Logowanie

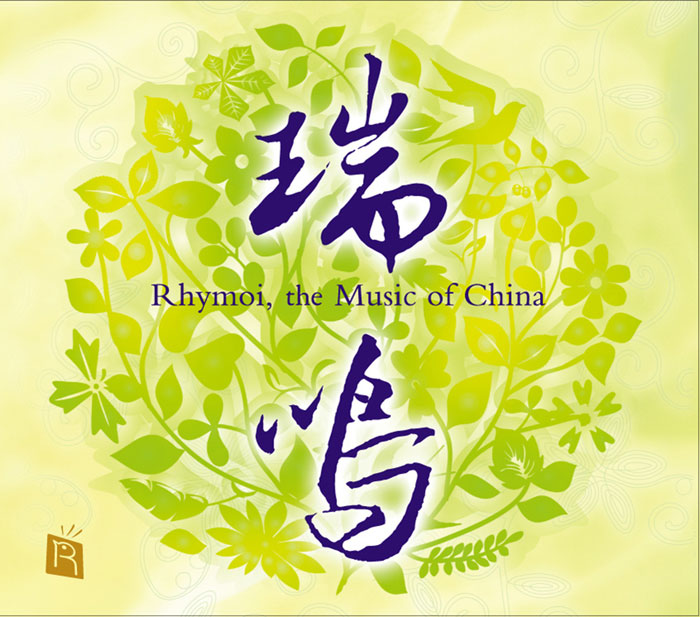

Dlaczego wszystkjie inne nie brzmią tak jak te?

Chai Lang, Fan Tao, Broadcasting Chinese Orchestra

Illusive Butterfly

Butterly - motyl - to sekret i tajemnica muzyki chińskiej.

SpeakersCorner - OSTATNIE!!!!

RAVEL, DEBUSSY, Paul Paray, Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Prelude a l'Apres-midi d'un faune / Petite Suite / Valses nobles et sentimentales / Le Tombeau de Couperin

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

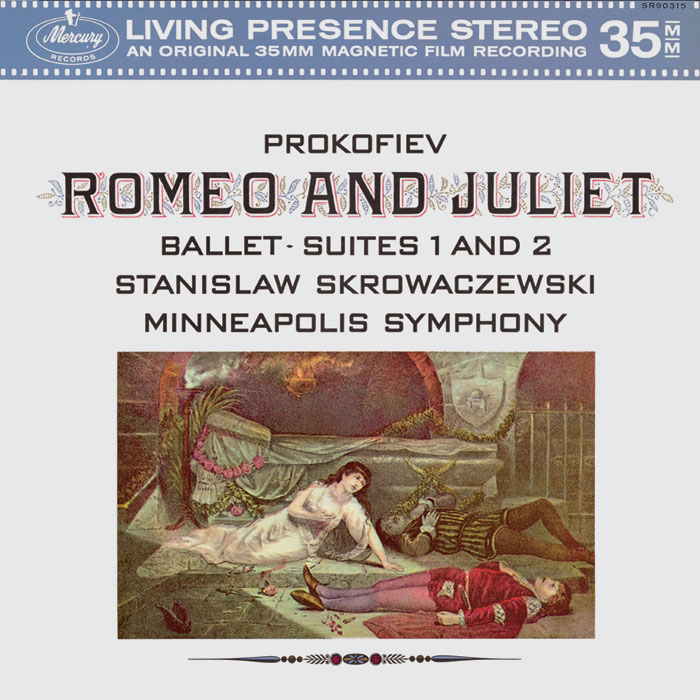

PROKOFIEV, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra

Romeo and Juliet

Stanisław Skrowaczewski,

✟ 22-02-2017

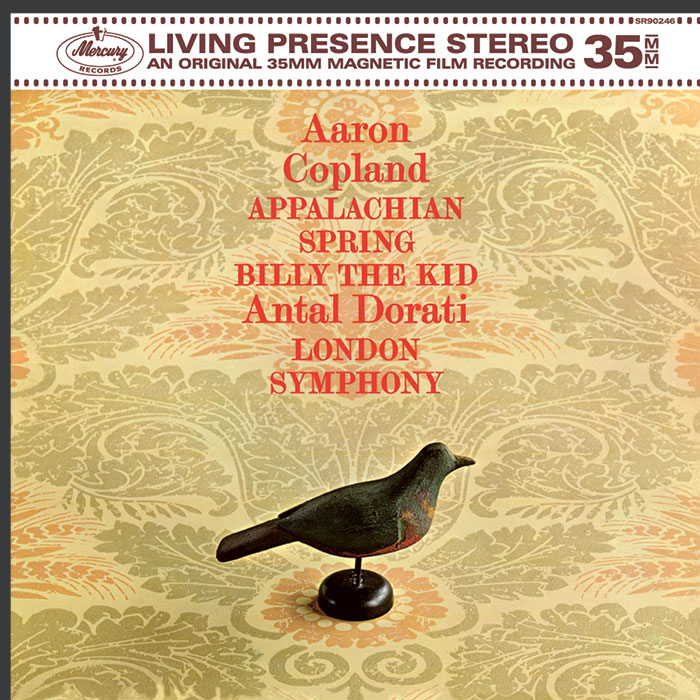

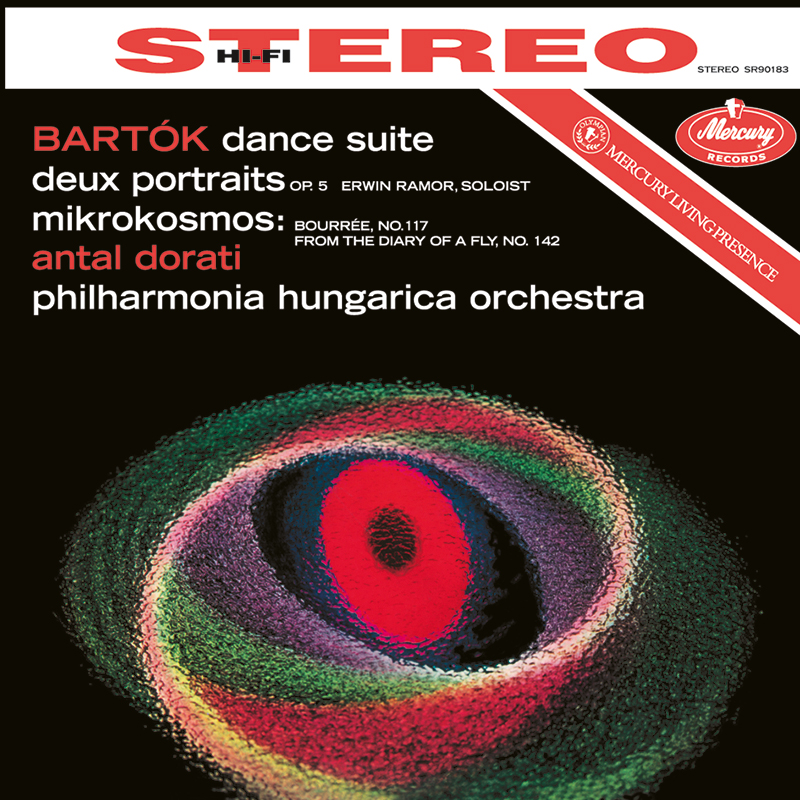

BARTOK, Antal Dorati, Philharmonia Hungarica

Dance Suite / Two Portraits / Two Excerpts From 'Mikrokosmos'

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

ENESCU, LISZT, Antal Dorati, The London Symphony Orchestra

Two Roumanian Rhapsodies / Hungarian Rhapsody Nos. 2 & 3

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Cartridge Alignment Gauge - uniwersalny przyrząd do ustawiania geometrii wkładki i ramienia

Jedyny na rynku, tak wszechstronny i właściwy do każdego typu gramofonu!

ClearAudio

Harmo-nicer - nie tylko mata gramofonowa

Najlepsze rozwiązania leżą tuż obok

IDEALNA MATA ANTYPOŚLIZGOWA I ANTYWIBRACYJNA.

Wzorcowe

Carmen Gomes

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 5 - Reference Songs

- CHCECIE TO WIERZCIE, CHCECIE - NIE WIERZCIE, ALE TO NIE JEST ZŁUDZENIE!!!

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Gregor Hamilton

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 2 - Love songs from Gregor Hamilton

...jak opanować serca bicie?...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 1 - Leonardo Amuedo

Największy romans sopranu z głębokim basem... wiosennym

Lils Mackintosh

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 4 - A Tribute to Billie Holiday

Uczennica godna swej Mistrzyni

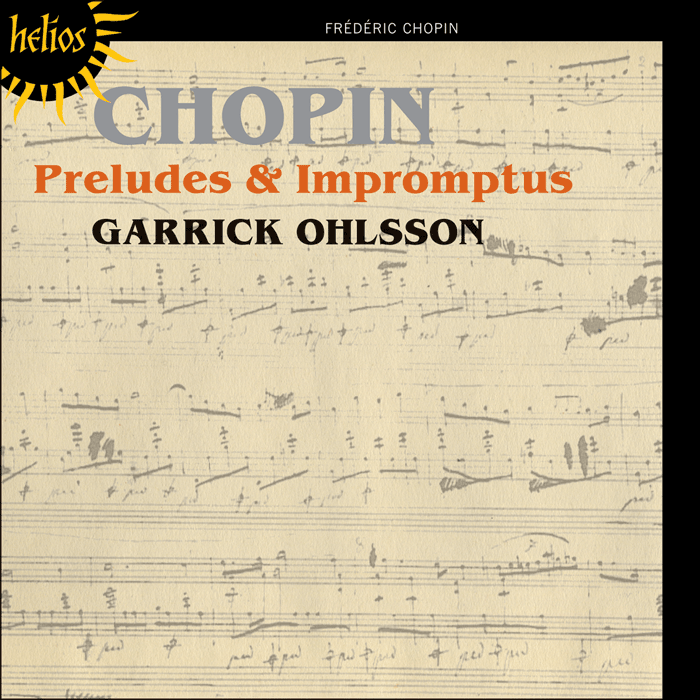

CHOPIN, Garrick Ohlsson

Preludes and Impromptus

- Twenty-Four Preludes Op. 28

- 1. No. 1 in C major Agitato

- 2. No. 2 in A minor Lento

- 3. No. 3 in G major Vivace

- 4. No. 4 in E minor Largo

- 5. No. 5 in D major Allegro molto

- 6. No. 6 in B minor Lento assai

- 7. No. 7 in A major Andantino

- 8. No. 8 in F sharp minor Molto agitato

- 9. No. 9 in E major Largo

- 10. No. 10 in C sharp minor Allegro molto

- 11. No. 11 in B major Vivace

- 12. No. 12 in G sharp minor Presto

- 13. No. 13 in F sharp major Lento

- 14. No. 14 in E flat minor Allegro

- 15. No. 15 in D flat major Sostenuto

- 16. No. 16 in B flat minor Presto con fuoco

- 17. No. 17 in A flat major Allegretto

- 18. No. 18 in F minor Allegro molto

- 19. No. 19 in E flat major Vivace

- 20. No. 20 in C minor Largo

- 21. No. 21 in B flat major Cantabile

- 22. No. 22 in G minor Molto agitato

- 23. No. 23 in F major Moderato

- 24. No. 24 in D minor Allegro appassionato

- 25. No. 14 in E flat minor (alternative tempo) Largo

- 26. Presto con leggerezza Prelude in A flat major, KKIVb/7

- 27. Prelude in C sharp minor Op. 45

- 28. Impromptu No. 1 in A flat major Op. 29

- 29. Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major Op. 36

- 30. Impromptu No. 3 in G flat major Op. 51

- 31. Fantasy Impromptu in C sharp minor Op. 66

- Garrick Ohlsson - piano

- CHOPIN

Described prosaically, Chopin’s Preludes Op 28 are a cycle of twenty-four short pieces in all the major and minor keys paired through tonal relatives (the major keys and their relative minors) progressing in the cycle of fifths. Thus the opening C major Prelude is followed by one in A minor, G major (No 3) by that in E minor (No 4), then on to D major–B minor, and so forth. Seven of them last less than a minute; only three last longer than three minutes. But it is hard to think of any piano music less deserving of such pedestrian characterization than these miniature gems, which would, on their own, have ensured Chopin’s immortality. In Bach’s time a prelude usually preceded something else, whether a fugue (as in his many organ works and the two books of the Well-Tempered Clavier) or dance movements in a suite, although Bach himself also composed short independent preludes for the keyboard. By the early nineteenth century it was common practice for pianists to improvise briefly as a prelude to their performance, an opportunity to loosen the fingers and focus the mind, and this tradition spawned several sets of Preludes encompassing all the major and minor keys, including examples from Hummel (1814), Cramer (1818), Kalkbrenner (1827), Moscheles (1827) and Kessler (1834), whose set is dedicated to Chopin. These antecedents rarely stray beyond brief technical exercises. Not for the first time, Chopin took an existing form and raised it to a new level, establishing the solo Prelude as a miniature tone poem conveying myriad emotions and moods. They in turn provided the model for the Preludes of Heller (Op 81), Alkan (Op 31), Cui (Op 64), Busoni (Op 37) and Rachmaninov (Op 3 No 2, Op 23 and Op 32), all of which also embrace all twenty-four keys. Chopin’s first essay in the genre was an independent Prelude in A flat major (composed in 1834 but not published until 1918) although not so titled by him (he gave it only a tempo indication). Here, as in several of the Op 28 Preludes, there are certain affinities with some of Bach’s Preludes, for instance the Prelude in D major from Book 1 of the Well-Tempered Clavier. However, Chopin never includes any specifically fugal or canonic passages; his counterpoint emerges as a natural part of the musical texture. In the B minor Prelude, for example, the bass serves the dual function of melodic line and harmonic support. It is noteworthy that Chopin took with him his copy of the Well-Tempered Clavier on his ill-fated trip to Majorca in 1838 with George Sand. It was here that he put the finishing touches to the cycle that had occupied him on and off since 1836. The final Prelude was completed on 22 January 1839. Some of the Preludes have attracted descriptive titles. Chopin would not have approved: none of the music is programmatic, attractive though it may be to think of the best-known of them—No 15 in D flat major, nicknamed ‘The Raindrop’—as depicting the steady drip-drip-drip of rain on the roof of their lodging in Valldemosa. No 4 in E minor and No 6 in B minor, known to all young pianists, were played on the organ at Chopin’s funeral. The tempestuous No 16 in B flat minor ranks among the most treacherous to play of all his works, while No 20 in C minor inspired two sets of variations by Busoni and one from Rachmaninov. Chopin returned to the form only once more in 1841 when he composed the Prelude in C sharp minor Op 45. The word ‘Impromptu’ comes from the French, meaning ‘improvised’ or ‘on the spur of the moment’. Its musical application is heard most famously in the short song-like works given that title by Schubert. Here, for once, Chopin alighted on a title without transforming the genre, and Schubert’s are generally better known. The first occasion he used it was for his Fantaisie-Impromptu in 1834, one of his most popular pieces and yet curiously never approved for publication (it was issued posthumously by his friend Julian Fontana in 1855 as Op 66), perhaps because it is too closely resembles Moscheles’s earlier Impromptu in E flat major Op 89. It combines the elements of ‘étude’ and ‘nocturne’ to winning effect. The famous central melody is one of Chopin’s most memorable—and in 1919 provided two American songwriters with a hit entitled ‘I’m always chasing rainbows’. Each of the three Impromptus that followed was, significantly, allotted its own opus number, like each Scherzo and Ballade. The Impromptu No 1 in A flat major Op 29 (1837) is among the most beautiful and spontaneous of all Chopin’s compositions, closely following the model of the earlier Op 66. In George du Maurier’s novel Trilby the piece becomes a talisman in the hands of Svengali, using it to hypnotize the eponymous heroine. No 2 in F sharp major Op 36 has an entirely novel structure, with its dream-like opening progressing to a march in D major and concluding with three pages of brilliant passage work. The Impromptu No 3 in G flat major Op 51 exists in two versions; it is the final form that is recorded here. It is a strange, haunting piece for which Chopin had a particular predilection—and strangeness should be, according to Edgar Allan Poe, a constituent of all great art. Jeremy Nicholas © 2010