Logowanie

ABSOLUTNIE OSTATNIE!!!!!

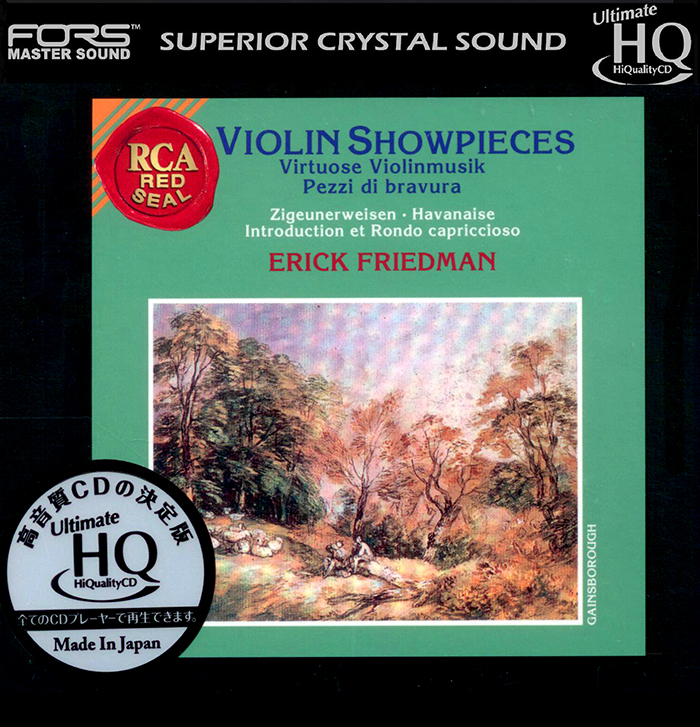

SARASATE, WIENIAWSKI, RAVEL, Erik Friedman, Walter Hendl, Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Violin Showpieces

Ultimate HiQuality CD

Top Music Ensemble

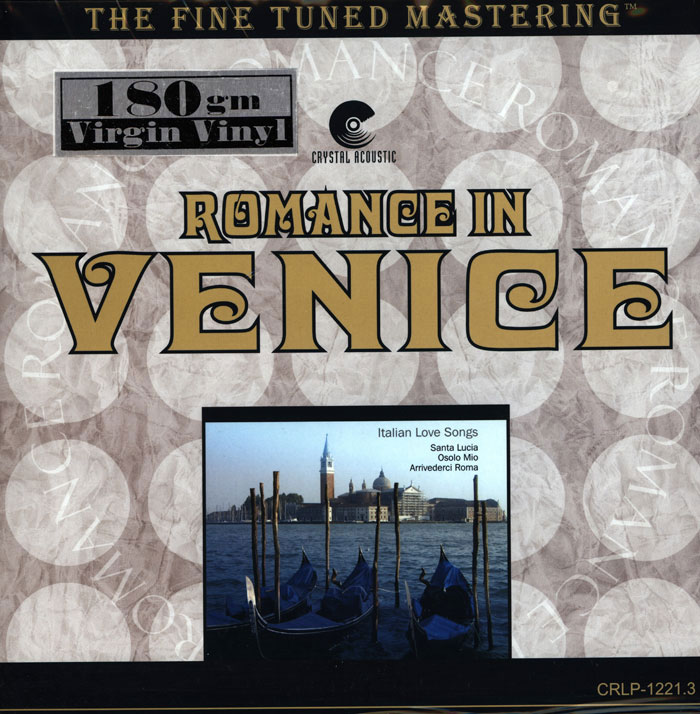

Romance in Venice

The Fine Tuned Mastering - wyrafinowana wersja SACD HYBR 32bit/192kHz

Antonio M. Xavier & Denver Music Orchestra

Lover's Romance - vol.1

Special Limited Edition! NUMEROWANA!

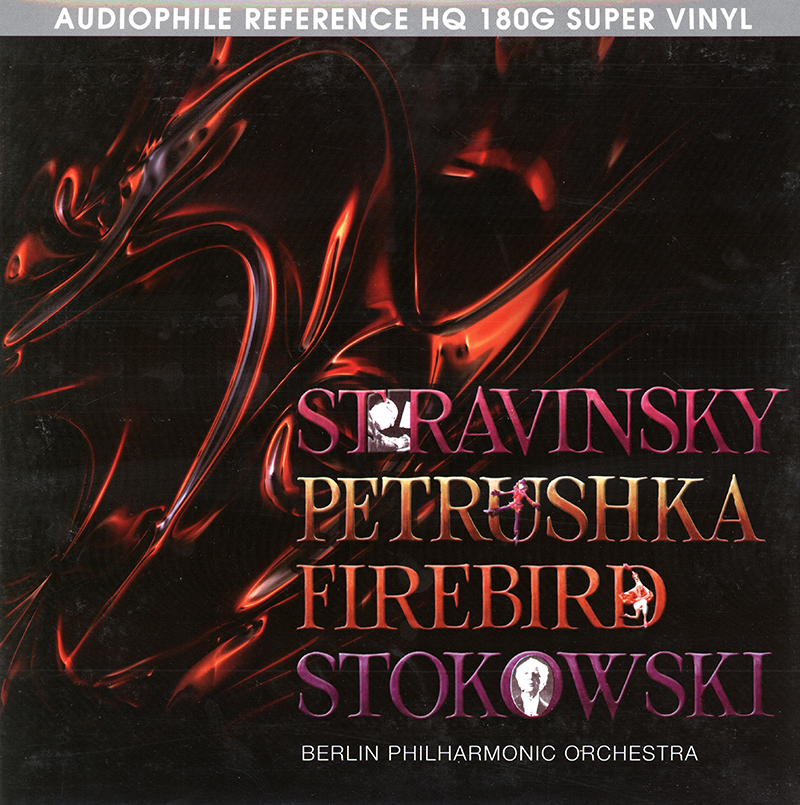

STRAVINSKY, Berlin Philharmonic, Leopold Stokowski

Petrushka / Firebird

SUPER VINYL - EDYCJA NUMEROWANA - TYLKO 500 SZTUK

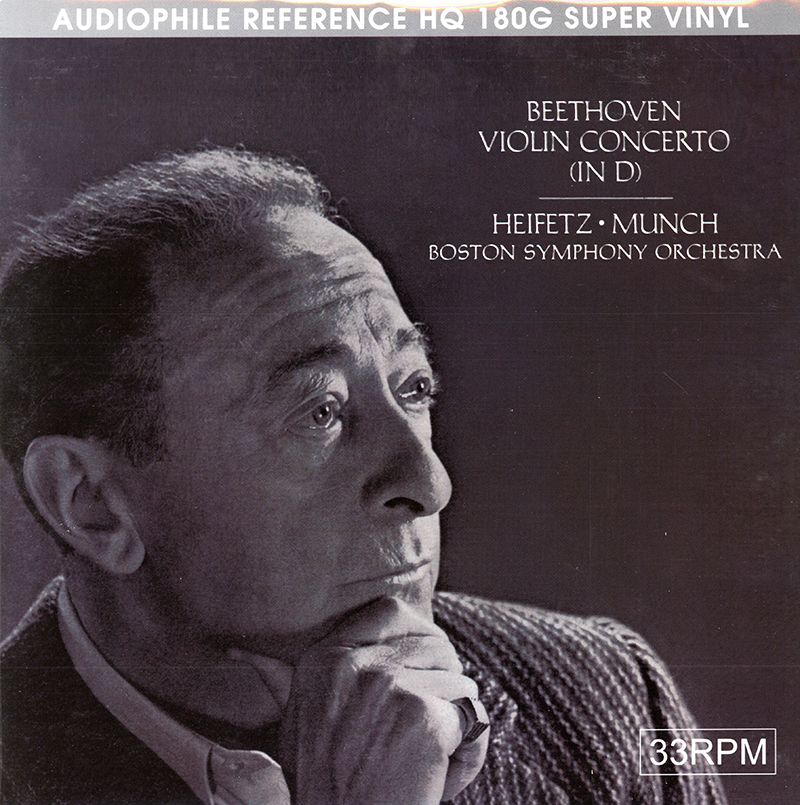

BEETHOVEN, Jascha Heifetz, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Charles Munch

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

edycja numerowana - 500 egzemplarzy w skali światowej - SUPER VINYL

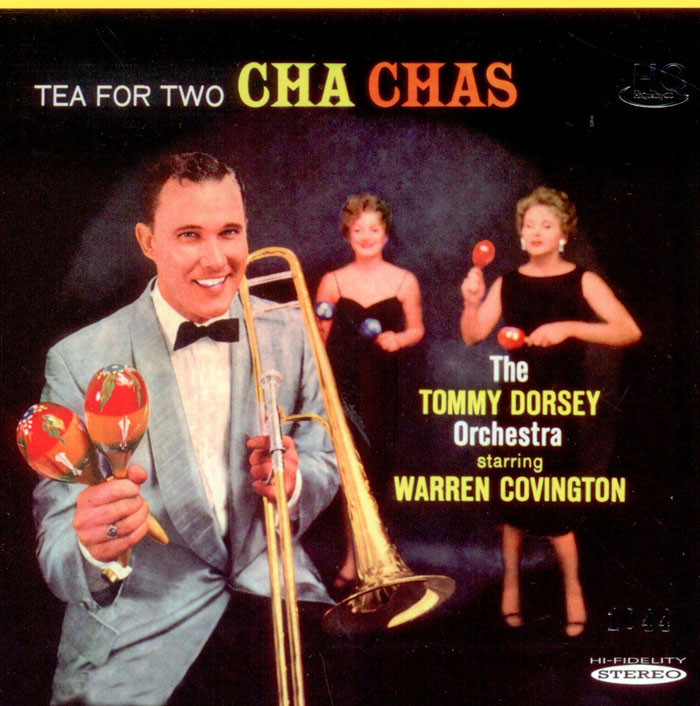

The Tommy Dorsey Orchestra

Tea For Two Cha Chas

The Tommy Dorsey Orchestra Starring Warren Covington

SpeakersCorner - OSTATNIE!!!!

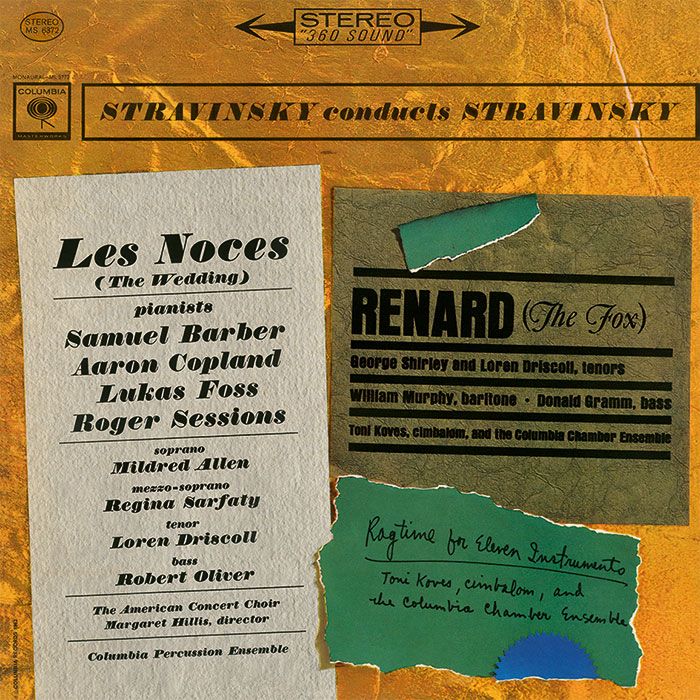

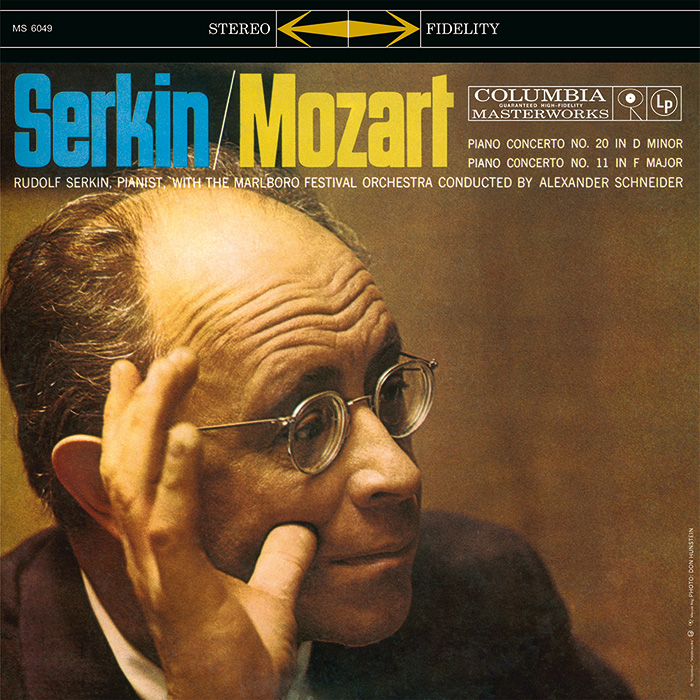

MOZART, Rudolf Serkin, Alexander Schneider, Marlboro Festival Orchestra

Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor / Piano Concerto No. 11 in F Major

Columbia Masterworks

To LATO!

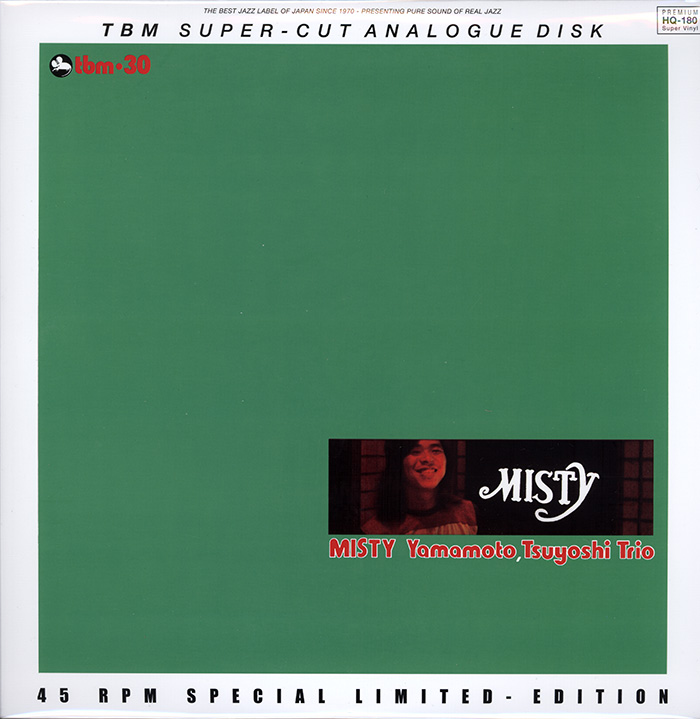

Tsuyoshi Yamamoto Trio

Misty

DO TEJ PORY NIKT, NIGDZIE NIE NAGRAŁ I NIE WYPRODUKOWAŁ LEPSZYCH PŁYT WINYLOWYCH!

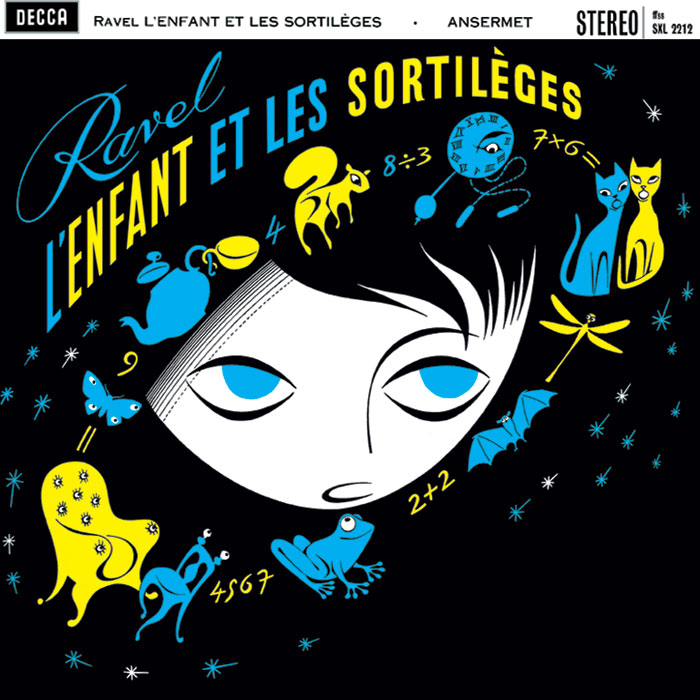

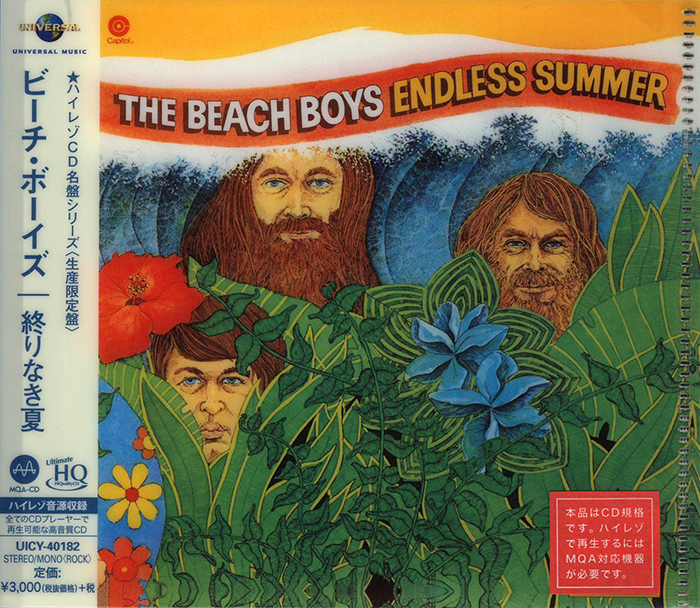

Modern Jazz Quartet

Third Stream Music

PANIE I PANOWIE - PIERWSZY RAZ NA CD!!

>>> Większa okładka A <<<

Pianist John Lewis, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, bassist Ray Brown and drummer Kenny Clarke first came together as the rhythm section of the 1946 Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra and they had occasional features that gave the overworked brass players a well-deserved rest. They next came together in 1951, recording as the Milt Jackson Quartet. In 1952 with Percy Heath taking Brown's place, the Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ) became a permanent group. Other than Connie Kay succeeding Clarke in 1955, the band's personnel was set. In the early days Jackson and Lewis both were equally responsible for the group's musical direction but the pianist eventually took over as musical director. The MJQ has long displayed John Lewis's musical vision, making jazz seem respectable by occasionally interacting with classical ensembles and playing concerts at prestigious venues, but always leaving plenty of space for bluesy and swinging improvising. Their repertoire, in addition to including veteran bop and swing pieces, introduced such originals as Lewis' "Django" and Jackson's "Bags' Groove." The group recorded for Prestige (1952-55), Atlantic (1956-74), Verve (1957), United Artists (1959) and Apple (1967-69) and, in addition to the many quartet outings, they welcomed such guests as Jimmy ...

This Atlantic LP has some unusual performances by The Modern Jazz Quartet. Two selections ("Da Capo" and "Fine") combine The MJQ (which is comprised of vibraphonist Milt Jackson, pianist John Lewis, bassist Percy Heath and drummer Connie Kay) with the Jimmy Giuffre Three (Giuffre on clarinet and tenor, guitarist Jim Hall and bassist Ralph Pena), on "Exposure" six chamber classical musicians add color, and a pair of other numbers ("Conversation" and the very successful "Sketch") match The MJQ with the Beaux Arts String Quartet. There is plenty of thought-provoking music on this out-of-print album even if the idea of creating a "Third Stream" between jazz and classical music never came to pass. — Scott Yanow

During the last year, Gunther Schuller, a composer and French horn player favorably known in both the jazz and longhair words, has been heralding the arrival of what he calls "a third stream" of music - a music that is neither jazz nor classical, but that draws upon the techniques of both. As examples, he has cited works of George Russell, John Lewis, Bill Russo, John

Benson Brooks and himself.

John S. Wilson

The New York Times (May 17, 1960)

One of the most rewarding experiences jazz has had to offer during recent years has been that of watching the development of The Modern Jazz Quartet. Coming together early in the Fifties, it was at first little more than a frame for Milt Jackson's improvisations on standard jazz pieces and ballads. Gradually, however, owing to john Lewis's singular powers as composer and arranger and, no less, to the remarkable adaptability and resourcefulness of the other members of the group, it has assumed a unique place in contemporary jazz, and, indeed, in jazz history.

There are significant parallels between the Quartet and the Duke Ellington orchestra. The MJQ is dominated by the personality and compositional bent of Lewis, just as the Ellington orchestra always has been by its leader. Yet Lewis's pieces, like Ellington's. are never written in abstract, but, on the contrary, with the especial musical capabilities, and needs, of each member of the group decisively in mind. There is, of course, the maximum latitude for improvisation and creative interpretation, so the relationship between composer and performers is essentially a reciprocal one which usually results in music that is largely created by the performers, yet finally shaped by the composer.

Thus it has an immediacy of expression that is only to be found in improvisation, together with the formal balance which only a composer can impart. In reconciling the rival claims of composition and improvisation so convincingly, Lewis has brought off one of the most difficult achievements in jazz, and placed the Quartet's work within the same tradition as that of the few other outstanding jazz composers: Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk. The freedom and adaptability of The Modern Jazz Quartet is by now such that, besides creating a body of music as individual as any in jazz, they are able to combine with other groups without losing any of their distinctive qualities. It is this aspect of their achievement that is illustrated on this LP.

The first two items combine the resources of the MJQ and Jimmy Giuffre's trio, and make subtle use of the contrasting tone-colors of vibraharp, clarinet, guitar and piano, and of the heavier sound of the ensemble with its two double basses. Da Capo is based on the alternating development of two contrasted ideas. After the introduction, we hear first a gay, dancing little figure on the vibraharp and this is succeeded by a brief pastoral melody on the clarinet.

Da Capo uses vibraharp and clarinet as its chief protagonists; in contrast, Fine, which is a rondo, employs the instruments most of the time in contrasting pairs. Its subject is a single jaunty phrase announced at the outset by the piano. This is at once freely varied by the clarinet, vibraharp, guitar, bass and percussion in turn.

These two pieces were recorded one right after the other; the seven men played straight through, and no one thought a second take was necessary. The group's work has a spontaneity that is entirely in keeping with the kind of formal cohesion and relationship of part to whole that the members of the MJQ so often achieve.

Exposure, John Lewis's music to the United Nations documentary film of the same name, is played by a small chamber ensemble built around the MJQ. The themes, and, indeed, the whole melodic development, have that quality of seeming conventional simplicity, while really being unusually fresh and eloquent, that at once marks them as the work of John Lewis. The clarity of the instrumental textures, the subtly changing tone-colors and the skilful interweaving of the parts are also unmistakably his.

Likely to be more controversial are the two pieces with The Beaux Arts String Quartet. Lewis's Sketch is a brief attempt to employ strings in a jazz composition. The sheer loveliness of the sound produced by the combination of vibraharp and piano with string should give pause to anyone who has made up his mind that strings, cannot, or should not, be used in jazz. Clearly, Lewis's problem here was to allow for the fact that the string players phrase and accent differently

than the jazzmen and, while writing music suitable to each group, maintain over-all unity. Within the modest dimensions of this composition, he is entirely successful, and Sketch is a delightful piece to listen to.

In Gunther Schuller's Conversation, the strings dominate the first part of the piece, with the other instruments making coloristic, harmonic and percussive additions. Tension is built up, mainly by the strings, and the two groups gradually assume equal partnership in what becomes

an extremely imaginative fragmented texture. (The way in which tension is increased reminds one of Bartok's quartets, but the pointillist manner of handling the instruments in this section shows the influence of Webern.) Tension is released by the entry of the MJQ as such, who go on to a typical collective improvisation. The strings re-enter and begin to reintroduce the tension. An interplay between the relaxation of one group and the tension of the other is produced, and is finally resolved in the sudden ending.

Like Lewis, Schuller recognized the different requirements and emotional connotations of the two groups and built his music on the differences. Neither of these works endeavors to mix classical and jazz devices together in the kind of artificial fusion aimed at by the "symphonic jazz" composers. Rather they successful attempts to create music in which the two idioms remain distinct, but complement each other in a way that heightens the qualities of each. We can only wait with impatience to see what more can be done in this direction.

MAX HARRISON

Contributor, The Jazz Review