Logowanie

Mikołaj - ten to ma gest!

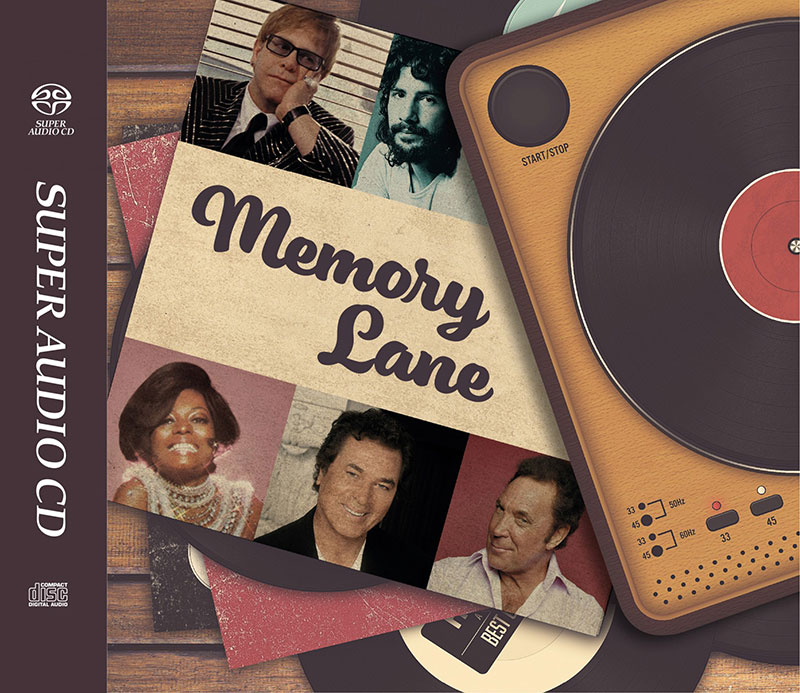

Elton John, The Mamas & The Papas, Cat Stevens, Rod Stewart, Bobbie Gentry, Stevie Wonder, Engelbert Humperdinck

Memory Lane

Edycja Numerowana - 1000 egzemplarzy w skali światowej

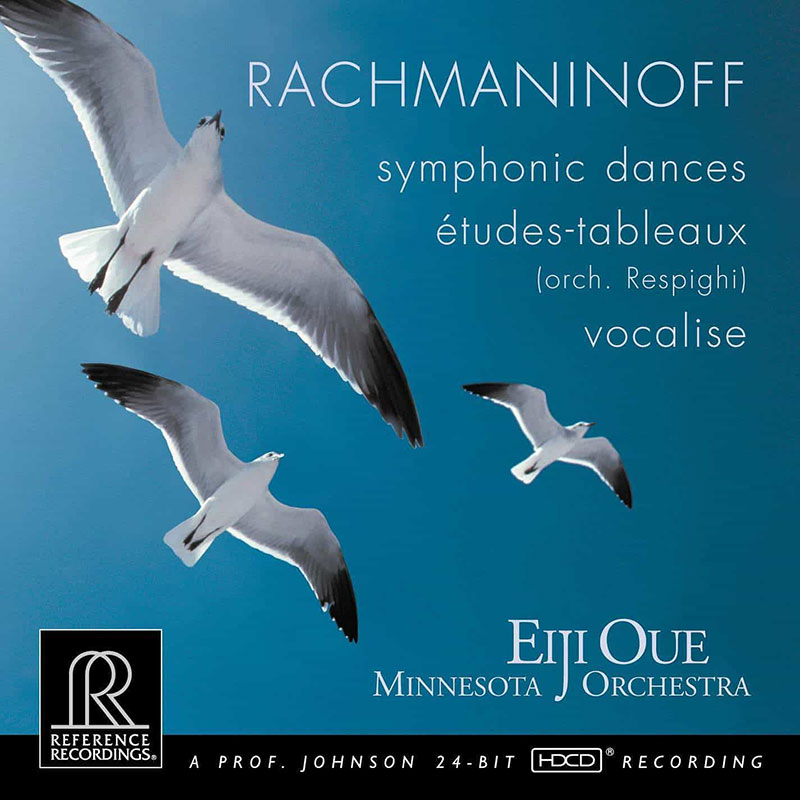

RACHMANINOV, Eiji Oue, Minnesota Orchestra

Symphonic Dances / Vocalise

Best Recordings of 2001!!! NAJCZĘŚCIEJ KUPOWANA PŁYTA Z RR!

Karnawał czas zacząć!

Music of Love - Hi-Fi Latin Rhythms

Samba : Music of Celebration

AUDIOPHILE 24BIT RECORDING AND MASTERING

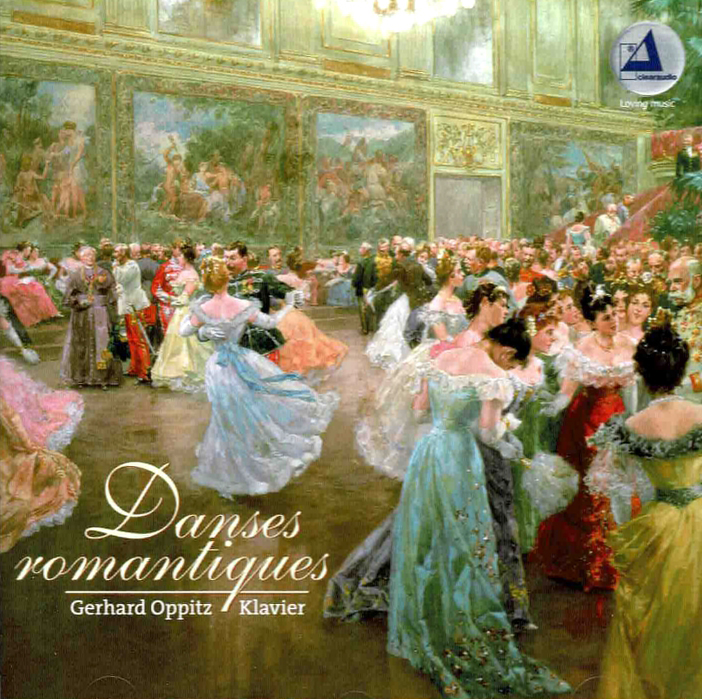

CHOPIN, LISZT, DEBUSSY, DVORAK, Gerhard Oppitz

Dances romantiques - A fantastic Notturno

Wzorcowa jakość audiofilska z Clearaudio

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

ALFANO, Magda Olivero, Giuseppe Gismondo, Mario del Monaco, Orchestra e Coro della Scala di Milano, Elio Boncompagni

Risurrezione

Wanda Dimita (Mezzo Soprano), Anna di Stasio (Mezzo Soprano), Fernanda Cadoni (Mezzo Soprano), Maya Sunara (Mezzo Soprano), Nucci Condo (Mezzo Soprano), Vito Susca (Bass), Egidio Casolari (Bass), Marco Stefanoni (Bass), Andrea Petrassi (Baritone), Maria Grazia Allegri (Mezzo Soprano), Giuseppina Milardi (Soprano), Giuseppe Gismondo (Tenor), Magda Olivero (Soprano), Antonio Boyer (Baritone), Giuseppe Scalco (Tenor) Conductor: Elio Boncompagni Italian Radio Symphony Orchestra Turin It is always dangerous when an opera is indissolubly associated with the name of one singer because, as all the melomaniacs around the world know, this makes you forget that the opera actually belongs primarily to the composer and makes the most stubborn fans to reject all the interpretations by other performers. Despite this, I dare to say that if we still remember that Franco Alfano, a composer better known for having written the finale of Turandot after Puccini’s death, has also composed an opera after Leo Tolstoy’s novel Resurrection is chiefly due to the performances of Magda Olivero. This happens for two reasons: the first is that the soprano was a great admirer of Verismo (intending “Verismo” in the widest meaning of the term) to the point that, when she was already in her nineties and did not sing on stage anymore, she picked up the pen to write an introduction to a biography on Alfano, who she personally knew. The second reason is – more banally – that few recordings of Risurrezione are available. Adding that this opera is not frequently performed on stage, we have necessarily to rely upon the material at our disposal. This last point is rather ironical as Olivero has been usually neglected by the recording industry and her career is immortalized for the major part thanks to “pirate” amateurs. So, this recording of Risurrezione is not only one of the few of the opera, but also one of the few of the singer. Olivero’s first performance of Risurrezione dates back to 1937. She studied it with Martha Alfano, the composer’s wife, and her performance was such that the composer himself wrote to his friend and colleague Umberto Giordano that «rarely an author can find a collaborator more diligent, more admirable, more enthusiastic. She “lives” the role she performs, she lives it and she “suffers” it!» The present recording is not that of the performance to which these words refers, but it is interesting to read them because the same opinion can be applied to the more mature Olivero that in 1971, at the age of sixty-one, recorded live Risurrezione with Giuseppe Gismondo and Anna Di Stasio among the singers and under the conduction of Elio Boncompagni. The recording sound is not perfect although good, the orchestral colours suffer for it and also the singers’ voices are less audible than in more recent recordings and even in recordings of the same time. This little defect is not enough to prevent Olivero’s voice to emerge and you have the impression that she sings with all her heart from her first note. Her voice has not a pure timbre, a remark made by every commentator of her so that once she said that she heard so many times that her voice was not beautiful that in the end she believed it herself. Despite and maybe exactly because of this irremediable flaw, her performance is heartfelt and she resorts to every nuance to give life to the character of the lost woman Katiusha. It is always incredible how Olivero’s not precious voice is moving, flexible and skilled in the performance of diminuendi and mezzevoci. Moreover, Olivero is an actress as well as a singer and, even if this recording does not allow to see her acting, her voice allows the listener to imagine her on stage thanks to the importance she gives to every word. I personally think that her best moment is the second act, the most tragic of the four, where her performance is more dramatic than ever. Her outbursts trouble who listens to her because here (but also in the love scene from the first act and in the final “resurrection”) she completely reveals Katiusha’s soul. Olivero’s performance is so accurate and enthralling because she makes possible an immediate comprehension of this little performed opera even to someone who did never heard a note written by Alfano before. It is not wrong to say then that Olivero is not only a singer, but also a remarkable communicator. Olivero is the real heroine of Risurrezione because Katiusha is virtually omnipresent on stage, but her colleagues form a circle around her, beginning with Giuseppe Gismondo as Dimitri, the lover who later leaves Katiusha and that in the end offers her to go back to a condition that she did not want anymore. Gismondo is overall a fine singer and does not lack a nice timbre and expressive voice, but sometimes he is imprecise and his intonation is not accurate, while his high register is a little short. The other singers have smaller roles, but it is worth remembering at least Anna Di Stasio as Matrena and as a good specialist of minor roles. Boncompagni’s conduction is permeated by dramatic tension that is particularly gripping in the second act, but overall his ideas are scanty and his conduction is not the first thing that comes to someone’s mind when thinking about this Risurrezione. It is possible anyway that the recording technique is partially responsible for this and, despite the conduction is not exceptional, it is correct and carefully follows the singers.