Logowanie

Dlaczego wszystkjie inne nie brzmią tak jak te?

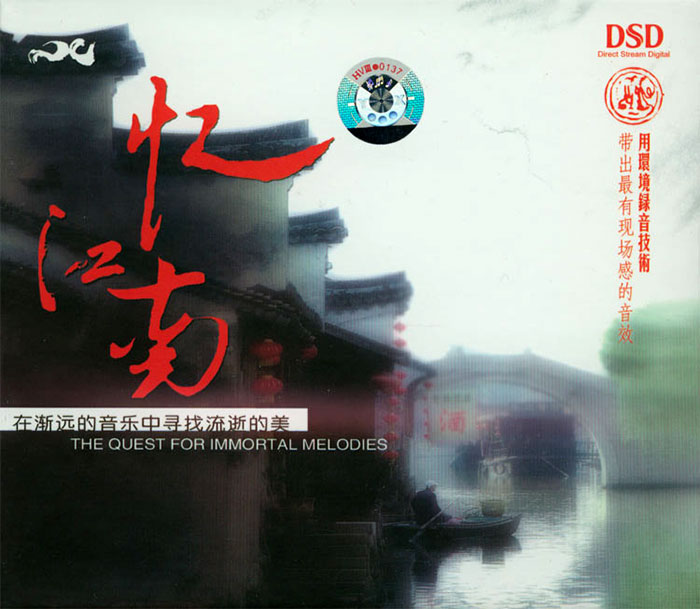

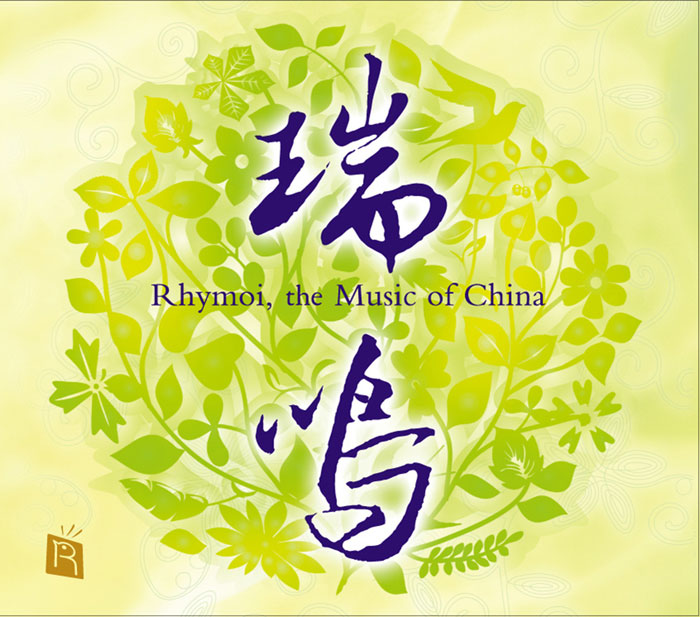

Chai Lang, Fan Tao, Broadcasting Chinese Orchestra

Illusive Butterfly

Butterly - motyl - to sekret i tajemnica muzyki chińskiej.

SpeakersCorner - OSTATNIE!!!!

RAVEL, DEBUSSY, Paul Paray, Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Prelude a l'Apres-midi d'un faune / Petite Suite / Valses nobles et sentimentales / Le Tombeau de Couperin

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

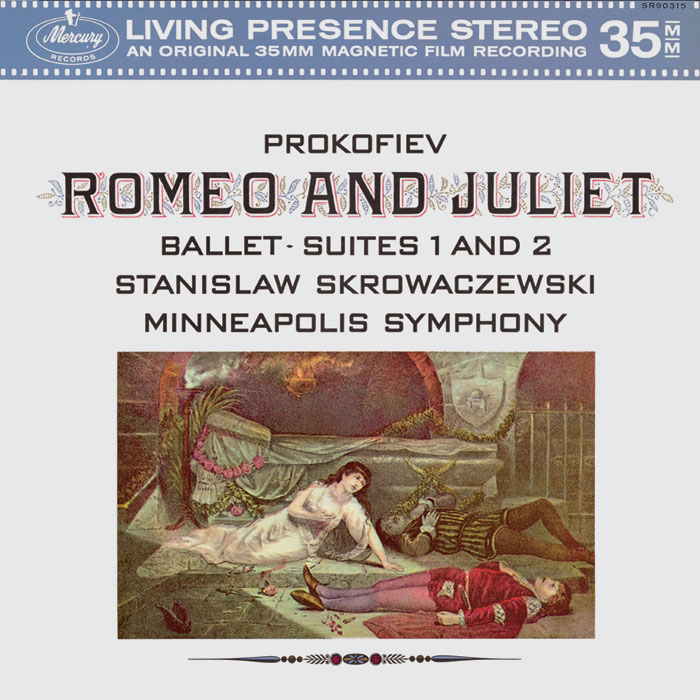

PROKOFIEV, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra

Romeo and Juliet

Stanisław Skrowaczewski,

✟ 22-02-2017

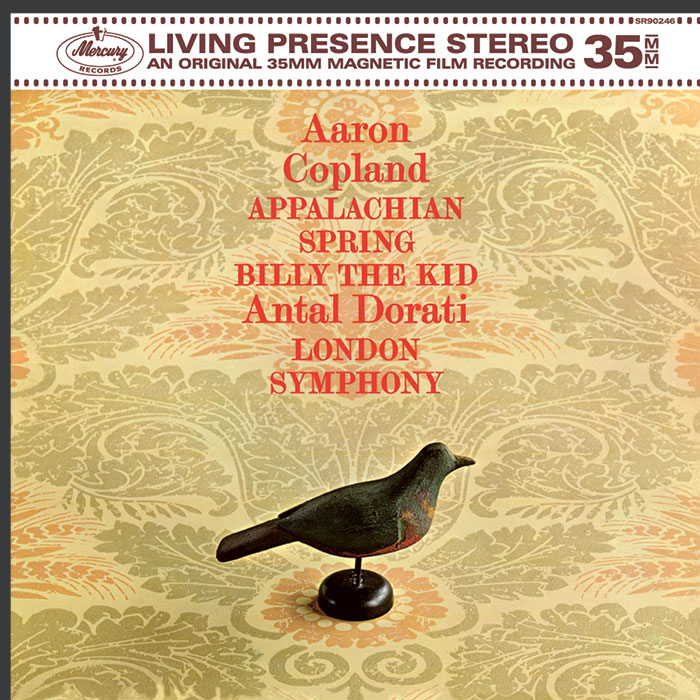

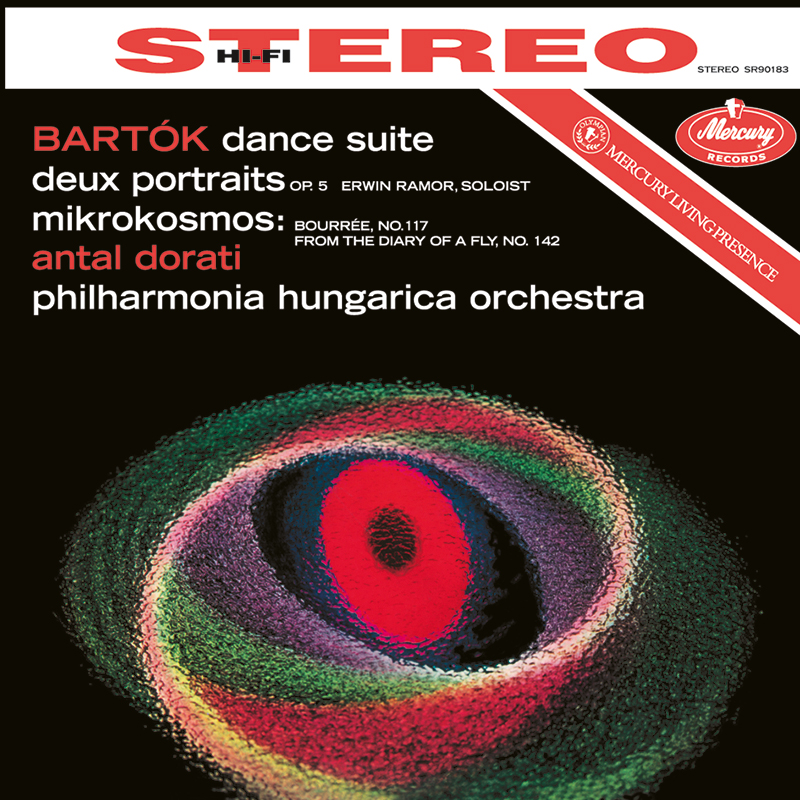

BARTOK, Antal Dorati, Philharmonia Hungarica

Dance Suite / Two Portraits / Two Excerpts From 'Mikrokosmos'

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

ENESCU, LISZT, Antal Dorati, The London Symphony Orchestra

Two Roumanian Rhapsodies / Hungarian Rhapsody Nos. 2 & 3

Samozapłon gwarantowany - Himalaje sztuki audiofilskiej

Winylowy niezbędnik

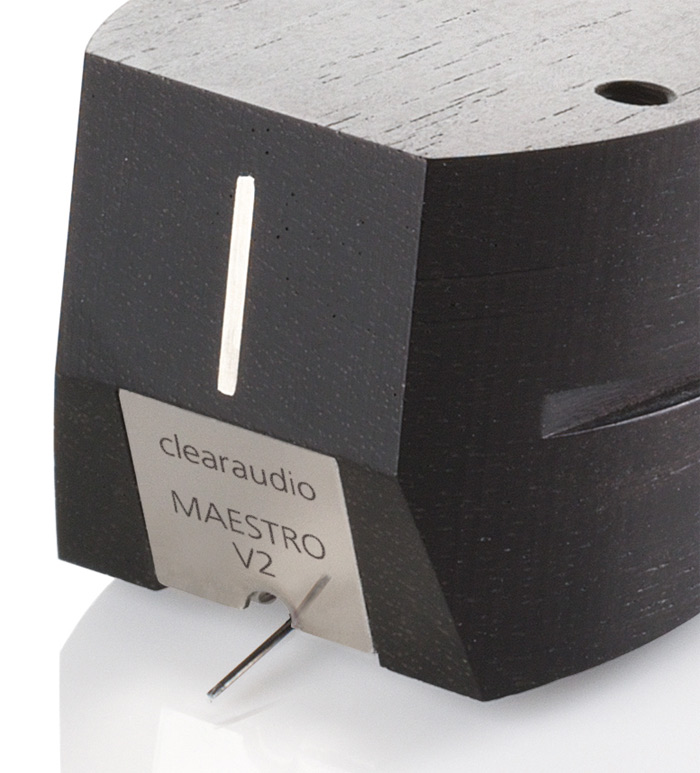

ClearAudio

Cartridge Alignment Gauge - uniwersalny przyrząd do ustawiania geometrii wkładki i ramienia

Jedyny na rynku, tak wszechstronny i właściwy do każdego typu gramofonu!

ClearAudio

Harmo-nicer - nie tylko mata gramofonowa

Najlepsze rozwiązania leżą tuż obok

IDEALNA MATA ANTYPOŚLIZGOWA I ANTYWIBRACYJNA.

Wzorcowe

Carmen Gomes

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 5 - Reference Songs

- CHCECIE TO WIERZCIE, CHCECIE - NIE WIERZCIE, ALE TO NIE JEST ZŁUDZENIE!!!

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Gregor Hamilton

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 2 - Love songs from Gregor Hamilton

...jak opanować serca bicie?...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 1 - Leonardo Amuedo

Największy romans sopranu z głębokim basem... wiosennym

Lils Mackintosh

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 4 - A Tribute to Billie Holiday

Uczennica godna swej Mistrzyni

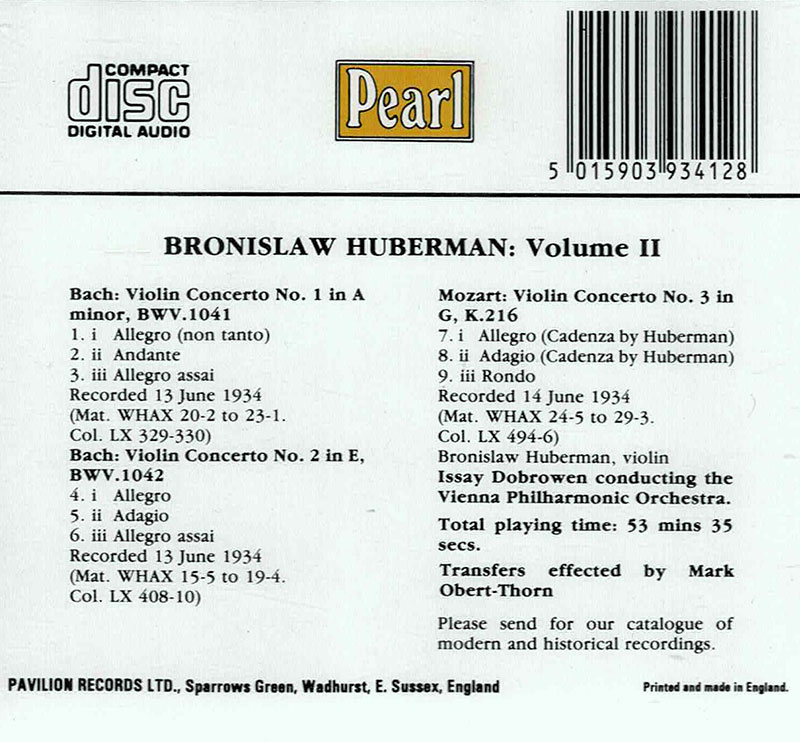

BACH, MOZART, Bronislaw Huberman, Vienna Philharmonic, Issay Dobrowen

Violin Concerto No.1 in A minor / Violin Concerto No.2 in E / Violin Concerto No.3 in G

- Bronislaw Huberman - violin

- Vienna Philharmonic - orchestra

- Issay Dobrowen - conductor

- BACH

- MOZART

madamemusico 5,0 von 5 SternenIndispensable for Huberman fans 10. November 2003 - Veröffentlicht auf Amazon.com Bronislaw Huberman was one of the most versatile, emotive and exciting violinists who ever lived. Despite the fact that he was a Polish Jew, he was often described as having the "soul of a gypsy," meaning that he played with the same emotion and fire as a Rrom fiddler, though he had the technique for and knowledge of classical music. The results were performances unlike any others, combining a sharp spiccato attack with portamento slides and a variance of tone color from dry, edgy sounds to the most sumptuous vibrato. Such a technique was indeed closely related, not only to Gypsy violinists, but also to Klezmer musicians who Huberman would have had first-hand knowledge of. (Similar techniques were also introduced to jazz by Italian-American violinist Joe Venuti.) These recordings of Bach and Mozart violin concerti are fascinating side-looks at a section of his repertoire that one would not think within his scope. But this is only because, in our time, we play this music much more chastely, "respecting" the "composer's wishes" by scrupulously observing written directions but adding nothing of ourselves. Such performance practices, in my view, reduce the vitality and interest of great music to the level of computer-generated sounds-no more, no less. Oddly enough, Huberman's performances here are very close in tempo and overall design to those recorded by historically-informed violinist-conductor Sigiswald Kuijken, one of the more emotionally interesting of modern performers. In his recorded performances of 1984, a full 50 years after Huberman's, Kuijken displays almost exactly the same tempi (which are a shade slower than most modern versions), a similar balance among the upper strings (though there are less of them...Kuijken's "La Petite Bande" uses only 12 strings, of which two are basses, whereas Issay Dobrowen and the Vienna Philharmonic members use at least twice that number, of which five or six appear to be basses), and similar phrasing. The differences lie in texture and attack. In Kuijken's versions, the solo violinist "emerges" from the massed strings to take his solos against the ensemble backdrop which then recedes slightly in volume to let him be heard, while Huberman always plays as soloist-with-orchestra, the Vienna strings occasionally becoming quite soft so that his tone can stand out from them. But Huberman was no egoist, and so there are moments even here when he falls back to play a couple of ensemble passages with the massed strings, acting in these moments as section leader rather than soloist. And of course, though both Kuijken and Huberman play with a relatively "straight," vibratoless tone, Kuijken does not employ the slides and dips that were such a feature of Huberman's style. Curiously, these stylistic anachronisms of Huberman's seem less annoying than simply different. His artistic integrity was such that the mere thought of his doing them to impose personal glory or "individualism" is quite out of the question. His intent was always to enhance the music, never himself. Huberman's tone is drier and his phrasing a shade quirkier in the Mozart Concerto No. 3, yet even here he makes his points through the way he phrases and accents the music rather than through unnecessary histrionics. I find his approach different but interesting, rather like Lilli Lehmann's Mozart rather than like Emma Eames'. Indeed, his phrasing of the languorous second movement reminded me quite strongly of Lehmann's recording of the duet from "Nozze di Figaro" with her niece, Hedwig Helbig. Your decision as to whether to purchase this disk or not will, of course, depend on your willingness to accept non-traditional readings of these works, but in my view everything Huberman recorded is of supreme interest.