Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

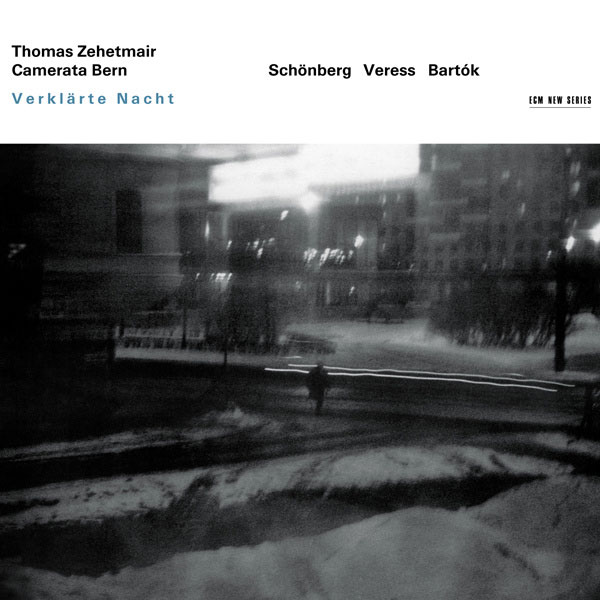

SCHONBERG, VERESS, BARTOK, Thomas Zehetmair, Camerata Bern

Verklarte Nacht / Transylvanian Dances / Divertimento for string orchestra

Thomas Zehetmair - Verklärte Nacht

01. Verklärte Nacht, for string orchestra (arr. from String Sextet, Op.4) (26:44)

02. Transylvanian Dances (4) for string orchestra- Lassu (3:35)

03. Transylvanian Dances (4) for string orchestra- Ugrós (2:43)

04. Transylvanian Dances (4) for string orchestra- Lejtos (4:57)

05. Transylvanian Dances (4) for string orchestra- Dobbantós (2:20)

06. Divertimento for string orchestra, Sz. 113, BB 118- I. Allegro non troppo (8:42)

07. Divertimento for string orchestra, Sz. 113, BB 118- II. Molto adagio (8:54)

08. Divertimento for string orchestra, Sz. 113, BB 118- III. Allegro assai (6:53)

- Thomas Zehetmair - violin and conductor

- Camerata Bern - orchestra

- SCHONBERG

- VERESS

- BARTOK

Splendour falls on everything around,

you are voyaging with me on a cold sea,

but there is the glow of an inner warmth

from you in me, from me in you.

–Richard Dehmel, “Transfigured Night” (trans. Mary Whittall)

It’s difficult to believe that the first performance of Arnold Schönberg’s Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night) in 1901 incited a riot, prompting one critic to report, “It sounds as if someone had smudged the score of Tristan while it was still wet.” Structured as it is around the eponymous poem by Richard Dehmel, in which two lovers test their resolve while wandering in moonlight, the gossamer threads of night are its makeup. Along with The Book of the Hanging Gardens, it is one of the composer’s most visceral works. Not easy listening, to be sure, but nothing worth coming to blows over, either. Its lyrical chromaticism is lush yet opaque and descriptive to the core. Its contours slowly come into focus like a whale from a dark sea, Zehetmair’s violin waiting along with the seagulls for any morsels to escape from its yawning food trap. The Camerata Bern pays strictest attention to rhythm, caressing the physiognomy of every beat with its strings. Though branded as a nocturnal affair, the piece also resounds with light. Certain sections sound like a magnified string quartet, while others breathe with the lung capacity of a full orchestra, but always with characteristic insulation. Like Wagner at his most self-effacing, Schönberg emotes with high narrative volume, as though a ballet and an opera had been stripped of words and collapsed into this one glorious whole.

After a glassy stillness that leaves us transfigured ourselves, the Four Transylvanian Dances of Sándor Veress pull us to our marionetted feet with spirited urgency. The second of these, with its finely wrought pizzicato beads, is notably heartwarming, while the fourth contrasts processional ceremony with outright exuberance. I can hardly imagine a better segue into Béla Bartók’s famed Divertimento (1939), of which the opening is perhaps the Hungarian’s most recognizable motif. Lower strings emerge as a major consonant force against the more adventurous uppers, which dance their way into the Adagio with infectious verve. The musicians’ dynamic control is on full alert here, as quiet restraint carries over into a cyclical swell of emotive power. The third and final movement is played to perfection. Its accentuating fingerboard slaps, solo cello, and open-stringed double stops stand out with scintillating clarity, all wrung through an imitative filter before ending with a pizzicato-friendly “micro-ballet.” The Divertimento, a more precise rendering of which I cannot recall, was the result of a commission by patron Paul Sacher, whose importance one can gauge further in ECM’s kaleidoscopic tribute album.

Verklärte Nacht scores another hit for Zehetmair, whose quartet album pairing Hartmann and Bartók made a concurrent appearance to equal acclaim. There’s no reason why you shouldn’t have both on your shelf.