Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

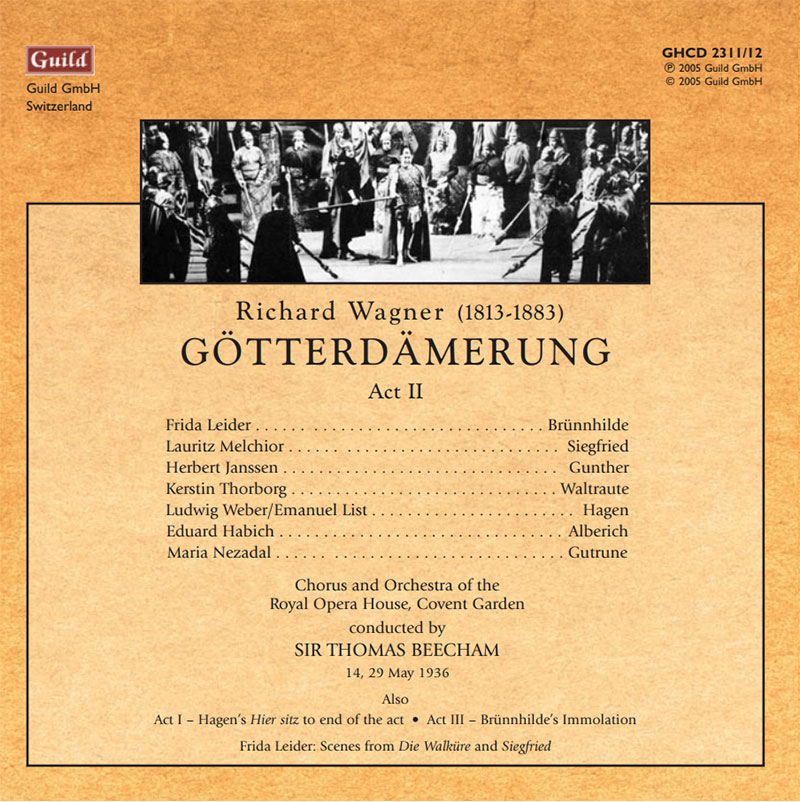

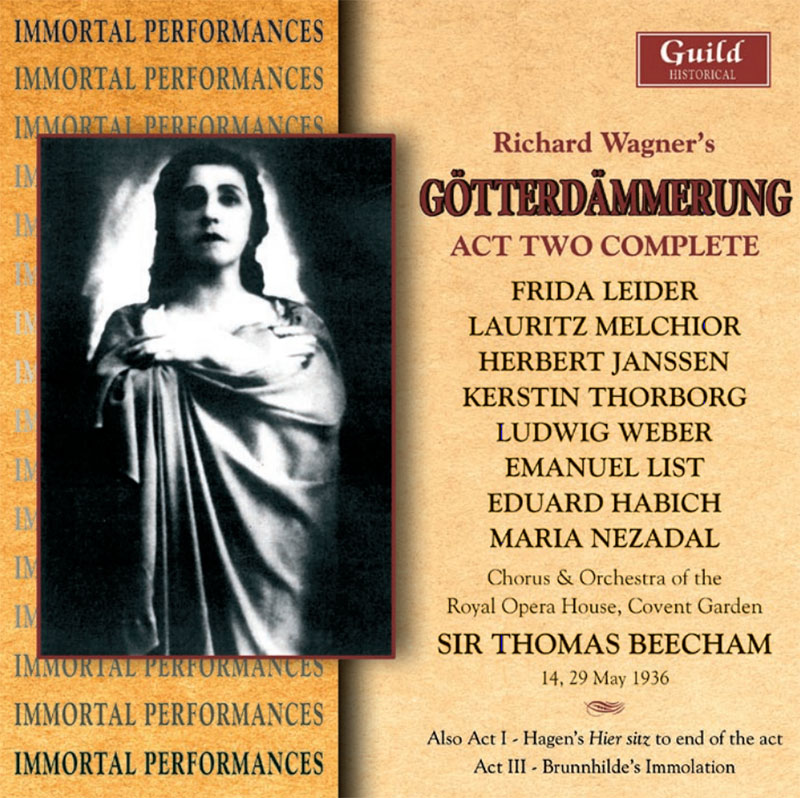

WAGNER, Lauritz Melchior, Frida Leider, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Sir Thomas Beecham

Gotterdammerung - Act Two Complete

Klassik Com Thursday December 22 05 Frida Leider (188-1975) gilt bis heute vielen als die größte Wagnersängerin aller Zeiten. Die Neuedition des erhaltenen Materials von Aufführungen der ‘Götterdämmerung’ im Mai 1936 durch Richard Caniell, die beim Schweizer Label Guild nun vorliegt, macht wieder einmal verständlich, warum das so ist. Ergänzt wurden die 2 CDs mit bekannten Berliner Studioaufnahmen der Interpretin unter Leo Blech von 1927, in denen sie mit Friedrich Schorr aus dem 3. Akt der ‘Walküre’ und mit Rudolf Laubenthal aus dem Schluß des Siegfried singt. Sowie der im Berliner Studio eingespielten Schlußszene aus der ‘Götterdämmerung’ von 1928, ebenfalls unter Leo Blech. Im Zentrum steht jedoch der fast vollständig überlieferte 2. Akt der Londoner ‘Götterdämmerung’ und ein größeres Fragment des 1. Aufzuges jener Aufführungen, das mit Hagens ‘Hier sitz ich zur Wacht’ beginnt. Aus zwei Aufführungen (vom 14. und 29. Mai 1936) setzt sich das Material zusammen, was auch zur Folge hat, dass es zwei Sänger des Hagen gibt (Ludwig Weber und Emanuel List). Will man danach noch ins heutige Bayreuth? Frieda Leiders Stimme, die sonst hauptsächlich in akustischen Aufnahmen erhalten ist, klingt in diesen elektrischen live-Aufnahmen groß und voller Wärme, ihre weit ausholende Phrasierung und ihre Reaktionen auf das Orchestergeschehen evozieren ein Rollenporträt von großer Dramatik und Eindringlichkeit. Die Stimmproduktion hat eine – nicht nur in diesem Fach – selten gehörte Leichtigkeit und führt zu vorbildlicher Textverständlichkeit. Angesichts dessen scheint es unglaublich, was für forciert singende und tremolierende Heroinen der letzten Jahrzehnte eine Karrieren als Wagnersängerinnen machen konnten. Am Pult findet sich kein geringerer als Sir Thomas Beecham. Er ist, vom dramatischen Atem der Musik angestachelt, ein wunderbar plastischer Gestalter. Mit ebenso flüssigen, wie beweglichen Tempi sorgt er für Bewegung und Drang. Den großen vokalen Momenten gibt er ausreichend Raum ohne dabei ins passive Begleiten zu verfallen. Die Streicher haben biegsame Wucht, die Bläser sind prägnant und geben die nötige Farbe. Das ist Oper als Theater verstanden, auch im Orchestergraben. Diese heute in Gesang und Orchesterbehandlung verlorene Wagner-Tradition, die durch das Dritte Reich zerstört wurde, und für einige Jahre noch an der New Yorker Met und in Buenos Aires am Teatro Colón weitergepflegt wurde, stellt so manchen heutigen auf Oberfläche bedachten Pultstar und mit seiner Partie ringenden Bayreuthsänger ins Abseits. Denn auch das Ensemble, das die Leider umgibt, ist phänomenal: Lauritz Melchior strahlender, kräftiger und klar intonierender Siegfried, Herbert Janssen Differenzierungskunst und die theatralisch ausgelotete, mit lyrischen Qualitäten und rhythmischer Präzision aufwartende Waltraute von Kerstin Thorborg. Die Klangqualität dieser seinerzeit experimentellen Aufnahmen rangiert von schwer anhörbar bis überraschend gut. Der größte Teil ist jedoch gut zu goutieren. Man hat aus verschiedenen Schelleck-Sets die jeweils besten Seiten verwendet und behutsam digitalisiert. Die Fülle des Klanges ist stets beachtlich und in den vielen gut erhaltenen Stellen auch die Klangtransparenz. Für den Hörer angenehm ist das etwas sonderbare Verfahren Überlieferungslücken durch Teile anderer Aufnahmen zu schließen. Editorisch freilich ist das, auch wenn sich die einzelnen Nachweise dazu sich im beiliegenden Booklet finden, höchst fragwürdig. Uwe Schneider Music Web December 02 I have long known about the live recording of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung from Covent Garden in 1936 conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham. Tantalising fragments from Act 2 appeared on LP during the early 1970s but this 2 CD set from Guild is the first time I have come across an attempt to assemble all the surviving recordings. What we have here is a recording of the end of Act 1 (Hagen’s monologue to close) and the entire Act 2 from Beecham’s performance; though the transfer engineers have had to patch in bits of other performances by the same singers as the final disc covering the end of Act 1 and the opening of Act 2 have not survived adequately. The Brünnhilde here is Frida Leider, one of the great Brünnhildes of the inter-war period. Guild have included Leider’s 1928 Berlin account of the Immolation scene which provides a satisfying conclusion to the Götterdämmerung excerpts. Sir Thomas Beecham is not currently best known for his Wagner conducting partly because Wagner featured less in his post-war discography. But during the inter-war years he conducted significant Wagner operas both at Covent Garden and with his own opera company. The recording of Tristan und Isolde, recorded live at Covent Garden in 1937, has existed on the fringes of the catalogue for some time though its influence is somewhat compromised by EMI’s efforts at issuing the set when they mixed up Beecham and Fritz Reiner discs and ended up producing a set which was a collage of the work of both conductors. Götterdämmerung was recorded live at Covent Garden in 1936 on two different dates with different casts, so that we hear two Hagens. Beecham’s Wagner is notable for its fleetness and flexibility, and it is good to have a record of his Götterdämmerung no matter how fragmentary. The transfer quality varies from poor to surprisingly good. These discs are never going to be ideal performances but with patience they open up a magical window onto the past. Here we can eavesdrop on a performance which took place at Covent Garden nearly seventy years ago. The cast is a fine one; besides Leider, Lauritz Melchior is an incomparable Siegfried, Emmanuel List and Ludwig Weber share Hagen and Kerstin Thorborg is a passionate Waltraute. Though Leider is associated with the role of Brünnhilde in the inter-war years, she was in fact not much older than Kirsten Flagstad, a singer with whom she has some vocal qualities in common. Leider presents a focused, flexible vocal line which only seems to lack Flagstad’s gleaming power. But at such a distant remove from the performance it is now difficult to really asses the size of Leider’s voice, at least on the basis of these records. What is undoubtedly true is that her Brünnhilde is beautifully shapely and passionate. She has a wonderful sense of line and presents Brünnhilde as shapely, womanly and feminine; still powerful and implacable but not quite the warrior maiden. It must be admitted that the orchestra does tend to dominate her voice and this is, in fact, a very orchestra-led recording. There is also a certain snatched quality to some of her high notes, but her legato is lovely. Melchior’s Siegfried is open and noble and he makes a fine pairing with Leider. He does not seem to have been in the best of voices and his upper register sounds a little effortful. But Melchior, even when not at his best, is still considerable. List and Weber are both powerful as Hagen and Herbert Janssen’s Gunther is suitably vile. Whilst Beecham’s Götterdämmerung is not really shaped into paragraphs it is undoubtedly superbly dramatic and propelled along with a wonderful impetus. The conclusion to Act 2 is glorious. The Berlin Immolation scene sees Leider projecting Brünnhilde with a slightly lighter voice but the balance with the orchestra is better than in the Covent Garden recording. This means that her top gleams properly and she rightly dominates. Guild have also included further excerpts from Die Walküre and Siegfried which Leider recorded in Berlin in 1927, enabling us to start to put together a more balance view of her Brünnhilde. These discs are the fascinating torso of a performance, recorded at a time when live recording of complete operas at Covent Garden was still in its infancy, but they remain essential listening. Robert Hugill Music Web 02.10.05 An imposing addition to the 1930s Wagnerian discography – and in better-than-hoped-for sound Firstly a note on what we have. The principal torso is the remains of Beecham’s 1936 Götterdämmerung; a chunk of Act I is extant though the first disc has been lost and equally a patch from a 1937 Melchior performance has been utilised to cover a gap after Brunnhilde’s jag’st du mich hin. Act II is not fully extant. Patches from the 1950 Furtwängler performance have been spliced into scene one and the Habich is from the 1936 Met (Bodanzky). Later there’s an example from the 14th May 1936 performance. The Immolation Scene from Act III derives from commercial discs made in Berlin under Blech in 1928. There are also excerpts from Frida Leider’s Die Walküre and Siegfried, once more with Blech but this time from 1927. Quite a complicated procedure then and one that has been accomplished with considerable care and firm supporting documentary information (a Guild speciality thankfully, otherwise hacks like me would be floundering around). The man at the helm is Beecham, a fluid, elastic but tensile Wagnerian, eloquently stressing the cantilever of the string melodies and bringing the supportive cushion of the winds to the fore. His cast is stellar and one that will be broadly known from other Covent Garden and Met performances. We hear Weber, “nasty” of tone and insinuating in Hier sitz zur Wacht as indeed we can hear Thorborg’s Waltraute. With every newly released disc Thorborg’s stature as a Wagnerian (especially – she was superb in other repertoire of course) grows. Elastic lyricism subjected to strong rhythmic control inform her exchanges with Leider in Act I Scene 3. The characterisation is powerful, the histrionic hauteur unmistakeable. For all the problems and changeable balances, scrunches and stage noises we can clearly appreciate the theatrical drama of the Leider-Thorborg scenes; Leider is regal and in consistently compelling form. Melchior’s theatrical projection allied to Olympian vocalism is as ever magnificent but so in its more inevitably circumscribed way is Janssen’s Gunther. As we’ve heard before in Guild’s Met broadcast series Janssen’s very elegance and almost refined impersonation is an acute musico-psychological perception. List is full of spittle and sawdust hectoring in his Act II Scene 4 exchanges Dir hilft kein Hirn. Note here also the stupendous Concorde-curve of Beecham’s moulding of the string lines (try from about two minutes into this scene). Problematic though this recording is the engineering time has been well spent. The bonuses are exciting enough in their own way – the Act III Immolation Scene from Berlin and the slightly earlier 1927 extracts. The catalogue numbers are given in the body of the text. Note that in the former Guild have spliced a full orchestral finale (not included in the commercial disc) so that if you possess HMV D2025-26 or any subsequent re-releases you will be in for a little surprise. The extract is so far unidentified. Period photographs of the performers grace the booklet and there are synopses, biographies and notes. An imposing addition to the 1930s Wagnerian discography – and in better-than-hoped-for sound. Jonathan Woolf