Logowanie

OSTATNIE EGZEMPLARZE

Jakość LABORATORYJNA!

ORFF, Gundula Janowitz, Gerhard Stolze, Dietrich-Fischer Dieskau, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Eugen Jochum

Carmina Burana

ESOTERIC - NUMER JEDEN W ŚWIECIE AUDIOFILII I MELOMANÓW - SACD HYBR

Winylowy niezbędnik

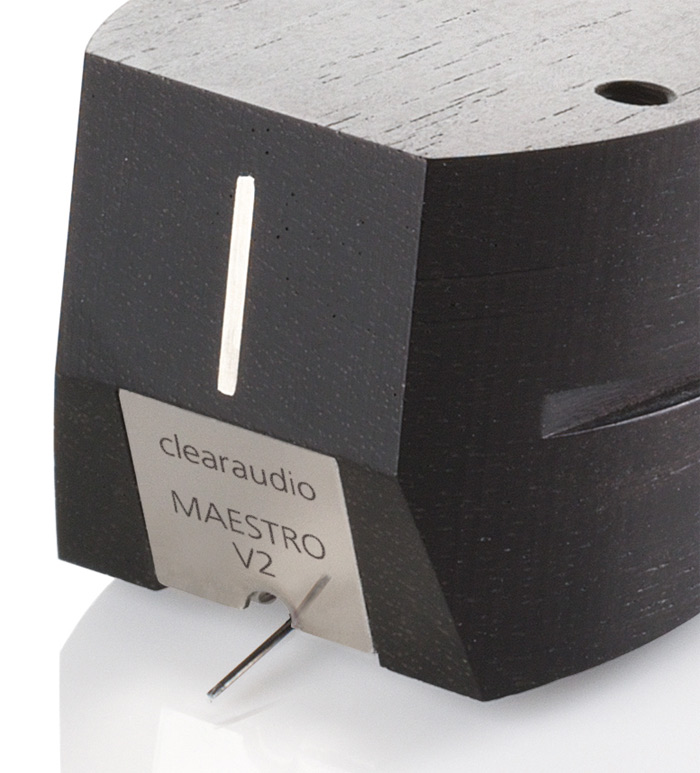

ClearAudio

Essence MC

kumulacja zoptymalizowana: najlepsze z najważniejszych i najważniejsze z najlepszych cech przetworników Clearaudio

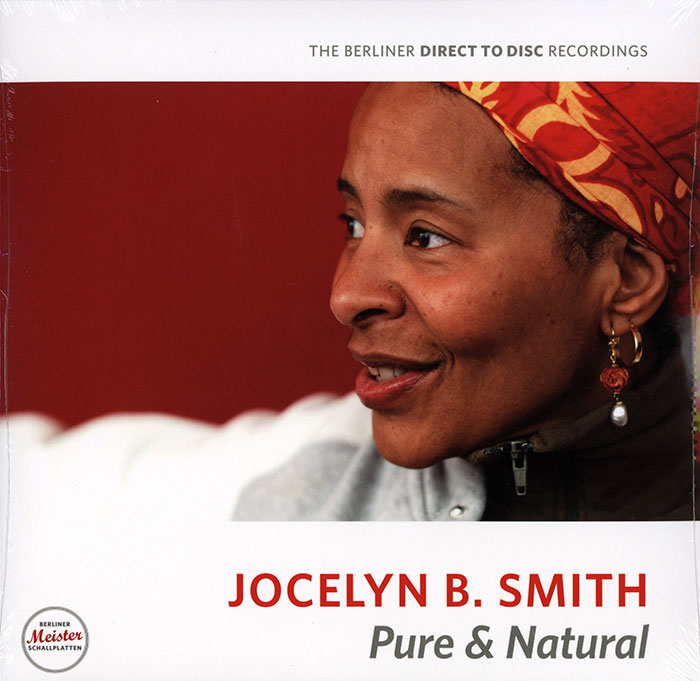

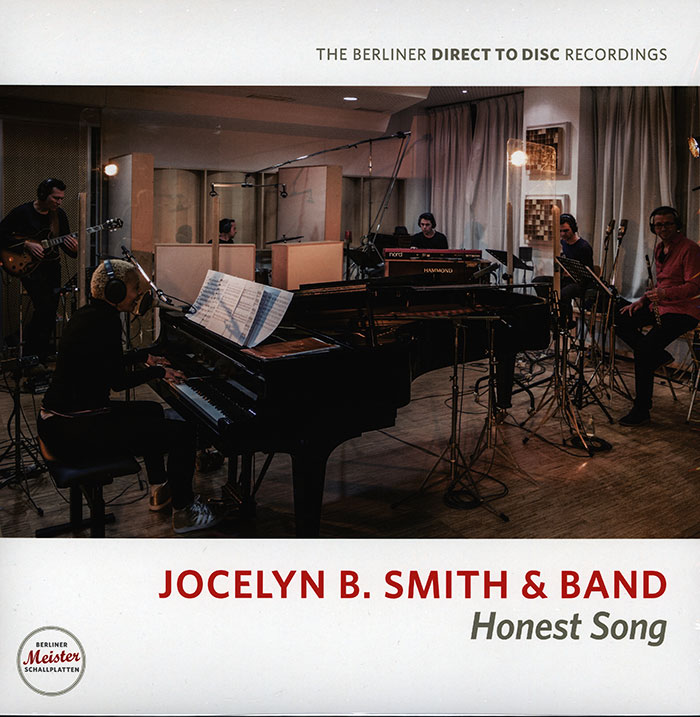

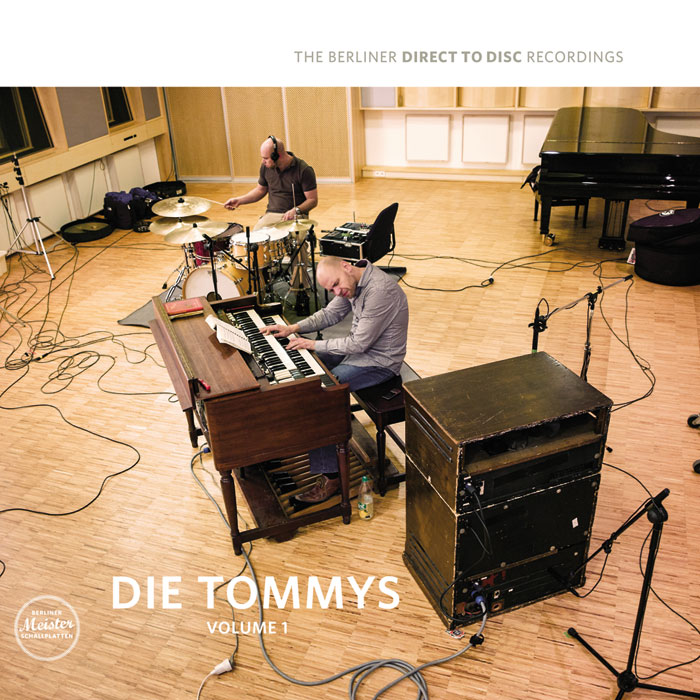

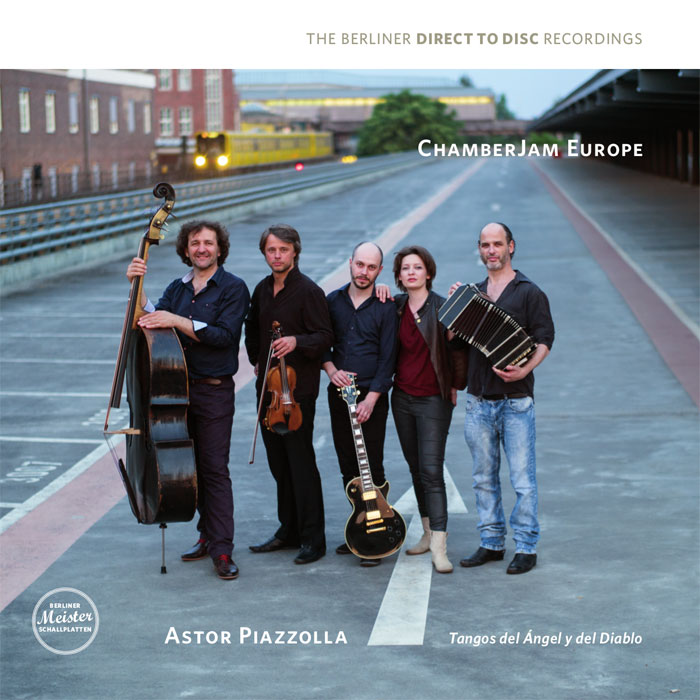

Direct-To-Disc

PIAZZOLLA, ChamberJam Europe

Tangos del Ángel y del Diablo

Direct-to-Disc ( D2D ) - Numbered Limited Edition

BACH, Angela Hewitt

Das wohltemperirte Clavier - Book 1

- Das wohltemperirte Klavier 'The well-tempered Clavier' Book 1, BWV846-869

- CD1

- 1 No 01 in C major, BWV846. Movement 1: Prelude [2:08]

- 2 No 01 in C major, BWV846. Movement 2: Fugue [1:56]

- 3 No 02 in C minor, BWV847. Movement 1: Prelude [1:31]

- 4 No 02 in C minor, BWV847. Movement 2: Fugue [1:45]

- 5 No 03 in C sharp major, BWV848. Movement 1: Prelude [1:24]

- 6 No 03 in C sharp major, BWV848. Movement 2: Fugue [2:14]

- 7 No 04 in C sharp minor, BWV849. Movement 1: Prelude [2:31]

- 8 No 04 in C sharp minor, BWV849. Movement 2: Fugue [5:27]

- 9 No 05 in D major, BWV850. Movement 1: Prelude [1:21]

- 10 No 05 in D major, BWV850. Movement 2: Fugue [2:09]

- 11 No 06 in D minor, BWV851. Movement 1: Prelude [1:42]

- 12 No 06 in D minor, BWV851. Movement 2: Fugue [2:34]

- 13 No 07 in E flat major, BWV852. Movement 1: Prelude [3:34]

- 14 No 07 in E flat major, BWV852. Movement 2: Fugue [1:42]

- 15 No 08 in E flat minor, BWV853. Movement 1: Prelude [3:40]

- 16 No 08 in E flat minor, BWV853. Movement 2: Fugue [5:36]

- 17 No 09 in E major, BWV854. Movement 1: Prelude [1:27]

- 18 No 09 in E major, BWV854. Movement 2: Fugue [1:07]

- 19 No 10 in E minor, BWV855. Movement 1: Prelude [2:19]

- 20 No 10 in E minor, BWV855. Movement 2: Fugue [1:10]

- 21 No 11 in F major, BWV856. Movement 1: Prelude [1:02]

- 22 No 11 in F major, BWV856. Movement 2: Fugue [1:35]

- 23 No 12 in F minor, BWV857. Movement 1: Prelude [1:52]

- 24 No 12 in F minor, BWV857. Movement 2: Fugue [4:38]

- CD2 1 No 13 in F sharp major, BWV858. Movement 1: Prelude [1:30]

- 2 No 13 in F sharp major, BWV858. Movement 2: Fugue [2:19]

- 3 No 14 in F sharp minor, BWV859. Movement 1: Prelude [1:01]

- 4 No 14 in F sharp minor, BWV859. Movement 2: Fugue [3:17]

- 5 No 15 in G major, BWV860. Movement 1: Prelude [0:55]

- 6 No 15 in G major, BWV860. Movement 2: Fugue [2:59]

- 7 No 16 in G minor, BWV861. Movement 1: Prelude [2:03]

- 8 No 16 in G minor, BWV861. Movement 2: Fugue [1:45]

- 9 No 17 in A flat major, BWV862. Movement 1: Prelude [1:25]

- 10 No 17 in A flat major, BWV862. Movement 2: Fugue [3:06]

- 11 No 18 in G sharp minor, BWV863. Movement 1: Prelude [1:29]

- 12 No 18 in G sharp minor, BWV863. Movement 2: Fugue [2:22]

- 13 No 19 in A major, BWV864. Movement 1: Prelude [1:27]

- 14 No 19 in A major, BWV864. Movement 2: Fugue [2:00]

- 15 No 20 in A minor, BWV865. Movement 1: Prelude [1:02]

- 16 No 20 in A minor, BWV865. Movement 2: Fugue [5:38]

- 17 No 21 in B flat major, BWV866. Movement 1: Prelude [1:20]

- 18 No 21 in B flat major, BWV866. Movement 2: Fugue [1:50]

- 19 No 22 in B flat minor, BWV867. Movement 1: Prelude [4:02]

- 20 No 22 in B flat minor, BWV867. Movement 2: Fugue [3:10]

- 21 No 23 in B major, BWV868. Movement 1: Prelude [1:03]

- 22 No 23 in B major, BWV868. Movement 2: Fugue [2:24]

- 23 No 24 in B minor, BWV869. Movement 1: Prelude [4:47]

- 24 No 24 in B minor, BWV869. Movement 2: Fugue [6:49]

- Angela Hewitt - piano

- BACH

The six years that Johann Sebastian Bach spent as Capellmeister to Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen (1717-1723) were some of the happiest of his life. The young prince (only twenty-three years old in 1717) was a viola da gamba player of great skill and had an eighteen-piece orchestra of excellent calibre. Bach was delighted to work for someone who both 'loved and understood music'. On taking up his new duties, Bach relinquished the composition of organ and choral music that had occupied him previously in Weimar. Only a few cantatas were composed to celebrate royal birthdays and special occasions. Cöthen was in Saxony where Calvinism predominated at the time, and there was little music in the local churches (with the exception of the Lutheran Agnuskirche where Bach worshipped and went to practise the organ). He was now expected to produce secular instrumental music, and he did so, as was his custom, with great energy and all his heart and soul. From the Cöthen period date the Brandenburg Concertos, the four orchestral Suites, the Partitas, Suites, and Sonatas for solo and accompanied violin and cello, and the French Suites for keyboard. Bach and the prince became close friends, and he often accompanied the latter on his journeys. Upon returning from a trip to Karlsbad in 1720, Bach was confounded by the news that his wife, Maria Barbara, had died and was already buried. With four children ranging from the age of five to twelve to bring up, he could not remain a widower for long, and within a year had married Anna Magdalena Wilcke (other spellings of her name being Wilcken, Wölcken, Wülcke, or Wülcken), sixteen years his junior and a fine soprano. Their marriage was celebrated on 3 December 1721 with four barrels and thirty-two carafes of wine- almost a hundred litres! As his duties at court were not totally time-consuming, Bach was able to devote himself to the musical education of his family. In 1720, when his eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann was nine years old, he presented him with a notebook in which they began to compile pieces that contain, among other things, first drafts of what we know today as the Little Preludes, the Two- and Three-Part Inventions, and eleven of the first twelve Preludes from The Well-Tempered Clavier. It was always Bach's aim to develop musical intelligence from the very beginning along with technique- something which is often overlooked today. Many of the pieces in the Clavierbüchlein are in Wilhelm Friedemann's own hand, as he was undoubtedly learning how to compose. It is impossible to give exact dates of composition of many of Bach's works, as they were often compiled from already-existing material. In the case of The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, Bach wrote the date of 1722 on the title page of the fair copy: The Well-Tempered Clavier or Preludes and Fugues through all the tones and semitones including those with a major third or Ut Re Mi as well as those with a minor third or Re Mi Fa. For the profit and use of musical youth desirous of learning and especially for the pastime of those already skilled in this study composed and prepared by Johann Sebastian Bach at present Capellmeister to His Serene Highness the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen, and director of His Chamber Music. Anno 1722 To satisfactorily explain the adjective 'well-tempered' is to tread on dangerous ground. Treatises have been written on the subject, and even today the debate continues. Tuning a keyboard instrument always has to be a compromise, because the intervals of a perfect fifth and a perfect third are incompatible with each other and with a pure octave. In Bach's day, the common practise was to use the meantone system, which retained the purity and sweetness of the major third. This meant, however, that it was impossible to play in all twenty-four keys because of 'errors' that would occur in the more remote ones. As musicians became more and more dissatisfied with these restrictions, they turned to equal temperament which favours the interval of a perfect fifth, and which makes each key tolerable (although inevitably one can argue that much is lost by making everything uniform, especially as regards the character of each key). In between these two systems there can be many modifications, and it is thought that Bach must have used his own method of tuning. The only, rather vague, testimony we have on the subject comes from his obituary, written by his son CPE Bach and his pupil JF Agricola, where it states that: 'In the tuning of harpsichords he achieved so correct and pure a temperament that all the keys sounded pure and agreeable. He knew no keys which, because of impure intonation, one must avoid.' In 1715 Johann Caspar Fischer had composed a set of preludes and fugues in twenty different keys called Ariadne Musica. Four years later, Johann Mattheson wrote a user's manual in figured-bass playing that gave two examples in each of the twenty-four keys. It was left to Bach, however, to give us the first real music in keys like Csharp major and Eflat minor. Twenty-two years later, in 1744, he compiled another twenty-four preludes and fugues to complete what is now known as 'The 48'. It is an inexhaustible treasure trove of the greatest possible music, combining contrapuntal wizardry with his immense gift for expressing human emotion in all its forms. Bach amazes us by absolutely never running out of steam. In The Well-Tempered Clavier, we find a piece to suit every mood and every occasion. In Bach's time the word 'clavier' did not denote any keyboard instrument in particular but meant either harpsichord, clavichord, spinet, virginal, or even the organ. An inventory taken at the time of his death lists many different instruments, but gives no details beyond their size and value. Bach reportedly preferred the clavichord for its ability to produce shadings and even vibrato, although surely its extreme delicacy must have made anything but the quietest pieces rather frustrating. Perhaps for this reason, Bach's friend, the great organ and harpsichord builder Gottfried Silbermann, set about working on a fortepiano (following the first attempt at one by Cristofori) which Bach tried before his death. It is said that he found it interesting, but weak in the high register and too hard to play (complaints often voiced by pianists today about some modern grands!). His music requires great sprightliness, clarity, rapidity, warmth, strength, and subtle shadings that have to be matched by both instrument and player. If Bach's music sounds 'wrong' on the piano, then surely most of the blame must lie with the pianist. The instrument itself is, I find, ideal as it can be made to sing and dance as Bach demands. The difficulty is in making it sound easy. What does playing a prelude and fugue mean to a pianist these days? For most piano students it is a necessary part of an exam or an international piano competition- to be got through as best one can and, hopefully, without going wrong! Often they are approached too soon- long before a good grounding is established in the easier pieces of Bach. It is impossible to play a four- or five-voice fugue if you cannot already play cleanly in two or three voices. For many teachers it is perplexing, as Bach never wrote any tempo or expression marks in the score, and edited versions give conflicting opinions. For professional performers it is a great test of their abilities (and nerves!). Many prefer to play Bach transcriptions (by Liszt or Busoni, for instance) where it is easier to hide behind more notes and add the sustaining pedal. Artur Schnabel, one of the great pianists of the twentieth century, preferred not to perform The Well-Tempered Clavier in concert halls because he considered it too intimate. To become familiar with the complete '48' is to discover the endless variety within them where no two preludes are alike, and every fugue is constructed in a different fashion. The Well-Tempered Clavier has never ceased to be a source of inspiration, fascination and wonderment to professional musicians and music lovers. We have been told many times that, after his death, Bach's music fell out of favour and that it was only 'revived' by Mendelssohn. That is partly true, of course, but Mendelssohn was introduced to it by his teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter, who himself had been a pupil of Johann Kirnberger, who in turn was a pupil of Bach. Zelter, the director of the Berlin Singakademie, counted among his friends the poet Goethe who often heard the young Mendelssohn performing Bach's Fugues. Late in his life, Goethe made the following remark: It was when my mind was in a state of perfect composure and free from external distractions, that I obtained the true impress of your grand master. I said to myself: it was as if the eternal harmony was conversing within itself, as it may have done in the bosom of God, just before the creation of the world. Angela Hewitt ©1998