Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

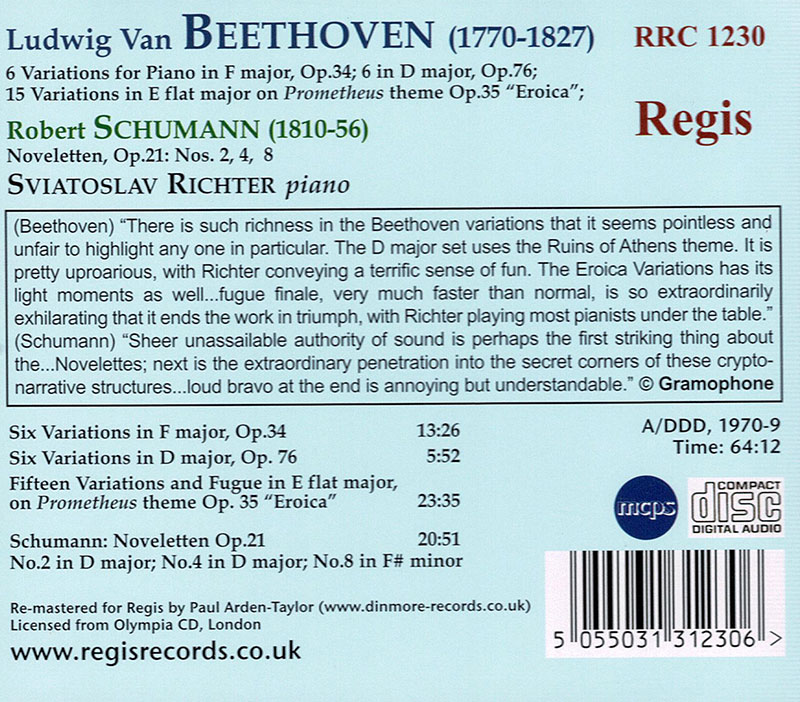

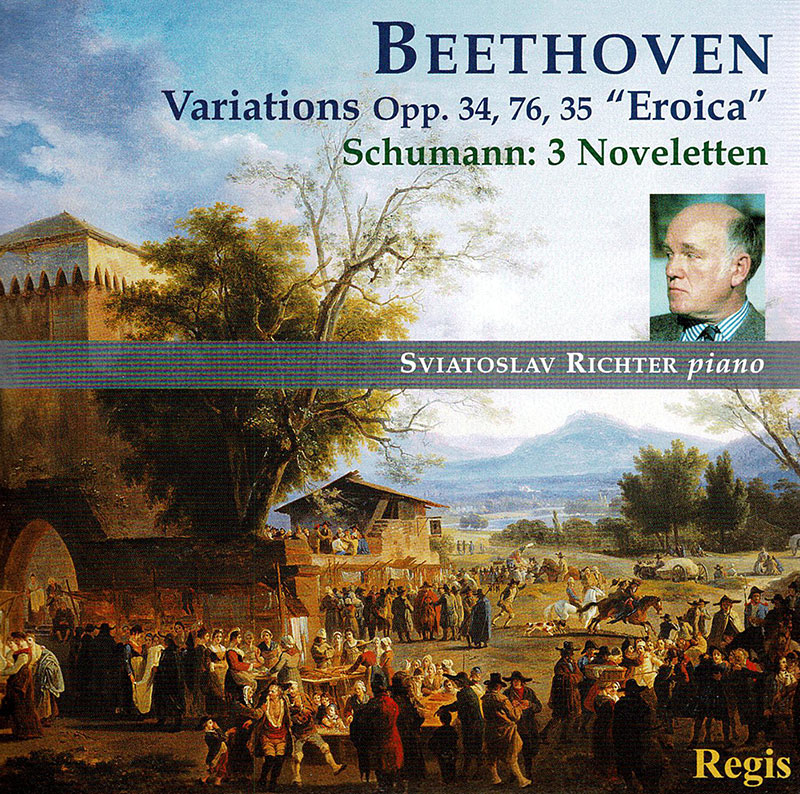

BEETHOVEN, SCHUMANN, Sviatoslav Richter

Six Variations in F major, in D major, in E flat major / Novelletten op.21

- Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

- Six Variations in F major op.34 [13:26],

- Six Variations in D major op.76 [05:52],

- Fifteen Variations and Fugue in E flat major op.35 – “Eroica” [23:35]

- Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

- Novelletten op.21:

- no.2 in D [05:56],

- no.4 in D [03:27],

- no.8 in F sharp minor [11:37]

- Sviatoslav Richter - piano

- BEETHOVEN

- SCHUMANN

Richter continues to pour in from all sides. To Regis we owe the reinstatement of the studio recordings the pianist made for Ariola Eurodisc around 1970. We have already had Bach, Chopin and Schumann - all reviewed by me with the utmost enthusiasm - now it is the turn of Beethoven. As on other occasions, they have filled up the CD - the original LP was somewhat meagre in timing even for those days - with some live performances recorded in Japan, though in all truth even the Beethoven variations alone would have been worth far more than the asking price. Come to think of it, just the six minutes of the D major variations on their own would have been worth it. If I make a particular point of these it is because this set, based on the famous “Ruins of Athens” march, is usually dismissed as one of Beethoven’s pieces of rubbish and is only played, dutifully, by pianists who are booked to record all the variations and so can’t get out of it. How typical of Richter to turn his attention to something like this – and yet how maddening that we are thus deprived of his interpretation of the far greater C minor variations which most pianists choose to make a triptych with opp. 34 and 35. He doesn’t try to turn the work into profound Beethoven, he just pitches in with such a kick to his rhythm that you want to get up and dance. We have to face the fact that, though it might not have looked that way, somewhere inside himself Richter had a great sense of humour and he realizes that this music is real fun if you treat it as an uproarious knees-up. His playing of the 6th variation, where Beethoven forgets to keep to the shape of his original theme and extends himself like a cat chasing its own tail, is a miracle of no-holds-barred rising energy. James Murray’s notes tell us that these three sets of variations entered Richter’s repertoire in 1949/50. Unfortunately, the only alternative recordings listed in the Richter discography are all live versions made in the run-up period to this particular recording so, unless new material emerges, we will not be able to compare the pianist’s interpretations at other stages in his career. I am rapidly reaching the conclusion, however, that Richter reached his absolute zenith around the time of these Ariola Eurodisc recordings, his early virtuoso flair undimmed yet combined with the wisdom of full maturity, a wisdom which could later verge on the didactic. The sheer fact that he had been playing all three works for some twenty years gives him a considerable edge over Schnabel’s pioneering recording of op.34, for this work had not figured largely in Schnabel’s repertoire. I felt that Schnabel was uncharacteristically slow and cautious in, for example, the second variation, and here is Richter proving the point with a touch of Schumannesque whimsy. Richter in his turn may seem a little slow in the 4th and 5th variations – marked respectively “Tempo di Menuetto” and “Marcia – Allegretto” – but the ongoing rhythm he transmits is remarkable and I am reminded that he actually played for the ballet in his very earliest days. He exudes a great sense of enjoyment as he swings into the 6th (Allegretto) variation. I must be a Beckmesser and point out that he halves the tempo for the last four bars, but I can’t help wondering whether Beethoven himself had not slipped up with his notation. What Richter does certainly sounds logical and convincing and this ending would sound rather odd if played literally. Schnabel is in truly Promethean form in op.35, and yet it has to be said that it does make a difference if the listener can just sit back in the complete confidence that, no matter what technical hurdles Beethoven will throw in the pianist’s way, they will be conquered as if they didn’t exist. Again, enjoyment is the key. Schnabel perhaps tries to relate the work to the “Eroica” symphony finale based on the same theme. Richter remembers that the “Eroica” symphony did not yet exist. When the innocent little contredanse theme arrives he gives it a delightful Austrian lilt at a slower tempo than conductors usually choose for the symphony, and then we’re off! This is Beethoven the young firebrand rebel; variations 9 and 13 are outrageous pieces of telling people where to go, and again I must emphasize the humour. Hear how he makes the pause in variation 3 a little bit longer the second time round and then lets fly; and listen to the last two notes of variation 7! While in the last pages Schnabel almost convinces us that this is the “Eroica” symphony, Richter makes no attempt to inflate it, concluding jubilantly but without heroics. In the Schumann we may marvel at the sheer clarity of Richter’s texture, as well as his surging romanticism and, again, humour. Rubinstein had a gentler way with no.2, but he, like Richter, was choosy about the “Novelletten” he played, limiting himself to the first two. Both prove that you can be romantic without wallowing in a sea of pedal. The 8th Novellette is like a cycle of pieces within the cycle and here Richter is at his most masterly, charting unerringly its quicksilver changes of mood. The recordings were not quite state-of-the-art for their day – the Beethoven is a bit shallow – but are no obstacle to enjoyment. The Schumann recordings are obviously professional jobs, presumably by a radio station. Enthusiastically recommended – and a reminder that Regis also offer Richter recordings of the Diabelli Variations and a trio of Sonatas. There is a divergence of opinion within the accompanying material as to whether “Novelletten” has one or two “L”s. The Henle edition has two and, is it was printed in Germany, I presume they know what they’re doing. The German language corrector in Word 2003 gives it as an error either way! Christopher Howell