Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

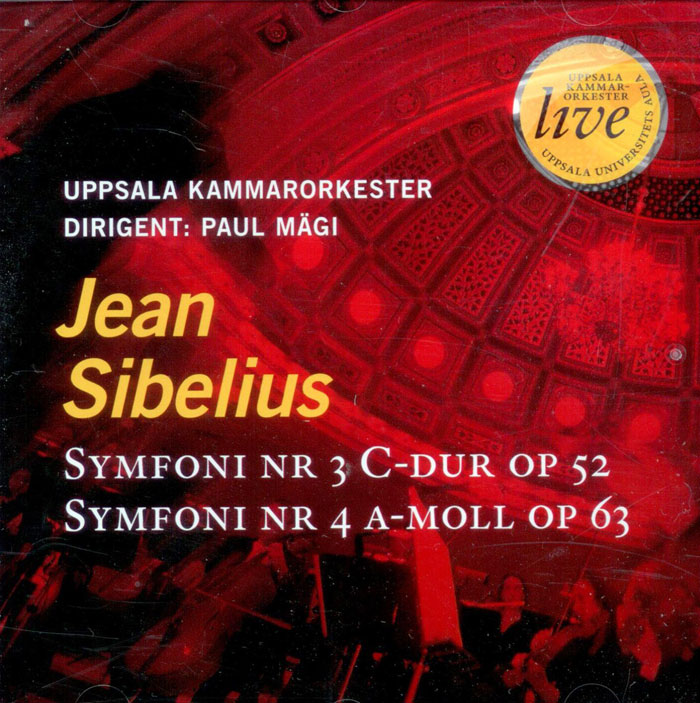

SIBELIUS, Uppsala Chamber Orchestra, Paul Magi

Symphony No. 3 and 4

- Uppsala Chamber Orchestra - orchestra

- Paul Magi - conductor

- SIBELIUS

nagranie o szczególnych walorach brzmieniowych

In his third Symphony, Sibelius partly returned to the classical ideal of style, with its reserved temperament and general chamber-music characteristics. With the exception of the four horns and three trombones, it is the classical Viennese orchestra he makes use of, allowing the strings to dominate and constraining the power of the brass to just a few instances. Everything is highly concentrated and prudently balanced. A tension between major and minor is noticeable throughout the symphony and is traceable to a short whole-tone scale with an appurtenant triton interval that recurs in various guises. The first movement has a propelling pulse and a clear sense of direction. The second movement, with its pastoral and meditative mood, is uncomplicated music, while the third movement must be counted among the boldest Sibelius had achieved to that point. It has the character of both scherzo and nale, and Sibelius himself describes it as "the crystallization of thought out of chaos." It is a struggle between several motif cells, harmonies, and rhythms that unstoppably lead forward to the nale theme and the outpouring that concludes the symphony. It was premiered in 1907 before a largely puzzled audience. Ever since it has been relegated to an undeservedly obscure place among Sibelius's symphonies. Sibelius's Symphony No. 4 was started in 1909 and premiered in 1911. He pointed out to Gustav Mahler regarding the essence of the symphony "that I admired its stringency and style and the deep logic that created an inner connection between all the motifs," and it is fascinating to see just how well this characterizes the music. Everything found in the third symphony is also in evidence here - the whole-tone scale with its triton interval, harmonic elds of tension. But the structure is so much more radical, bolder, and Sibelius has pared away everything super? uous - no arti cial gimmicks, no eruptions of sound. All movements die off in pianissimo. Nevertheless it is not pessimistic music, even though there were no kudos from either the public or the critics after its premier. Sibelius expressed much later that he was very happy with the work and that "I still cannot find a single note that I could have omitted, nor is there anything I could have added, which to me is a source of strength and contentment. The fourth symphony represents a very essential and large part of me."