Logowanie

OSTATNIE EGZEMPLARZE

Jakość LABORATORYJNA!

ORFF, Gundula Janowitz, Gerhard Stolze, Dietrich-Fischer Dieskau, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Eugen Jochum

Carmina Burana

ESOTERIC - NUMER JEDEN W ŚWIECIE AUDIOFILII I MELOMANÓW - SACD HYBR

Winylowy niezbędnik

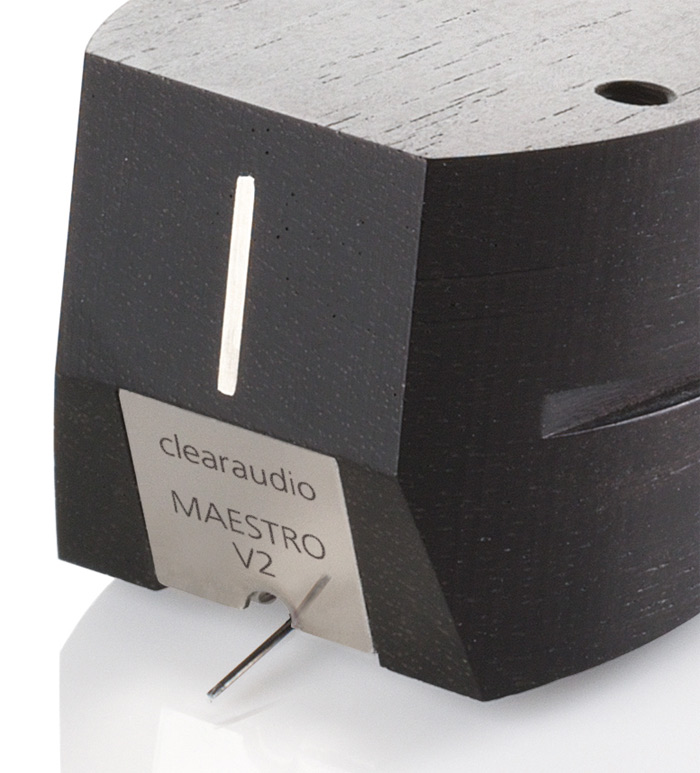

ClearAudio

Essence MC

kumulacja zoptymalizowana: najlepsze z najważniejszych i najważniejsze z najlepszych cech przetworników Clearaudio

Direct-To-Disc

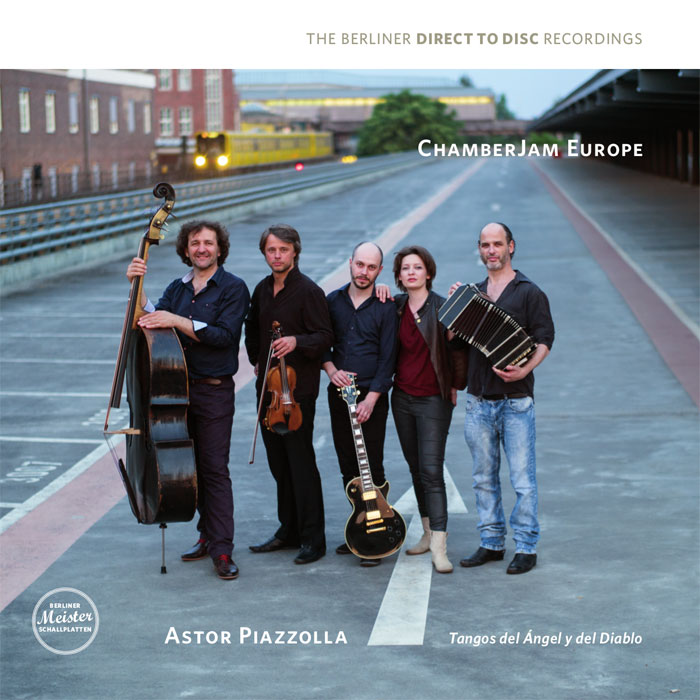

PIAZZOLLA, ChamberJam Europe

Tangos del Ángel y del Diablo

Direct-to-Disc ( D2D ) - Numbered Limited Edition

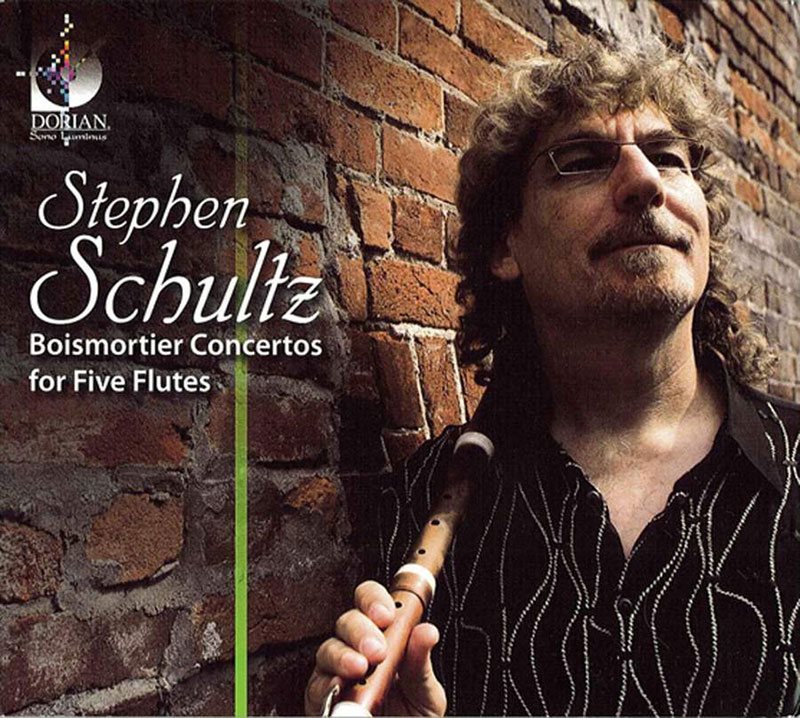

BOISMORTIER, Stephen Schultz

Concertos for Five Flutes

- Boismortier Concertos for Five Flutes

- 01. Concerto in D Major - I. Allegro (1:44)

- 02. Concerto in D Major - II. Adagio (2:49)

- 03. Concerto in D Major - III. Allegro (3:27)

- 04. Concerto in G Major - I. Adagio (2:57)

- 05. Concerto in G Major - II. Allegro (2:19)

- 06. Concerto in G Major - III. Allegro (2:34)

- 07. Concerto in a minor - I. Allegro (2:44)

- 08. Concerto in a minor - II. Largo (2:33)

- 09. Concerto in a minor - III. Allegro (2:49)

- 10. Concerto in A Major - I. Allegro (2:08)

- 11. Concerto in A Major - II. Affettuoso (2:12)

- 12. Concerto in A Major - III. Allegro (3:16)

- 13. Concerto in b minor - I. Adagio (2:34)

- 14. Concerto in b minor - II. Allegro (2:21)

- 15. Concerto in b minor - III. Allegro (3:45)

- 16. Concerto in e minor - I. Adagio (2:40)

- 17. Concerto in e minor - II. Allegro (2:36)

- 18. Concerto in e minor - III. Allegro (2:50)

- Stephen Schultz - flute

- BOISMORTIER

Here is something a little unusual. Six concerti (we'd call them sonatas now) by the French Baroque composer, Joseph Bodin de Boismortier. He was born in 1689 in Thionville and died in 1755 after spending much of his life in Paris, where his music – much of it for flute – was immensely popular. Indeed, he wrote the first French solo concerto for any instrument. These concerti, his opus 15, are amongst his most important, impressive, lively and original works. It's good to have them available in any form; although two other recordings are current: with soloists from Le Concert Spirituel (on Naxos 8.553639) and by an ensemble of five players including Barthold Kuijken (on Accent 24161). On this CD Baroque flute specialist Stephen Schultz plays all five parts. In a sonorous (slightly too reverberant, perhaps) acoustic we are taken at very close quarters through these gentle yet vibrant works. Breathiness is par for this course – the end of [tr.17], for example – ; and not intrusive. But Schultz's familiarity with, and confidence at fully interpreting, the music has us listening to its melodies and textures, harmonies and changes in speed and rhythm, not to the instrument itself. Boismortier was a prolific composer; he produced over 100 named opuses by the 1740s with at least half a dozen others which are either lost now, or cannot be accurately dated. This outpouring is to some extent reflected in his style. It is lively, vivacious, stirring and confident. But as are those of Vivaldi and Telemann. No spurious repetition or writing to a formula; or so Schultz approach has us think. There is freshness and openness throughout. Just as well, for this could be cloying repertoire. The distinction is one between capaciousness and fertility. These performances accentuate the latter at every turn. True, the unconventional scoring (five flutes!) was a risk then; it is now. But one is not tired, jaded or begging for relief at the end of these pieces. One retains the sense of intrigue and a kind of fresh satisfaction at the achievement of both composer and flutist. This is in large part because Boismortier was clearly aware of the pitfalls… the different flutes are made to have personalities, almost, and their rather gracious textures are set in relief, one to the other(s). It is Schultz's gift that he never loses the musical threading, nor ever takes a less contrasting, distinguished way out and lets the sheer sound do the work. Not that there aren't "effects". Sometimes the 'massed' flutes sound like strings; sometimes they dip their heads in Vivaldi's direction (in the finale of the G Major [tr.6], for example); at others they even play with space… alternation, polyphony between the subgroups. Still, it's the instruments as instruments, working with varying melodies that make this a successful enterprise… shifts, surprises, delays, turns about, runs ahead and behind. Generally a very pleasing set of musical lines. But – it is to be noted – without ever trivializing, or downplaying the import of the musical invention. Perhaps Boismortier is due for a revival and more serious attention outside the world of late Baroque French specialists. The flute is a modern one – by Rod Cameron (San Francisco, 1984) after Gresner (1760) and in boxwood at A=415. Its tone is rich and clear, if a little metallic in places. While not lacking depth, it may be that the sound produced presumably by overlaying five tracks produces some less than rich harmonics. Dorian is to be congratulated, too, for marketing its CDs using recycled material and providing online-only inserts; PDFs at the Dorian Website. There are some parts of this recording that bring us up short: the abrupt ending of the Allegro of the a minor and B minor concerti [trs.09,15]; and the very tightly – almost compacted – playing in unison in the affetuoso movement of the A Major and adagio of the e minor concerti [trs.11,16], for instance. But they add to our engagement, rather than distract us. So, this recording is a kind of novelty. But it's not overplayed. The substance is never lacking. The execution is brilliant yet unostentatious. Whether as something of a rarity or as a nice introduction to this corner of the very French world, this is a CD worth looking at – for a pleasing array of inventive and uncluttered indulgences in the flute. Copyright © 2008, Mark Sealey