Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

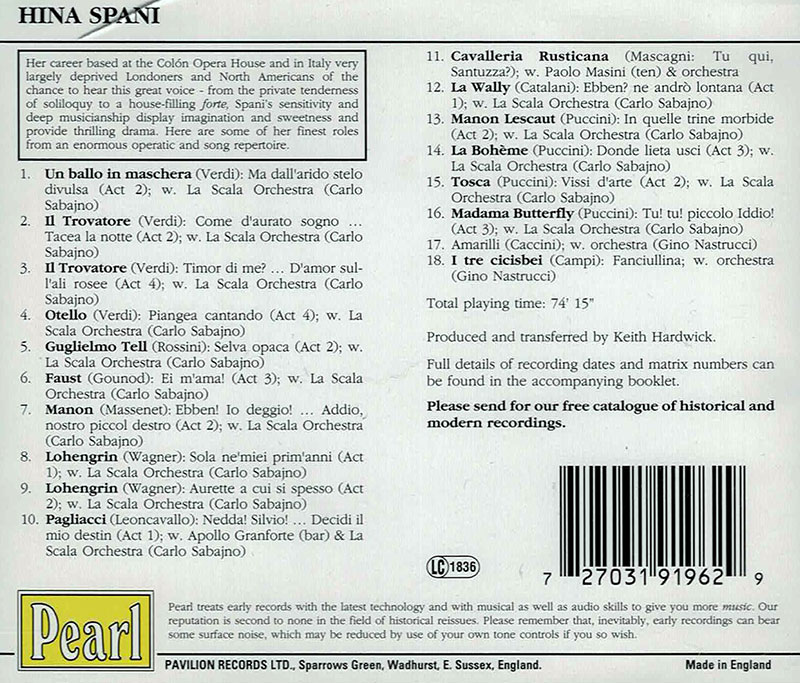

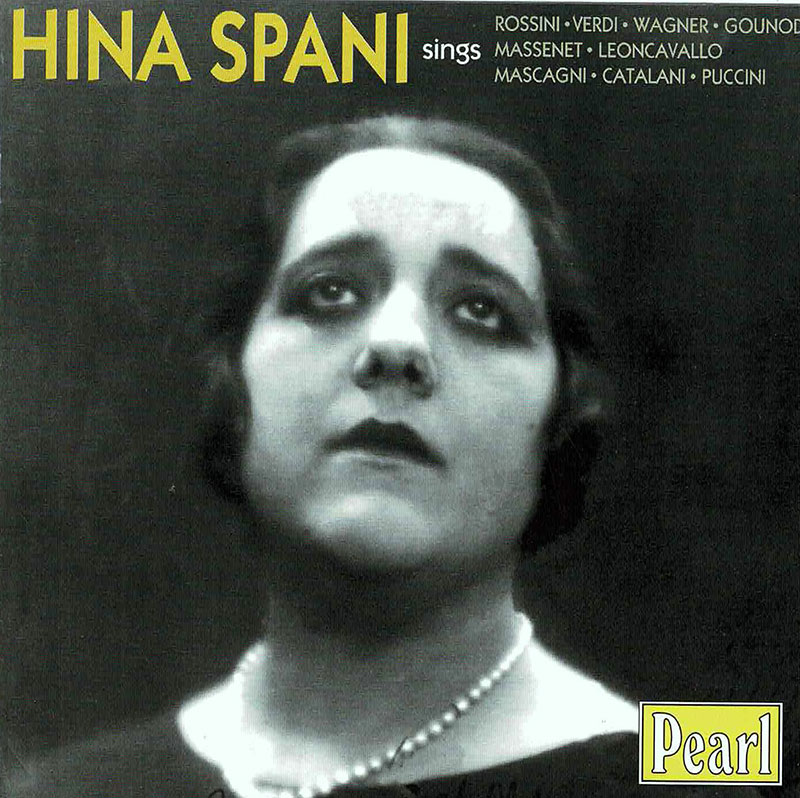

VERDI, ROSSINI, WAGNER, LEONCAVALLO, Hina Spani

Hina Spani Sings

- 1. Un Ballo In Maschera, Act 2: Ma Dall'arido Stelo Divulsa

- 2. Il Trovatore, Act 2: Come D'aurato Sogno ... Tacea La Notte

- 3. Il Trovatore, Act 4: Timor Di Me? ... D'amor Sull'ali Rosee

- 4. Otello, Act 4: Piangea Cantando

- 5. Guglielmo Tell, Act 2: Selva Opaca

- 6. Faust, Act 3: Ei M'ama!

- 7. Manon, Act 2: Ebben! Io Deggio! ... Addio, Nostro Piccol Destro

- 8. Lohengrin, Act 1: Sola Ne'miei Prim'anni

- 9. Lohengrin, Act 2: Aurette A Cui Si Spesso

- 10. Pagliacci, Act 1: Nedda! Silvio! ... Decidi Il Mio Destin

- 11. Cavalleria Rusticana: Tu Qui, Santuzza?

- 12. La Wally, Act 1: Ebben? Ne Andro Lontana

- 13. Manon Lescaut, Act 2: In Quelle Trine Morbide

- 14. La Boheme, Act 3: Donde Lieta Usci

- 15. Tosca, Act 2: Vissi D'arte

- 16. Madama Butterfly, Act 3: Tu! Tu! Piccolo Iddio!

- 17. Amarilli

- 18. I Tre Cicisbei: Fanciullina

- Hina Spani - soprano

- VERDI

- ROSSINI

- WAGNER

- LEONCAVALLO

Jeden z najpiękniejszych głosów minionego stulecia. Argentynka, wykształcona we Włoszech. Przez ponad ćwierć wieku królowała na scenach Ameryki Południowej i Europy. W Ameryce Północnej i Anglii słuchano jej jedynie z płyt. Tamtejsi melomani musieli zadowolić się jedynie entuzjastycznymi recenzjami w prasie. Dlaczego unikała Europy? Co sprawiło, że była niedoścignioną interpretatorką w europejskich operach? Kim w istoicie była dystyngowana, tajemnicza i boska Spani? HINA SPANI Hina Spani (1896-1969) was a singer on whom Britain and the United States missed out badly. She came from Argentina and trained in Milan. For twenty-five years she was a principal soprano at the Colón, Buenos Aires, and for most of that time was heard also in the leading houses of Italy. She was popular in Spain, Chile and Brazil, and in 1928 enjoyed considerable success with Melba's Opera Company in Australia. We never heard her in London, and audiences in New York, San Francisco and Chicago, so used to attracting the best talent from abroad, were similarly deprived. It is all the more surprising in that her records were available and promoted by both HMV and Victor. Moreover, she was an exceptionally versatile and useful singer, with a large operatic repertoire and unusually wide experience in concert work. Her schedule of appearances shows how opera houses regularly turned to her when new or unfamiliar works were to be performed. She was clearly a reliable musician and, as records testify, seems to have been incapable of singing without meaning and emotion. Yet something prevented that wider recognition which would have furthered her career as a recording artist and have made her name better known today. It may have been that the very Latin vibrancy of her timbre as heard on records rang less congenially in the ears of northerners. Or it is just possible that the record-buying public felt that they could not really be said to have heard her at all. Her HMV recordings were made between 1926 and 1931, which were the years when the prettiest labels were made and the coarsest shellac used. Without personal appearances to support their sales, the records lasted only a short time in the British catalogues (one only, the Boheme and Manon Lescaut coupling, remained in 1937), so that it was hard to find copies that were not rendered `difficult' by their heavy surfaces. The Italian branch, `Voce del padrone', did better, and in this present collection are two items that were unpublished in their time, which in respect of surface-noise are best of all. Modern technology, of course, can work wonders, and one can only speculate on the difference it might have made to Spani's career had it been possible to hear the voice in those original HMV issues as clearly as we hear it now. In these transfers - and indeed in the originals as played on the old machines if one listened 'through'- it is scarcely possible to miss the dramatic thrill in the voice and the sensitive imagination that guides its usage. The very first track here, the Ballo in maschera aria, is one of the finest. The tense, dark tone of the lower notes matches perfectly the midnight setting, the place of the gallows and the anxiety of heart; then with Amelia's prayer for heavenly protection the voice rises with, first, a new sweetness and then increasing fervour to the resonant full-voiced top C, all taken on a breath span that in turn matches the triple arch of Verdi's inspired phrases. It is also notable that Spani and her Milan recorders create a deeper perspective of sound than was common in those days: she exploits a full dynamic range, the sound growing to a genuinely big house-filling forte and then diminishing to the most intimate pianissimo. It is this responsiveness in detail to whatever music she is singing, and in whatever role, that makes us less likely to object that her characterisations are all very alike. Perhaps in other parts of Madama Butterfly, rather than in the powerful soaring phrases of the finale (track 16), she would have characterised with a more childlike voice; perhaps other passages in Faust would have revealed a more maidenly Marguerite than the rapturous abandonment at the conclusion to the Garden scene (track 6). The great thing is that each character in turn lives a real life - Elsa, for example, is both a girl of dreams and of heroic vision (tracks 8 and 9), Manon sings the sentimental farewell to the little table in her Parisian love-nest with all the private tenderness of soliloquy. That these were all roles she sang on stage no doubt helped. Amelia in Ballo was one of her earliest lyric-dramatic parts, added to the repertoire in 1924; the Trovatore Leonora followed in 1928, the year of her lovely recording of the aria from Act 4. She sang Mathilde in Guglielmo Tell first at the Colón in 1922 with the Irishman John O'Sullivan as her Arnoldo. Faust was one of the operas taken on tour in Australia; La Wally was among her successes at La Scala; Pagliacci she sang often, most memorably in a performance at Buenos Aires in 1915 with Caruso and Ruffo. Butterfly was among the roles she undertook in her final seasons of 1939 and 1940; the rest were scattered widely over a career which is said to have embraced some seventy roles, ranging from Aida, Turandot and Lady Macbeth to parts in operas by Carissimi, Rameau and Monteverdi. Her song repertoire was reputedly even more extensive. Even at the height of her operatic career she would devote a sizeable part of the year to concert work, and on retirement from the stage continued to give recitals till 1946. On records she sang only in Spanish and Italian and, as with the operas, the few pieces that remain to represent her now are no more than random samples of a wide-ranging art. The two included here are charming examples. `Amarilli' by Giulio Caccini (c. 15451618) assures the lovely Amaryllis that inspection of the lover's heart would reveal her name inscribed there: not a very original thought, perhaps, but a richly expressive melody and a coda which Spani sings with delicious softness and fluency. Less wellknown is the pretty Tanciullina' attributed to Vincenzo Ciampi (1719-1762) from Gli tre cicisbei ridicoli, a composite work, with `Tre giorni son the Nina' as its principal surviving number. A humorous piece, with its refrain of "Flow, flou, mariez-vous, belle", Tanciullina' tells of love's misfortunes and for a remedy recommends wedlock. The reflection that it is no use sighing over the small output - of recordings by this distinguished singer is unlikely to stifle the sigh. Tantalisingly listed among recordings made but unissued are the jewel song from Faust, Butterfly's entrance, Micaela's aria, and (unbearable to contemplate) `Addio del passato'. Of the other recordings extant most are of songs and are hardly numerous enough to fill a second disc. There is also a recording of the Love duet from Otello, which can be found in the second volume of Pearl's Giovanni Zenatello Edition (GEMM CDS 9074). Of the other singers with whom Spani recorded, the tenor Paolo Masini is not to be confused with Galliano of that name, nor on this showing (and I know no other) is he very likely to be. Apollo Granforte (1886-1975) was of course one of the leading Italian recording baritones of the interwar years and his part in the Pagliacci duet shows him in excellent form. Spani herself died at Buenos Aires in 1969, aged 73. She lived an active life after retirement, as an enthusiastic teacher at the Conservatoire. When the late Desmond Shawe-Taylor visited her in 1958 she was still ready to sing - Beethoven's Wonne der Wehmut', to her own accompaniment. "To her legion of distant admirers (wrote Shawe-Taylor) Mme. Spani was anxious to send ... her affectionate good wishes" (Gramophone, July 1958). Let us hope that the admirers are still legion, and that this new disc may help to swell their ranks. JOHN STEANE Producer's Note: Hina Spain made some of the most exciting and satisfying operatic records to be heard from the early years of electrical recording. The pity is that there were so few - and that reasons, no doubt, of economy prevented us from having any of her operatic roles in their entirety. We might have had Otello with her, Zenatello and Granforte, instead of the worthy but humdrum version with Carbone and Fusati (how much more culpable, however, was Victor/RCA-Victor in ignoring the fabulous possibilities of New York's Metropolitan Opera casts during the 'thirties - not to speak of Messrs. Toscanini, Reiner, Bodansky and Leinsdorf. Some amends were made in the nineteen forties and 'fifties, but by then it was almost too late). To return to Spani. During the period 19291931 there are no less than 26 letters in the EMI Archives between The Gramophone's Head Office, the Milan Headquarters of HMV, Carlo Sabajno and Madame Spani herself. Between them they reveal the Company's increasing reluctance to persevere with what it regarded as her refusal [o compromise with the limitations of the current recording techniques. A letter to Sabajno dated 9th May 1929 highlights the problem: "Unfortunately, the records are a shade 'over recorded', and although the voice is only a trifle too loud it produces, when combined with the Orchestra, several unpleasant 'chattering notes' which render the records impossible to issue ..." And six days later, writing to Spain about the same records Head Office said: "... we find that the voice is somewhat heavy, and the 'Cello is too prominent. As these are Chamber songs, they should not be so voluminous. For her part, Spani was for ever trying to persuade the Company to let her make more records (a series of 6 Tosti songs nearly, but not quite, came to pass). She also complained, not unreasonably, that her records were inadequately publicised in Spain and Argentina. And her efforts to persuade HMV to intervene with the Covent Garden management met with a fairly dusty response: Regarding Covent Garden and Colonel Blois, your name has been placed before the Management on many occasions, and they are well aware of your ability and standing. No doubt the reason they have not given you an invitation is that all the roles have been filled for the season." So much the worse for the Company and Covent Garden! Warmest thanks to the EMI Archive for generously making the Spani file available to us, and to Richard Bebb for the loan of most of the records used. KEITH HARDWICK