Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

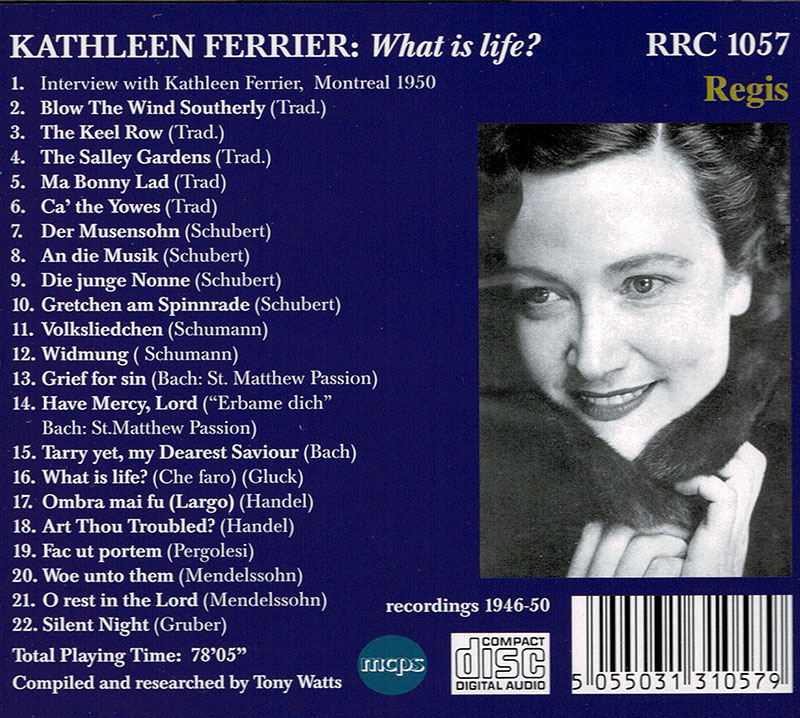

TRADITIONAL, SCHUBERT, SCHUMANN, BACH, HANDEL, Kathleen Ferrier

What is Life

- Kathleen Ferrier - contralto

- TRADITIONAL

- SCHUBERT

- SCHUMANN

- BACH

- HANDEL

Kathleen Ferrier "What is life?" (Favourites) Following the death of Kathleen Ferrier of cancer at the age of forty-one in 1953, much of the musical world was in a state of shock. It had been known that she had been desperately ill but rumours had circulated to the effect that she was making a recovery and there were plans for her appearance in several continents: she would be touring Africa and America; she would sing in a new work by Stravinsky; there would be more recordings, most notably of Britten's music; and she might be singing Wagner (a composer she was known to dislike) at Bayreuth. Earlier that year one of her greatest ambitions - to sing in a production of Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice conducted by her beloved Sir John Barbirolli at Covent Garden - had been realised. However the project had to be abandoned after the second performance when Ferrier had felt chronic stabbing pains in one leg leaving her scarcely able to move. Many people in the audience did not notice her discomfort for she was not given to wild histrionics on stage: many years before she had taken the advice to act with her voice, and that is how she continued the performance. But those closest to her knew that it would be just a matter of time before she would succumb completely to the cancer that had already gripped her. Even now, almost fifty years after her death there are many who cannot listen dry eyed to her recordings: some pieces, such as Mahler's DerAbschied (Farewell) from his great songsymphony DasLiedvon derErde (Song of the earth) and Chefaro senza Euridice (What is life without thee?) from Gluck's Orfeo have a poignancy of their own even without their relevance to Kathleen Ferrier's own tragically short life. As sung by her they are unbearably moving; they are also mementos of one of Britain's most glorious voices. Kathleen Ferrier was born in Higher Walton, Lancashire on 22 April 1912, the youngest of three children. Her parents were both teachers who enjoyed music. When young she began piano lessons and showed a tremendous talent at this instrument, later winning prizes at several important competitions. However Kathleen's parents faced a stark choice when she was fourteen, for her elder brother had emigrated to Canada, but was showing signs of getting into trouble. If indeed he were deported back to Britain Kathleen's parents would have to find his fare home and in order to provide for this her parents removed Kathleen from school. To earn money she worked in the local telephone exchange and in order to maintain her interest in music she accompanied a singing group, occasionally joining in herself. Friends were impressed by her voice and in 1931 she started taking singing lessons. When Kathleen married in 1935 she had to give up her job at the telephone exchange, but the marriage did not work and she and her husband soon separated. Gradually she began to get singing engagements and learned the contralto solos from TheMessiah, Elijah and a few songs such as Vaughan Williams' Silent Noon. Sadly her mother did not live to see her daughter become famous, for she died just prior to her daughter's first broadcast in 1939. Kathleen's next teacher broadened her range so that she could encompass two octaves from G below middle C to high G. He also taught her a large part of the Baroque repertoire as well as the part of the Angel in Elgar's Dream of Gerontius. During the War she sang for CEMA (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts) who toured troop camps. In 1942 she was signed up by Ibbs and Tillett who arranged a busy schedule for her, singing numerous Messiahs and Elijahs alongside the likes of Isobel Baillie, Joan Cross, Peter Pears and Roy Henderson, from whom she began to take lessons, having moved to London. Henderson took enormous care with her voice, saying later that he realised he would have to be wary so as not to tamper with its unique timbre. He was amazed by the size of her throat cavity commenting that one could have shot a fair-sized apple down it. Henderson held strong views as to what she should or should not be singing: he vetoed certain works such as the Verdi Requiem and only allowed her to take on the more demanding works very gradually. Throughout her career she worried that her repertoire was too small and was always trying to extend it. However she never showed the slightest interest in learning opera (apart from a few select roles) as she was conscious of her limited acting resources. Ferrier was often a bundle of nerves on stage (less so on the concert platform) and those outside her immediate circle of friends were amazed when first confronted by her ribald sense of humour. Most of the time she was refreshingly down to earth, but could also play (with some justification) the grande dame: for example she felt badly let down by her concert promoters in America and listed numerous examples of how badly she was being treated compared to other artists. On her following trip she found the red carpet laid out for her and scarcely a hiccup occurred. More to the point she went home in funds, for previously she had overpaid on taxes, advertising costs and she discovered too late that her accompanist was suffering from a nervous breakdown! She suffered anxieties over her acting and was mortified when her conductor on several occasions (Fritz Stiedry) made fun of her in front of the cast and stage technicians. In the wings however she would reduce those same singers and stage hands to helpless giggles by her suggestive behavior with her costume. She asked for a special prop (in this instance, since the production was Orfeo, the prop was a lyre) to be made so that if Stiedry persisted in humiliating her, she could beat him over the head with it! Despite her awful experiences with Stiedry and her wayward accompanist she enjoyed a productive relationship with many accompanists and conductors. She encountered Gerald Moore early in her career when he played for her in four test pressings for Columbia in 1944 and although she subsequently worked in the main for Decca, they remained firm friends and colleagues. Her usual accompanists were Phyllis Spurr and the Canadian John Newmark (who stepped in to save the afore-mentioned American tour) and late in her career she appeared in Lieder recitals with Bruno Walter, whose piano playing however attracted divided comment. Many of her finest performances were with Sir John Barbirolli, to whom she was especially close. He was particularly keen to enlarge her repertoire so that she did not `degenerate into that queer and almost bovine monstrosity so beloved of our grandfathers... the `oratorio contralto". He taught her, for instance Chausson's lovely Poeme de Amour et de la Mer. Whilst agreeing to learn this piece she instructed her agent Emmie Tillett to tell Sir John to play loudly so as to cover her Lancashire accent. Sadly the two were signed up to different record companies and so little can now be heard of their work together. She made a number of fine recordings with Sir Malcolm Sargent, including the best selling What is life without thee and both well-known and less familiar arias by Handel; whilst with her beloved Bruno Walter she made the famous Mahler records. Other much admired conductors with whom she collaborated include Ernest Ansermet and Eduard van Beinum (with whom she performed the premieres of Britten's Rape of Lucretia and his Spring Symphony respectively), George Szell, Otto Klemperer Josef Krips, Pierre Monteux and Boyd Neel. She was much loved by fellow singers, who sensing her insecurity at times, would be unstinting with help and advice. Much of Ferrier's repertoire was recorded by Decca, although she was initially under contract to Columbia; these records include numerous Lieder and folk songs, arias from sacred works and the few operas in which she sang, and longer works by Mahler and Brahms. After her death other recordings, largely taken from the many broadcasts she made, appeared and in some ways they are the most interesting, for they demonstrate the fact that her repertoire was in fact rather more extensive than was generally believed. Far from restricting herself, she sang much modern material by composers such as Rubbra and Berkeley as well as the better known examples by Britten. At the height of her career she was one of the busiest artists on the international circuit with regular lengthy tours to America, Scandinavia and Holland (where she was a particular favourite). She was the firstBritish singer to appear at the Salzburg Festival and she also gave memorable performances at La Scala Milan (in Mass in B minor) and Vienna. She was a regular visitor to the Edinburgh Festival and the Proms, and sang in many and varied venues throughout Britain: even when `Klever Kaff (the nickname she gave herself) was most in demand, she would always insist that time be kept aside so that she could give concerts in the North of England. © 2001 James Murray