Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

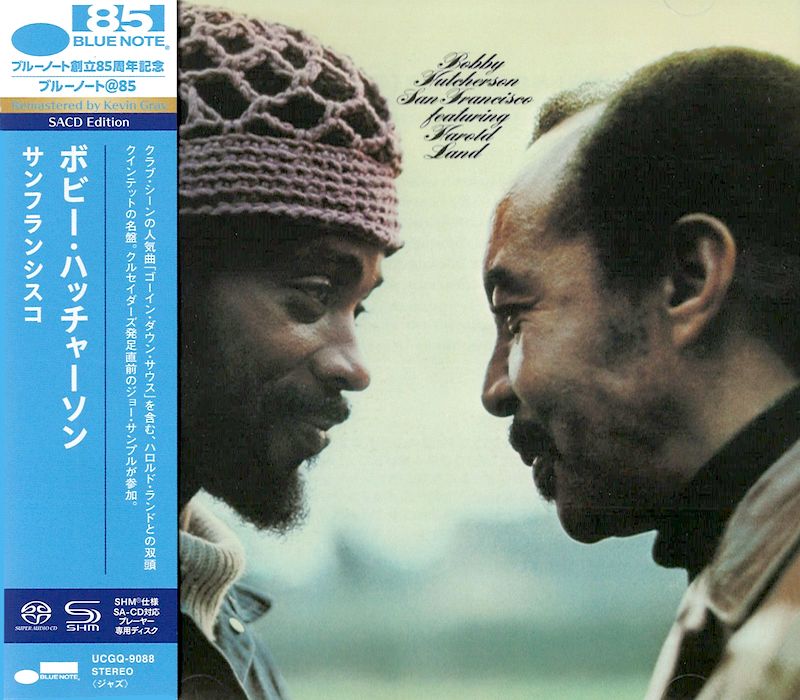

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

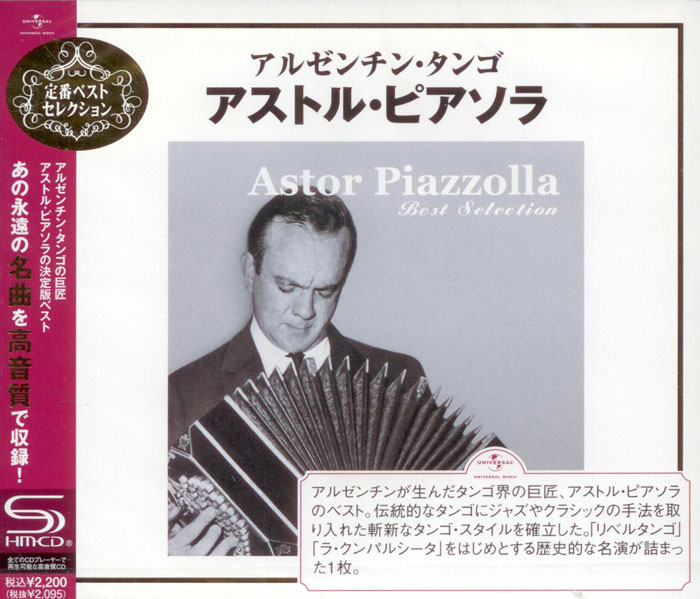

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

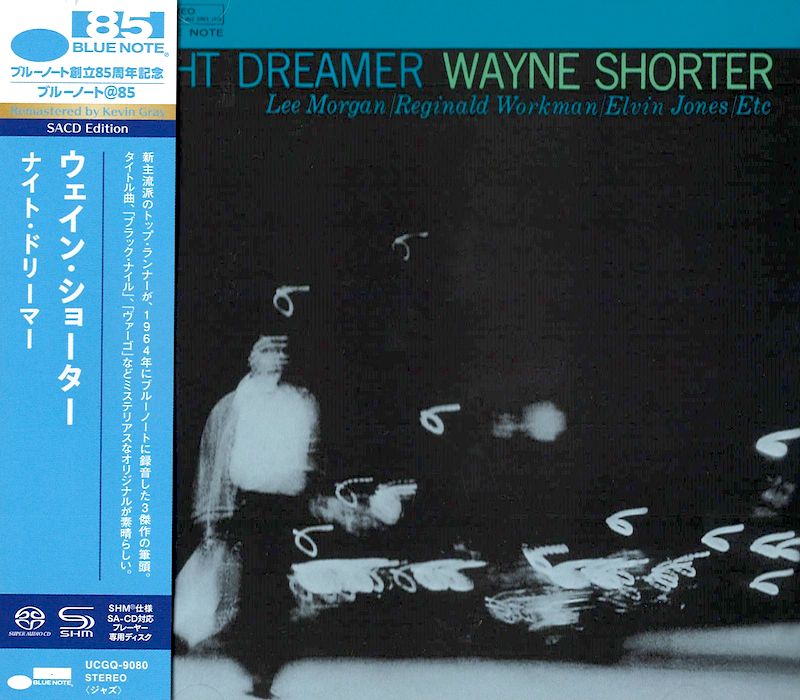

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Karnawał czas zacząć!

Music of Love - Hi-Fi Latin Rhythms

Samba : Music of Celebration

AUDIOPHILE 24BIT RECORDING AND MASTERING

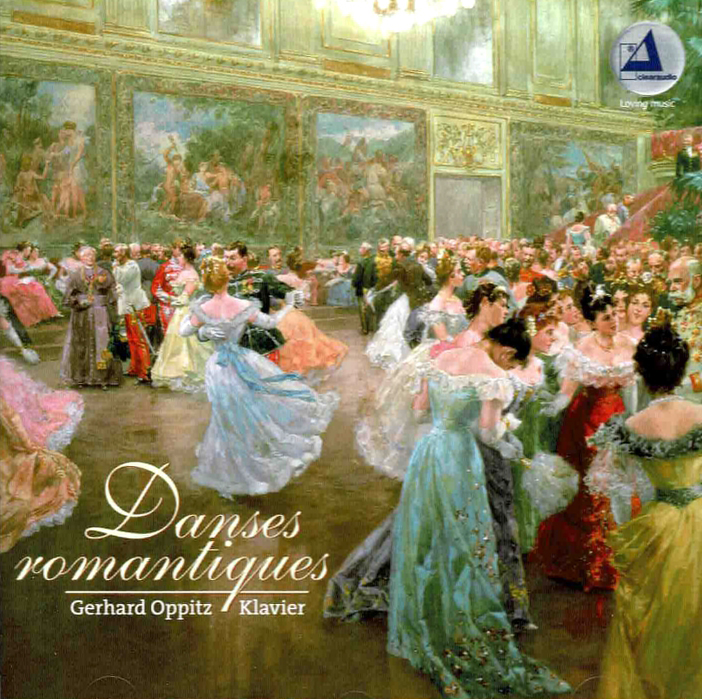

CHOPIN, LISZT, DEBUSSY, DVORAK, Gerhard Oppitz

Dances romantiques - A fantastic Notturno

Wzorcowa jakość audiofilska z Clearaudio

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

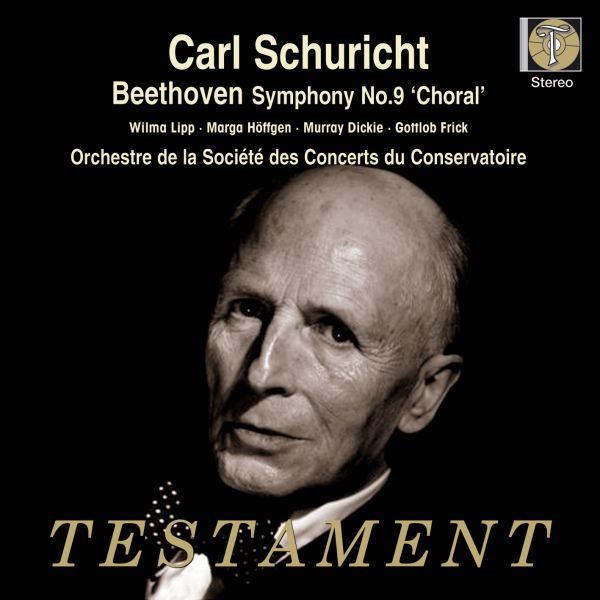

BEETHOVEN, Wilma Lipp, Elisabeth Hongen, Gottlob Frick, Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, Carl Schuricht

Symphony 9

- 1. I: Allegro Ma Non Troppo, Un Poco Maestoso

- 2. II: Molto Vivace

- 3. III: Adagio Molto E Cantabile

- 4. IV: Presto

- 5. Presto

- 6. Alla Marcia

- Wilma Lipp - soprano

- Elisabeth Hongen - mezzosopran

- Gottlob Frick - bass

- Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire - orchestra

- Carl Schuricht - conductor

- BEETHOVEN

Schuricht jest uważany za najznakomitszego niemieckiego dyrygenta czasów przed i powojennych. Jego ojciec prowadził manufakturę produkującą organy, a matka była pianistką. Nauki pobierał u takich sław jak Engelbert Humperdinck w Hochschule für Musik w Berlinie, następnie u Maxa Regera w Lipsku. Jego całe życie wypełnione było muzyką - "every Sunday in summer we used to hire three large open carriages and go out into the country. After the picnic we would join in singing choral works by Bach, Handel and Mendelssohn." Jego kariera nie przebiegała w szaleñczym tempie, ale był uwielbiany zarówno przez publiczność jak i przez członków prowadzonych przez siebie orkiestr. An important addition to the legacy of Carl Schuricht (1880-1967), especially as the original recordings derive from stereo masters from the period 27-31 May 1958. This wonderfully dramatic, fluent account is rife with especial touches in inflection and dynamic shadings from Schuricht, a master of orchestral definition who only now is receiving something like his due. Several of the vocal participants had turned in sumptuous collaboration with Jascha Horenstein for the Vox label three years prior. Take, for instance, Schuricht's acceleration of the tempo at the first trio in Scherzo, a whirlwind for horns and strings, with tripping figures and lovely interweaving of the oboe solo. The thoroughly improvisatory, groping quality of the first movement, too, attests to a spiritual attempt to take inchoate masses of sound and congeal them into a visceral entity of magnificent power. I find the Paris players extremely responsive to agogic shifts in the Scherzo, still without losing any of the cumulative momentum that shakes the hands off the clock. The coda snaps one back to earth, only so that the pursuant Adagio molto e cantabile can take us to the places Mahler, Scriabin, and Bruckner wished to inhabit. Positive comparisons with Furtwaengler's layered approach to the Ninth are inevitable, not only in terms of pacing and phraseology, but for the broad humanity of the performance. Exemplary work in the flute and French horn. Testament has divided the last movement into three sections, two Prestos and the Alla Marcia. A sudden thrust into the first declamation and orchestral recitative, then a quick survey of the prior motifs. The orchestral melos treats the materials as an overture rife with arias from the ensuing vocal parts. Schuricht's style lies between Furtwaengler's German pensiveness and Toscanini's liquid, driven long-view. Gottlob Frick's warm invocation to dismiss abstract tones in favor of human ones ushers forth lovely responses from the Elisabeth Brasseur Choir, celebrated in its time for its excellent ensemble. Wilma Lipp's soprano part soars along with the flute, and the frenzy of joy erupts in full, dizzying force. Janizzary figures of the first order, and a Murray Dickie who sounds a bit like Wagner's Mime. The high sopranos at "Seid umschlungen" invoke our own "Himmel hoch." The preparation for the mysteries of the fugue is as subtle as the power of the contrapunctus itself. Impressive on all counts, a real addition to the great readings of the Ninth Symphony. (Gary Lemco