Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

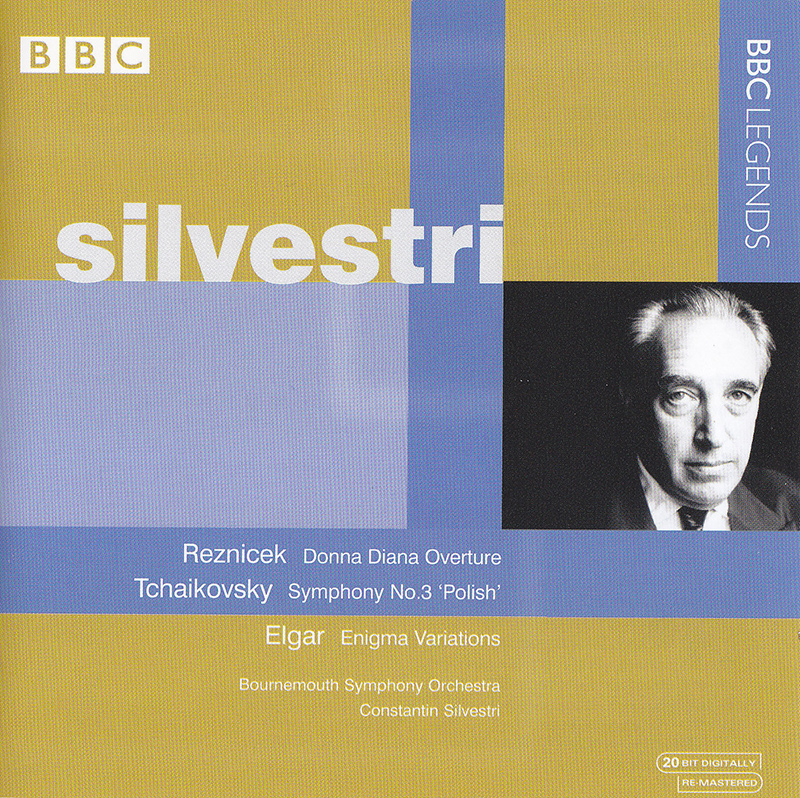

von REZNICEK, TCHAIKOVSKY, ELGAR, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Constantin Silvestri

Donna Diana Overture / Symphony No. 3 in D Major, Op. 29 'Polish' / Enigma Variations

Culled from two distinct concerts of 25 September 1962 (Reznicek) and 3 July 1967 (Tchaikovsky, Elgar), this disc exemplifies the vivacious, virtuoso work of Rumanian conductor Constantin Silvestri (1913-1969) at the height of his considerable powers. The liner notes, by clarinetist Raymond Carpenter of the Bournemouth Symphony, 1948-1987, convey their own color-commentary. It seems this concert opens with a bit of musical nepotism, as the blisteringly lovely Donna Diana Overture had been composed by Silvestri’s uncle. Ever since the classic recording of the work by Frederick Stock, I have been partial to its clever synthesis of rhythmic motion and flowing melody, the theme-song for the old “Sergeant Preston of the Yukon” television program of my youth. The “Polish” Symphony of Tchaikovsky still remains a relative rarity among his six, and even Silvestri never recorded the piece commercially. It was the Beecham 1947 recording that first revealed the potential of this most balletic of Tchaikovsky symphonies. Silvestri plays the work for its Slavic panache, often clouded by the composer’s desire to legitimize his “Germanic” leanings by treating the otherwise muscular, sinewy tunes to academic, contrapuntal procedures. Clarinet, oboe, flute, brass, and strings have their hands full in the first movement, which Silvestri sails through with assured fervor. The last pages evoke those “unbelievable cyclonic climaxes” to which commentator Carpenter refers with awed respect. The ensuing “Alla tedesca” movement in G Minor and B-flat Major limps, lilts, and swaggers, a stylized gavotte from some unnamed scene from The Sleeping Beauty. The Andante elegiaco in D Minor proves the most authentically “symphonic” movement, its scoring close to the second movement of the “Winter Dreams” First Symphony, but the woodwind and horn colors more assured. The music gravitates to an expressive B-flat Major and concludes in D Major, but not before it makes several affecting gestures in the composer’s best, romantic vein. A most unusual Scherzo follows, B Minor in 2/4 time, with constant, twittering conversation between flutes, horns, the muted strings, and Silvestri’s principal trombone. The rhythms–especially the trio-march in D Major–more than once invoke the composer’s Little Russian Symphony, the C Minor No. 2, Op. 17. An often Mendelssohnian virtuosity permeates this rendition, a streamlined performance, indeed. The last movement is a Polacca in three animated sections; and it loves to bang D Major into our heads with a decided relish, the tympani playing no small role in our indoctrination. Typically, the chorale variation of the theme must assert itself polyphonically; how else is Tchaikovsky to legitimize himself to Brahms? Silvestri manages to synthesize a dramatic, pointed performance from these disparate elements, even achieving a grand apotheosis worthy of the Bolshoi, if necessary. Silvestri always exerted tender, loving sympathy in the music of Elgar, unafraid to apply old-world musical values–like portamento and exaggerated vibrato–into scores like In the South and the Enigma Variations. The long bow rules in the violins, and the sheer expressiveness of the Elgar line becomes a natural elocution of the composer’s “nobilmente” indication. The ‘W.M.B.’ variation number 4 and the wilder ‘Troyte’ No. 6 sound effectively like Brahms–as does the martial ‘G.R.S.‘ variant at no. 11–and the first of these moves with an atavistic sway into ‘R.P.A.,’ Moderato. Nice viola and horn tone for the ‘Ysobel’ variation that features a series of concertante elements. A lithe, delicate, outdoor serenade graces the ‘W.N Variation,’ No. 8. Will no one identify the excellent viola principal of the BSO? We all await the coming of ‘Nimrod,’ which in Silvestri’s interpretation does not dawdle in sentiment, but rises with inexorable majesty to sigh for a paradise lost. The hesitant, demure figure of ‘Dorabella’ remained dear to Silvestri, who turns the episode into a dialogue for viola, oboe, and chirruping ensemble. The Andante ‘B.G.N.’ evolves a haunted waltz-cantabile whose veiled tympani and arched strings make a truly passionate moment in Elgar. So, too, the Romanza variation No. 13 belongs to itself as a quotation from Mendelssohn with strings and tympani, but also as an ominous segue to the grand finale, ‘E.D.U.’ Has the hidden theme been “Rule Britannia” or “Auld Lang Syne” or some literary motif from the Bible on our perceptions “through a “glass darkly”? Whatever the secret, Silvestri comes close to having revealed it. –Gary Lemco