Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

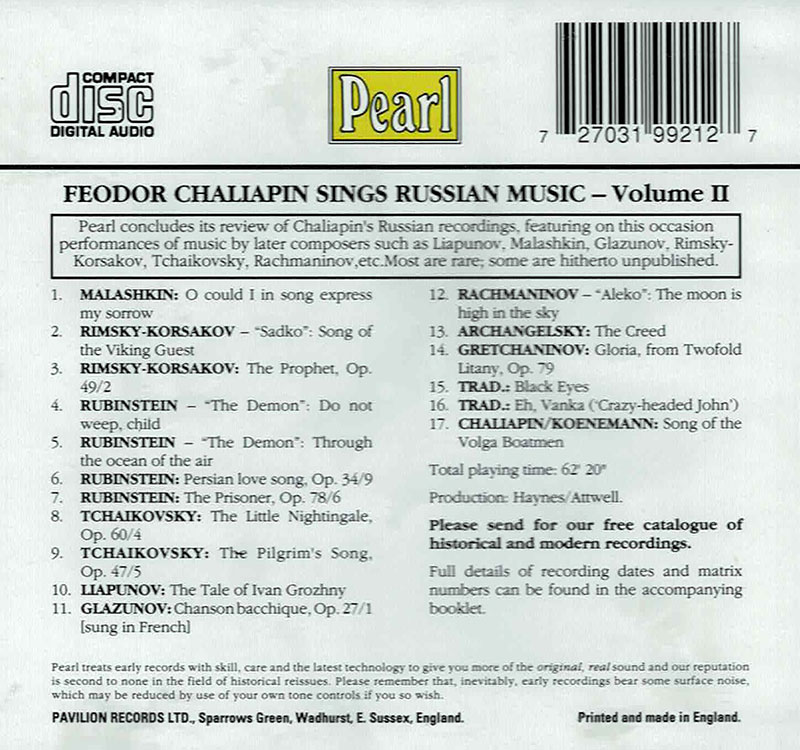

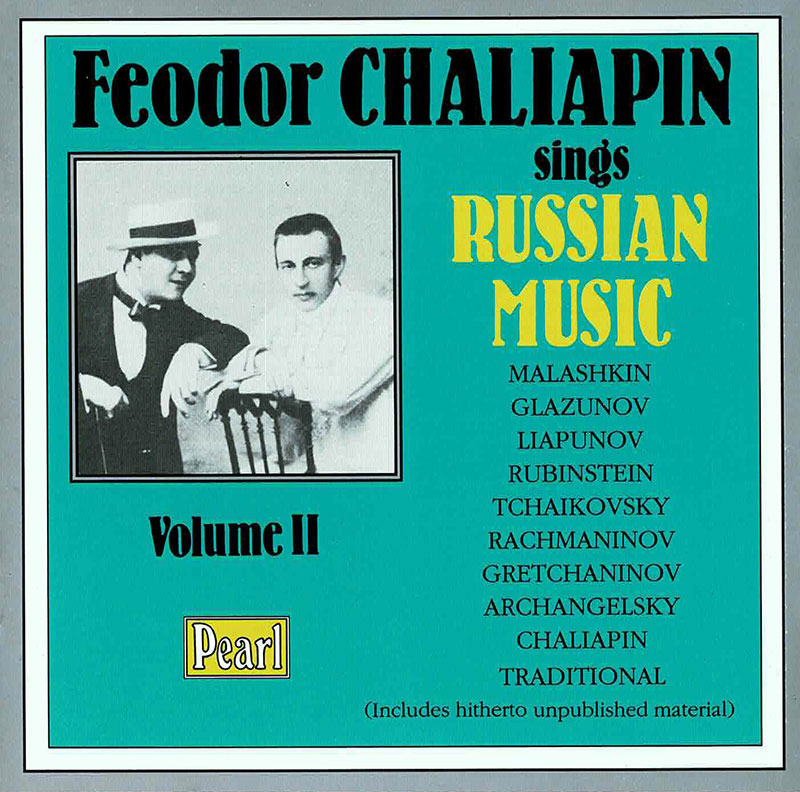

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV, RUBINSTEIN, TCHAIKOVSKY, LIAPUNOV, Feodor Chaliapin

Chaliapin sings Russian Music II

- 1. Oh, Could I in Song Tell My Sorrow for voice & piano (or orchestra)

- Composed by Leonid Dimitrievitch Malashkin

- with Feodor Chaliapin, Max Rabinovitsj

- 2. Sadko, opera Song of the Viking Guest

- Composed by Nikolay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- Conducted by Albert Coates

- 3. Songs (2) for voice & piano, Op 49 The Prophet, Op 49/2

- Composed by Nikolay Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- Conducted by Percy Pitt

- 4. The Demon, opera Do not weep, child

- Composed by Anton Rubinstein

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- 5. The Demon, opera Through the ocesan of the air

- Composed by Anton Rubinstein

- with Feodor Chaliapin, Maria Kovalenko

- 6. Persian Songs (12), song cycle, for voice & piano, Op 34 Persian love song, Op 34/9

- Composed by Anton Rubinstein

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- Conducted by Lawrance Collingwood

- 7. The Prisoner, Op 78/6

- Composed by Anton Rubinstein

- with Jean Bazilevsky, Feodor Chaliapin

- 8. The Nightingale, song for voice & piano, Op. 60/4 The Little Nightingale, Op 60/4

- Composed by Pyotr Il'yich Tchaikovsky

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- 9. I bless you, forests ("The Pilgrim's Song"), song for voice & piano, Op. 47/5 The Pilgrim's Song, Op 47/5

- Composed by Pyotr Il'yich Tchaikovsky

- with Feodor Chaliapin, Alexander Schmidt

- Conducted by Rosario Bourdon

- 10. Tale of Ivan the Terrible

- Composed by Sergei Liapunov

- with Feodor Chaliapin, Petrograd Quartet

- 11. Chanson bacchique, Op 27/1

- Composed by Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- 12. Valse de concert d'apres la Suite en forme de valse pour quatre mains, for piano (after János Végh), S. 430 (LW A318) The moon in high in the sky

- Composed by Franz Liszt

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- Conducted by Eugene Goossens

- 13. The Creed

- Composed by Alexander Andreyevich Arkhangel'sky

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- Conducted by Nicolai P. Afonsky

- 14. Two-Fold Litany, for chorus, Op. 79/6 Gloria

- Composed by Alexander Tikhonovich Grechaninov

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- Conducted by Nicolai P. Afonsky

- 15. Dark eyes ("Ochi chornye"), folksong

- Composed by Russian Traditional

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- 16. Eh, Vanka!

- Composed by Anonymous

- with Feodor Chaliapin

- 17. Song of the Volga Boatmen

- Composed by Feodor Chaliapin

- with Feodor Chaliapin, G. Godzinsky

- Feodor Chaliapin - bass

- RIMSKY-KORSAKOV

- RUBINSTEIN

- TCHAIKOVSKY

- LIAPUNOV

In his note for FEODOR CHALIAPIN SINGS RUSSIAN MUSIC- Volume 1, (GEMM CDS 9920) the writer traced the great bass's career from his origins in conditions of almost unbelievable poverty and squalor to the international eminence which he eventually achieved. That narration and related record programme in effect also charted the rise of nationalism in Russian music during the nineteenth century, as exemplified by Chaliapin in the recordings of both opera and art song which he made. Now in the Second Volume is a fascinating compilation which reflects other equally valid musical developments of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the conservatives who, inclining towards traditional Western artistic tenets, had little time for nationalist aspirations; the enigmatic figure of Tchaikovsky, with a foot in both camps, but such a colossal genius that it would hardly have mattered where he stood, and those who, branded "the second generation", blended traditional western techniques with the inheritance of their Slavonic patrimony. We continue in chronological order with the famous song by Leonid Dimitrievich Malashkin (1842-1902) O could I in song express my sorrow, an unashamed tear-jerker which Chaliapin sings with heart and soul. The recording heard here is not the familiar DA 993 of 1928, sung in English, but a hitherto unpublished version in Russian which the bass made for HMV at Hayes in 1921 during his first post-revolution recording session. The appearance next of Nikolai Andreyivich Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) is most appropriate for he, although certainly a member of the "Kutchka" or "Mighty Handful" of five composers dominated by Mily Balakirev, the Archduke of Russian nationalism in music, was the most eclectic of them. There is a bridge between him and Tchaikovsky who, conversely, was somewhat westernorientated although possessed of an unmistakably Russian musical character. Like all other members of the "Kutchka" (Balakirev worked as a railway signaller, Cui was an expert on military fortifications; the other two are discussed in the notes for Volume I); Rimsky-Korsakov was a part-time composer. His main occupation was Inspector of Naval Bands for the Imperial Russian Government. As a young man he had been to sea, and it may amuse British readers to learn that part of his Symphony was conceived with the aid of a rather inadequate piano in a pub at Gravesend, where Rimsky's ship was temporarily berthed! He joined the Balakirev circle in 1861, and met Dargomyzhsky in 1868, by which time he had already composed several significant pieces for orchestra, including the symphonic poem "Sadko" (1867) which he was to expand into his substantial opera of the same name in 1894/6 (premiered 1898). Internationally renowned though are his brilliantlyorchestrated set pieces, it was in opera that he felt perhaps most at home; there are some fifteen of them, of which "The Snow Maiden" and "Sadko" are probably the best known. From the latter work we hear Chaliapin singing the rugged Song of the Viking Guest - a gentleman who has been invited by King Neptune to a party at the bottom of the sea. Rimsky-Korsakov's output of songs was slight by comparison, and they are underrated. A good one is presented here, but the most magical of all, It is not the wind howling can be heard only on Pearl GEMM CDS 9320, in the legendary performance by that incomparable Russian tenor Ivan Kozlovsky. Although the names of the brothers Rubinstein (Anton: 1829-1894, and Nicholas: 1835-1881) may be less well remembered by posterity than Moussorgsky, Borodin, et al., their contribution to musical culture in Russia should not be underestimated. It was Anton who in 1859 founded the Russian Musical Society and, three years later, the St. Petersburg Conservatoire. In 1886 Nicholas founded the Moscow Conservatoire, the first teaching member of which was a graduate from his elder brother's establishment in the other city - Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. As Leonard points out "Naturally the conservative standards of the Rubinsteins were transplanted to the new school... the rivalry of the two music factions now became the rivalry of cities... [but] even the cities became switched around, adding to the complication.. Petersburg, itself a newly-manufactured imitation of the West, became the centre of Nationalism in music; while the old, conservative, ultra-Russian Moscow became the seat of cosmopolitan eclecticism". Tchaikovsky, thus, felt connection to both the Rubinsteins - although he had earlier in life fallen under the influence of Balakirev and is circle - and in particular to Nicholas, whose brutal diatribe against Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto is a matter of history. But let us return for the moment to elder brother Anton who was in addition to being a teacher also a prolific composer. From his opera "The Demon" (first produced at St. Petersburg in 1875) we have the Demon's two principal arias. The 'Met.' Encyclopaedia, with its uncanny knack of unearthing opera plots totally unknown to lesser mortals, reports thus: "... a score of high passion and romantic melody. The Demon, desiring Tamara, the betrothed of Prince Sinodal, has the prince murdered and pursues the girl even into a convent where Sinodal, now an angel, intervenes to bring her release in death". From Rubinstein's 125 or more songs we have here Persian Love Songand The Prisoner. Obviously Tchaikovsky has to be next, and here he is in two songs (it is curious that his considerable and distinguished output in this form is so little recognised), the titles of which are self-explanatory. (The pilgrim, by the way, is elsewhere described as 'needy'). A lesser-known but highly gifted figure in the firmament of the "second generation" of Russian composers is Sergei Liapunov (18591924), who worked both with Tchaikovsky at Moscow and Balakirev at St. Petersburg. He is best remembered for his songs and solo piano pieces, of which he wrote a great many. The Tale of Ivan Grozhny ('Ivan the Terrible') is a setting in 'folksy' style of what must clearly be a folk lyric. Our transcription is taken from an unissued special pressing. Rather larger in the "second generation" - in terms of stature, output and physical dimension! - looms the imposing figure of Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936). A child prodigy, he composed his first symphony when only sixteen, and was greatly lauded by the "Kutchka", not to mention Liszt. He gave us a sizeable legacy of superbly-crafted orchestral works, including eight symphonies - many of them rather wistful in character. In later life he became the greatly-loved Director of the St. Petersburg Conservatoire, remaining there to look after his students (he had no sympathy with the communists) until 1928, when he retired to Paris. Between 1912-15 Chaliapin was eager that Glazunov write an opera for him, but nothing came of the project; perhaps just as well, for the composer's talents lay mainly in the field of pure orchestral music. But we can hear Chaliapin representing his friend in one song: Chanson baccbique, taken from a rare HMV'Catalogue No. 2' pressing. "Let us raise our glasses to our ladyloves, to art and to sweet reason!" Mention of the name Sergei Vassilievich Rachmaninov (18731943) instantly evokes the world of the piano - and he was indeed, of course, a great composer of music for that instrument and a wonderful pianist. What seems to have been largely forgotten is his operatic connection: he was principal conductor at the Imperial Grand Theatre of Moscow between 1905 and 1906. Rachmaninov wrote two operas at around the time (one with a libretto by Tchaikovsky's brother Modest), but his first essay in this medium was Aleko, premiered at the Bolshoi Theatre in 1893, and based on a poem by Pushkin; it was his graduation exercise from the Moscow Conservatoire. As is the case with so many operas, Aleko has a rather silly plot, with gypsies, frustrated passions, etc., etc. Aleko's steamy main aria however is distinctly worth an airing-especially in Chaliapin's committed performance. Chaliapin's real attitude to the Christian faith is hard to ascertain. The emotional intensity and sheer vehemence put into the liturgical works by Archangelsky and Gretchaninov which follow are the reasons for their inclusion here. Yet... here is a little anecdote from the autobiography of HMV's great recordis tFred Gaisberg: "[Chaliapin, having been booked for a recital, but being incapacitated through laryingitis] in despair threw himself on the bed and moaned 'Bozhe, Bozhe, what have I done to deserve this?' He paced the room, knocking his head against the wall and again cried to God 'Why should I be so punished?' Then suddenly Nicolai, his little valet, said in Russian'Feodor ivanovich, go to the concert; God will give you back your voice when the moment comes'. Chaliapin stopped short and, with a look of scorn at the valet, said 'What has God got to do with my voice!"'. Three favourite Russian folk songs follow by way of encores, and it is difficult to imagine that any detailed comment on them is called for. The Song ofthe Volga Boatmen, made in Tokyo in 1936 is, incidentally, the very last record made by Chaliapin. CHARLES HAYNES