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

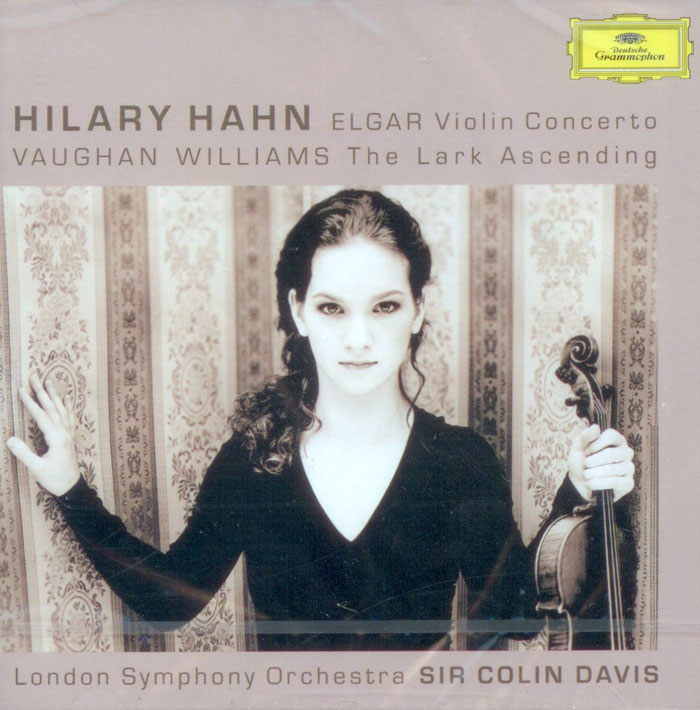

ELGAR, VAUGHAN-WILLIAMS, Hilary Hahn, Sir Colin Davis, The London Symphony Orchestra

Violin Concerto / The Lark Ascending

This disc asks more questions than it answers. Why did Hilary Hahn record the Elgar concerto at this stage of her career? Why did Deutsche Grammophon release this disc? What did Sir Colin Davis, a notable, though not great, Elgarian make of his young soloist? Whatever happened to Hilary Hahn’s famed interest in the techniques of the past masters of her chosen instrument? In short, this is a deplorable disc that, even after two intensive hearings, this reviewer has found a quite fruitless musical experience. Not writing about it may have been a kinder gesture but some kind of review is necessary, if only to steer buyers away from a disastrous purchase. What does most injury to this performance is the sheer lack of empathy the soloist has with Elgar’s idiom, and that is death in any performance. After the LSO’s portentous opening to the work Hahn enters with limply defined tone and half-hearted expression. What should be a moment of magical wonder (identical almost to the soloists first entry in Beethoven’s concerto) passes as nondescript ambivalence. Wiry tone defaces her performance here and throughout the work; she literally scratches at the surface of this works treasures. One was tempted at first to blame the recording – quite the opposite of Perlman, who is often too close to the microphone, Hahn seems to be a transatlantic liner away from one – but in fact it is clear and spacious with a decent enough acoustic (Abbey Road, Studio One.) The clarity of the LSO’s own phrasing is amply defined, so why not the soloist’s? One is almost tempted to say that this performance sounds of a period other than Elgar’s or our own. At times, her Elgar sounds uncannily like Berlioz. Menuhin, in a still fabulous recording of the work, is rich with tone and plays with a large heart on his sleeve. Hahn’s remains discreetly buried somewhere beneath her ribcage. Moreover, he can be white hot in the intensity of his playing – his cadenza is a miracle of tension and time; what defines his playing as markedly superior to Hahn’s (even if, as a whole, his technique is not without its flaws) is that he makes his instrument sing in one of Elgar’s most vocal orchestral outpourings. It is Hahn’s lack of vibrato and her complete dismissal of portamento that makes her sound so ungratifying, where Menuhin is a master of both. There is no bloom or blossom to her instrument – even in the Andante, with Elgar at his most lyrical, she crushes emotiveness as if trampling through the most serene flower garden. Because of this, the movement that most comes apart in her hands, and resembles a jigsaw puzzle thrown randomly together (i.e. the picture is never quite complete), is the emotional core of the work, the final movement. The cadenza’s instilled inwardness is but gloss in Hahn’s performance, wilfully distorted by fluctuations of tempi and little more than a vehicle for virtuosity she has little need to display. Elgar described it as waking from a dream; here we are awaking from nothing quite so enchanting as that. Vaughan Williams’ evergreen, though vapid, Lark soars serenely, though again there is something about the quality of Hahn’s spindly tone that places barbed-wire like knots in the otherwise seamless spirals of the composer’s solo writing. She feels quite lost in this orchestral sky. So back to my questions which began the review, though answered in a different order. Hahn would have been wise to have taken on board the sound qualities of the violinists of the past. She has often spoken of them. The richness of tone of a Kreisler or an Elman would have repaid handsomely in the Elgar, as would the more stratospherically and figurative sound of Marie Hall in the Vaughan Williams. A failure to incorporate the past into her performances is one reason (among many) why this recording, made now at a comparatively early stage in her career, is so conspicuously lacking the qualities both works need. One can only suspect that Colin Davis himself is not happy with the results (I would have been) – at least from his soloist. His orchestra, as always, plays magnificently for him, though that is no reason to hear this disc. DG have to reflect on whether they think Hahn is the correct player on their books for works such as this. They must now find it galling that Gil Shaham, dismissed by the label some years ago, and one of today’s best exponents of the Elgar concerto, is no longer available to record it for them. One look at the front cover of the booklet to this release – and the blurred images inside of their soloist looking more like a diva than a violin player – suggests that musical substance is lacking. Elgar suffers irrevocably because of that. Marc Bridle Read more: https://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2004/Sept04/Elgar_Hahn.htm#ixzz3A1PvXriS