Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

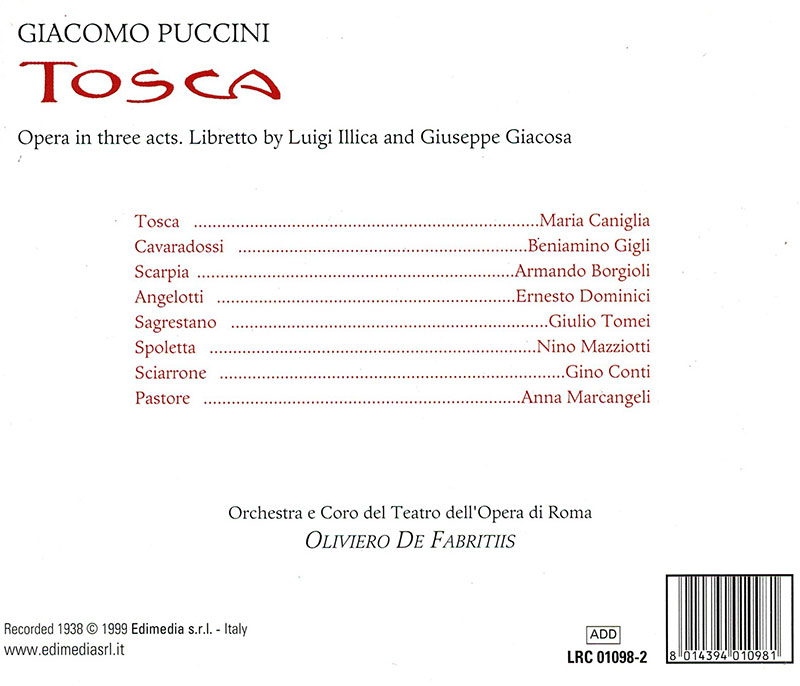

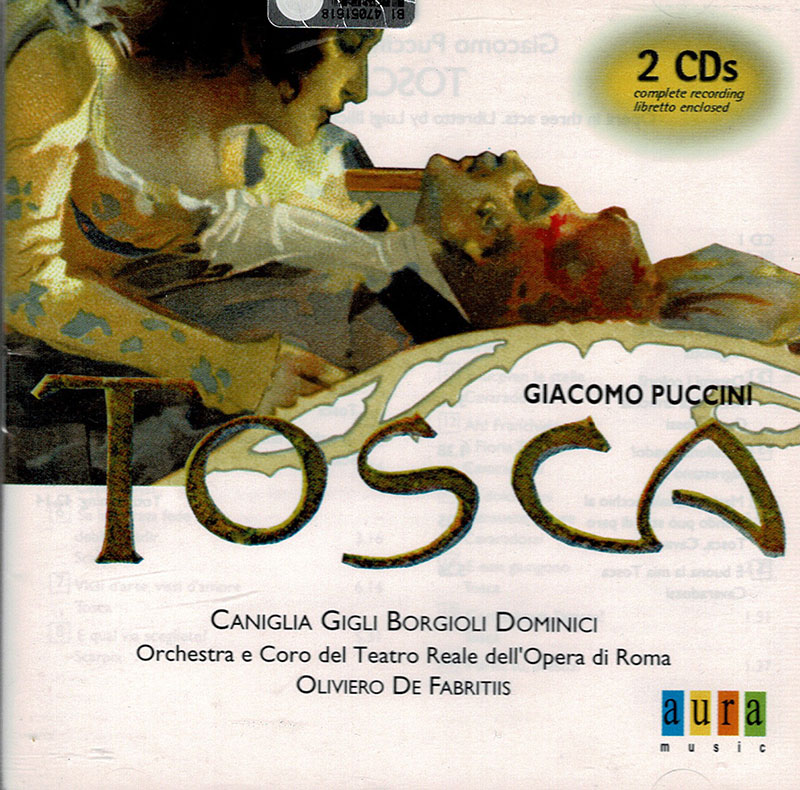

PUCCINI, Beniamino Gigli, Maria Caniglia, Oliviero de Fabritiis, Orchestra e Coro del Teatro dell'Opera di Roma

Tosca

- 1938 Oliviero de Fabritiis

Although a photograph of Maria Caniglia (presumably as Tosca) adorns the cover of this Naxos re-issue, there is no doubt as to who dominates the performance itself. Gigli was at the height of his powers at this time, the leading dramatic-lyric tenor of the day, and the natural heir to Caruso. By the time this celebrated recording was made in 1938, Gigli had been singing Cavaradossi for nearly twenty years, and it shows. Apart from the truly glorious quality of the voice itself, he invests the character with warmth, humanity, and even humour (where appropriate), a difficult balancing act that can only come from real familiarity with the role. Even though one approaches historic recordings with some caution (certainly regarding sound quality), I was initially disappointed with what I heard here. Puccini’s dramatic opening, with its rasping trombones outlining the theme later to become the ‘Scarpia’ motif, should leap out of the speakers and grab you by the throat. Here, a rather distant, sourly tuned pit orchestra struggle to make any sort of impact. Things improve markedly when the Sacristan makes his first entry, and even more so when the power of Gigli’s voice is first encountered. So it becomes more of an issue of balance, with the singers given a forward prominence over the orchestra, and you soon adjust. Many later opera producers still like to balance this way, and, for a 1938 vintage, the voices are captured with excellent clarity and realism. So forget about encountering too much of Puccini’s wonderful woodwind detail, or hearing the inner horn and string voicings (as you do in Karajan’s classic Decca version). Revel instead in listening to a truly Italian verismo tradition, where the high tessitura holds no fears, and the singers perform as to the manor born. Caniglia was a famous Tosca in her day, and gives a characterful rendition of the eponymous heroine. She may lack the dark toned, sexy allure of Leontyne Price (for Karajan) or the sheer spine-tingling drama of Callas (for Victor de Sabata on EMI), but this is a convincing portrayal, if a little shrill in places. She does not spit venom, as Callas does, at Scarpia’s advances, but her sincerity is moving in its own way. ‘Vissi d’arte’ is sung with total honesty, but at a rather forceful level throughout; Price is exemplary here. Borgioli sang in all the world’s great opera houses (including the Met.), and knew Gigli well, so there is plenty of interaction when required. He is slightly wooden in places (as when he prepares to interrogate Cavaradossi), but the voice has a firmness and richness that are very satisfying – try his famous first entry in the church. As mentioned before, the set really belongs to Gigli, whose voice is magnificent. ‘Recondita armonia’ soars in a thrilling way that is rare on disc, and we can forgive him his famous over-acting in places (such as the melodramatic torture scene). Hearing this voice makes one agree with the gloom merchants, who say that the great days of Italian tenors are over. The conducting is workman-like rather than inspired, and once one is used to the balance, the sound is enjoyable enough. The highlights of the French Tosca are interesting for Ninon Vallin’s portrayal, but with a poor Cavaradossi (Enrico di Mazzei) and terrible sound (even Ward Marston has to admit to not being able to rescue this), it’s one for the specialist only. (...) Tony Haywood