Logowanie

Dlaczego wszystkjie inne nie brzmią tak jak te?

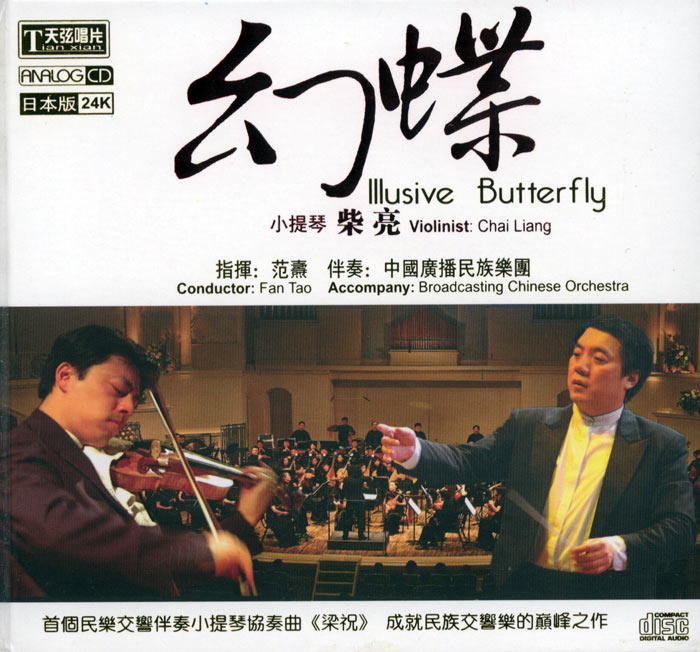

Chai Lang, Fan Tao, Broadcasting Chinese Orchestra

Illusive Butterfly

Butterly - motyl - to sekret i tajemnica muzyki chińskiej.

SpeakersCorner - OSTATNIE!!!!

RAVEL, DEBUSSY, Paul Paray, Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Prelude a l'Apres-midi d'un faune / Petite Suite / Valses nobles et sentimentales / Le Tombeau de Couperin

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

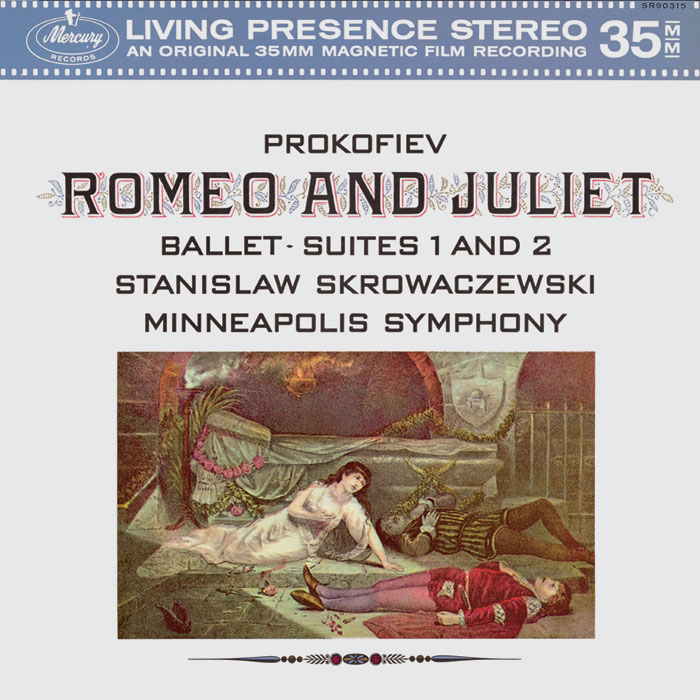

PROKOFIEV, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra

Romeo and Juliet

Stanisław Skrowaczewski,

✟ 22-02-2017

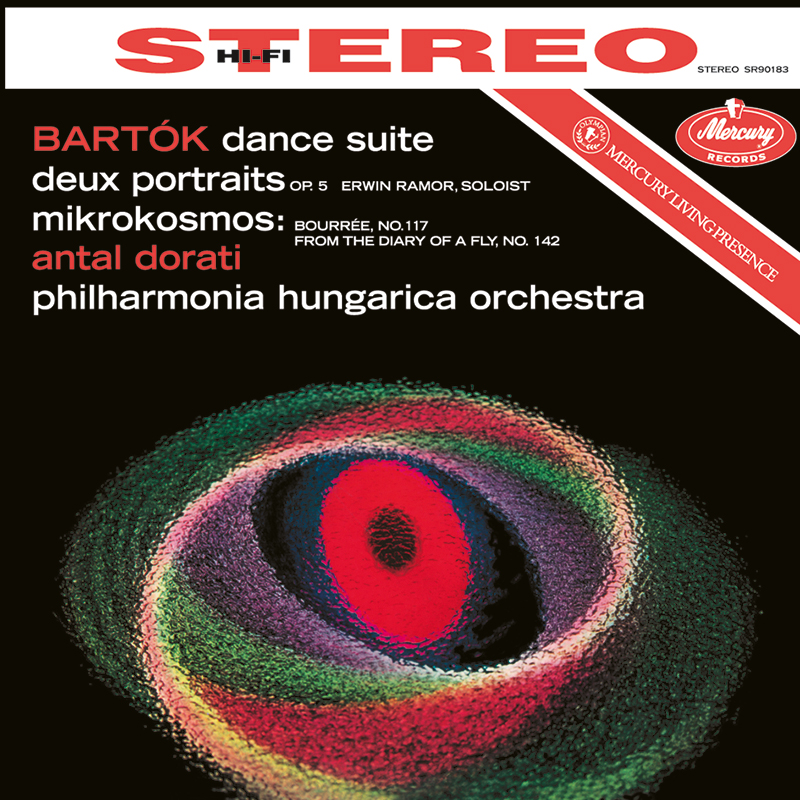

BARTOK, Antal Dorati, Philharmonia Hungarica

Dance Suite / Two Portraits / Two Excerpts From 'Mikrokosmos'

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

ENESCU, LISZT, Antal Dorati, The London Symphony Orchestra

Two Roumanian Rhapsodies / Hungarian Rhapsody Nos. 2 & 3

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

Winylowy niezbędnik

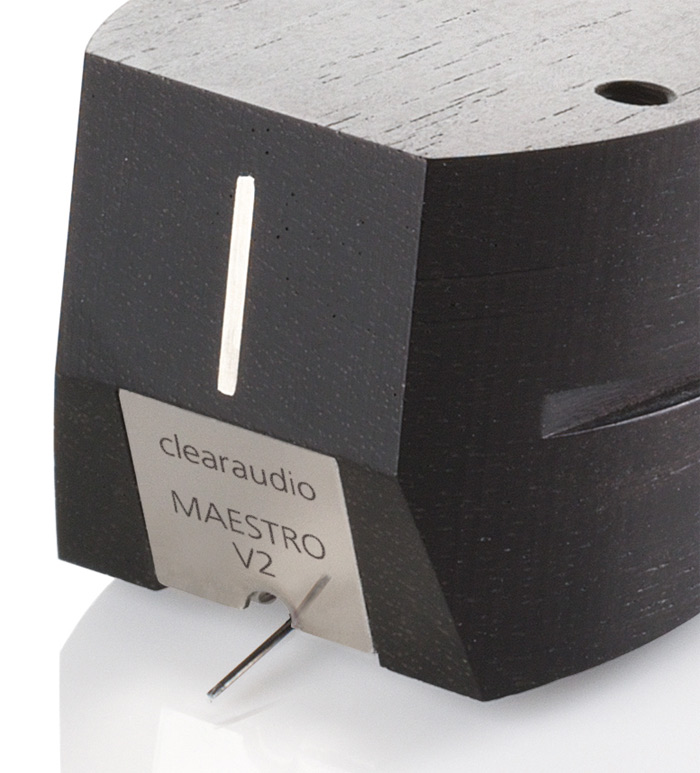

ClearAudio

Cartridge Alignment Gauge - uniwersalny przyrząd do ustawiania geometrii wkładki i ramienia

Jedyny na rynku, tak wszechstronny i właściwy do każdego typu gramofonu!

ClearAudio

Harmo-nicer - nie tylko mata gramofonowa

Najlepsze rozwiązania leżą tuż obok

IDEALNA MATA ANTYPOŚLIZGOWA I ANTYWIBRACYJNA.

Wzorcowe

Carmen Gomes

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 5 - Reference Songs

- CHCECIE TO WIERZCIE, CHCECIE - NIE WIERZCIE, ALE TO NIE JEST ZŁUDZENIE!!!

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Gregor Hamilton

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 2 - Love songs from Gregor Hamilton

...jak opanować serca bicie?...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 1 - Leonardo Amuedo

Największy romans sopranu z głębokim basem... wiosennym

Lils Mackintosh

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 4 - A Tribute to Billie Holiday

Uczennica godna swej Mistrzyni

BRAHMS, Sir Charles Mackerras, Scottisch Chamber Orchestra

Symphony No. 1 / Academic Festival Overture

Johannes Brahms - Brahms: Symphony No. 1; Academic Festival Overture

01. Symphony No.1 in C Minor, Op. 68: I. Un Poco Sustenuto - Allegro (15:33)

02. Symphony No.1 in C Minor, Op. 68: II. Andante Sostenuto (8:55)

03. Symphony No.1 in C Minor, Op. 68: III. Un Poco Allegretto E Graziso (4:16)

04. Symphony No.1 in C Minor, Op. 68: IV. Adagio - Allegro Non Troppo, Ma Con Brio (16:37)

05. Symphony No.1 in C Minor, Op. 68: II. Alternate 2Nd Movement (8:42)

06. Academic Festival Overture, Op.80 (9:46)

- Sir Charles Mackerras - conductor

- Scottisch Chamber Orchestra - orchestra

- BRAHMS

Mackerras’ highly regarded Telarc Brahms cycle bills itself as being “in the style of the original Meiningen performances.” This claim is, of course, nonsense, if only because of the word “original.” The interpretations are based on a very interesting 1933 typescript by Walter Blume, a pupil of Meiningen conductor Fritz Steinbach, which allegedly comprises the conductor’s own notes on how to interpret the four symphonies plus the Haydn Variations. Steinbach succeeded Richard Strauss in Meiningen, where he remained from 1886-1902. Strauss had followed Hans von Bülow, so calling Steinbach’s Meiningen Brahms “original” makes no sense at all. The Brahms tradition there preceded him by at least two conductors, and could have been quite different when it did.

Nevertheless, we can say that Steinbach’s notes, if accurately transcribed by Blume, represent an authentic Brahms tradition, and they are quite interesting. For one, they make it clear that Steinbach’s approach to tempo and accent was much freer than usual today. They also suggest that vibrato was already in general use. It is mentioned only twice in the typescript, in the description of the First Symphony’s introduction, and in connection with the slow movement of the Third Symphony. In both cases, Steinbach warns the orchestra not to use vibrato–specifically in order to create a special timbral effect–thereby implying that it was in pretty continuous or at least unobjectionable use otherwise. Interestingly, the note-writer for this edition of the symphonies misses that point entirely, still adhering to the usual period-instrument cant that vibrato was employed “only as an ornament” at the time in question.

The reason for bringing all of this, and these performances, up now is because Blume’s typescript, formerly extremely difficult to find (I got my copy through a German antique book-seller several years ago), has now been published in an edition edited by Michael Schwalb for Olms Verlag, as Brahms in der Meininger Tradition. If you know a bit of German, plus the usual musical terminology, the typescript itself is relatively easy to follow. Sometimes Mackerras sticks to it, and sometimes he doesn’t–which is a good thing, actually, because Mackerras was a great conductor in his own right and we don’t want or need a purely mechanical application of someone else’s rules.

However, you can glean a good example of the general approach from the coda of the Second Symphony’s finale, which is quite effective and, at the end of the day, not terribly controversial. The performances are noteworthy for their transparency, energy, and natural ensemble balances, with especially persuasive accounts of the Third and Fourth Symphonies. You also get an excellent Haydn Variations and a rousing Academic Festival Overture, plus the original version of the First Symphony’s slow movement.

The note-writer would also have us believe that Brahms preferred performances of his music with small forces. This is total nonsense. If you’re interested in a good musical education, avoid Robert Pascall and the University of Nottingham. Brahms loved larger ensembles (as scholar Styra Avins has pointed out), and as to what he preferred more generally, we may assume that he wanted the best possible quality whatever the absolute numbers in question. Nevertheless, these are fine interpretations of uncommon interest, and now, if you are curious, you can get the book on which they claim to be based and see to what extent Mackerras really does embody at least one authentic Brahms performance tradition.

-- David Hurwitz, ClassicsToday.com