Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

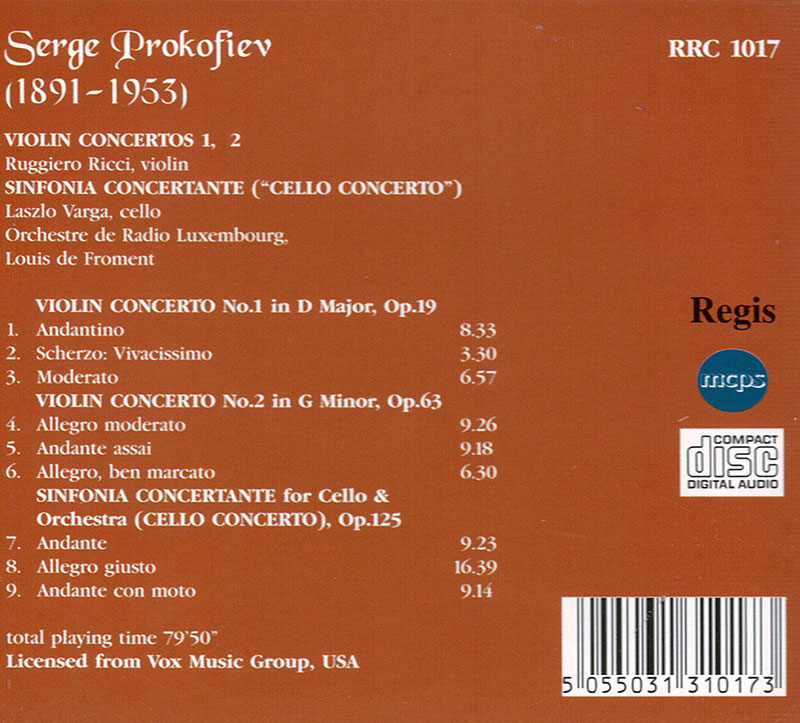

PROKOFIEV, Ruggiero Ricci, Laszlo Varga, Orchestra of Radio Luxembourg, Louis de Froment

Violin Concertos 1, 2 / Sinfonia Concertante for Cello & Orchestra

- VIOLIN CONCERTO No.1 in D Major Op. 19 1.

- 1. Andantino 8.33 2.

- 2. Scherzo: Vivacissimo 3.30

- 3. Moderato 6.57

- VIOLIN CONCERTO No.2 in G Minor Op.63

- 4. Allegro moderato 9.26

- 5. Andante assai 9.18

- 6. Allegro, ben marcato 6.30

- SINFONIA CONCERTANTE for Cello & Orchestra

- (CELLO CONCERTO No.2 revision), OP. 125

- 7. Andante 9.23

- 8. Allegro giusto 16.39 '

- 9. Andante coca moto 9.14 ,

- total playing time 79'50'.

- Ruggiero Ricci - violin

- Laszlo Varga - cello

- Orchestra of Radio Luxembourg - orchestra

- Louis de Froment - conductor

- PROKOFIEV

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) emigrated to the West in 1918 settling in Paris two years later, but decided to return to the Soviet Union in 1933. The two Violin Concertos therefore flank his period of self-imposed exile whilst the Sinfonia Concertante, although in many ways an adaption of an earlier work, belongs to his late period. The timing of his return unfortunately coincided with the onset of 'socialist realism' and Prokofiev was among the composers severely criticised in 1948 for `formalist tendencies'. He died on the same day as Josef Stalin. The First Violin Concerto in D major opus 19 was composed in 1917 at around the same time as the Classical Symphony, and shortly before Prokofiev started work on his Third Piano Concerto. It received its first performance in Paris in 1923. Not being immediately popular, it required the enthusiasm of Szigeti to bring the First Violin Concerto to a worldwide audience. The first movement is typical of its composer, being a string of episodes superbly held together with the magical opening theme returning to be played on the flute with solo violin, harp and muted string accompaniments - one of the most glorious passages in all Prokofiev's oeuvre. The second movement is a dazzling scherzo-rondo whilst the third movement has something of the opening movement's lyricism and the middle movement's virtuosity. To violin trill accompaniment, the opening theme returns towards the end and gradually becomes somewhat impressionistic. The orchestra is not of unusual size but features an important role for the tuba during the final movement. The Second Violin Concerto in G minor opus 63 was commissioned by the French violinist Robert Soetens whilst the composer was still living in Paris but belongs to the group of works composed shortly after his return to the Soviet Union, being completed in 1935. Its sound in many ways resembles the work that immediately followed: Romeo and Juliet. The opening gloomy passage from the solo violin soon gives way to a tender second subject whose throbbing string accompaniment is reminiscent of so much of the Romeo and Juliet ballet score. The charming slow movement demonstrates Prokofiev at his most childlike. The 12 / 8 rhythm allows ample scope for tricky figurations whilst the orchestra provides a strumming accompaniment. An unexpected and brilliant touch comes shortly before the movement's close when the soloist and the orchestra swap roles. The third movement is a coarse peasant-like dance-Rondo that recalls briefly main themes from the preceding movements in the manner of earlier concertos. In many ways this concerto is the more traditional of the two violin concertos, using a smaller orchestra and with a movement pattern of fast / slow / fast reminiscent of similar works of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, whereas the First Just prior to Prokofiev's return to the Soviet Union from Paris he began work on a Cello Concerto but put it aside, completing it five years later. This concerto, his opus 58, was first performed in 1938. The young cellist Mstislav Rostropovich (born in 1927) played this concerto in the composer's presence in 1947 and it was decided that Prokofiev should rewrite the piece especially, with Rostropovich in mind. Once again, Prokofiev's work was delayed, this time by ill health, and Rostropovich found it necessary to stay with the composer for extended periods in 1950 and 1951, giving technical advice and playing passages as they were written. In 1949 Rostropovich and Sviatoslav Richter had premiered Prokofiev's Cello Sonata; they now both contributed to the premiere of the new work Sintonia Concertante opus 125 (dedicated to Rostropovich) for it was in this concert (18 February 1952) that Richter made his conducting debut. The Sinfonia Concertante, basically an extension of the Cello Concerto, with more virtuoso solo writing to correspond to the character of its dedicatee, is of longer length but is also less dissonant than its predecessor. The lyrical first movement has two principal themes, the first played by the soloist and the second, more poignant, by the violin section. The much more substantial and emotional second movement has towards the beginning a long unaccompanied passage for the soloist as well as a cadenza later in the movement. At key moments the composer gives the soloist alternative passages to play but refrains from making them `simpler' (Prokofiev felt that this might hurt the soloist's vanity!). A set of variations forms the generally vivacious final movement. The American violinist Ruggiero Ricci was born in 1918 and made his debut in San Francisco at the age of ten playing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, and appeared in New York with the same work the following year. Although renowned as a fine interpreter of the whole solo violin repertoire, he has perhaps been best known for his recordings of Paganini and of twentieth century compositions. Since 1975 he has taught at the Juilliard School. The Hungarian Lazslo Varga, now Professor of Cello at Houston University, began his career playing under Toscanini and in the 1950s became Principal Cellist of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. A renowned recording artist, he has been labelled 'a cellist's cellist' by the New York Times. He has also been a member of the Borodin Piano Trio. © 2000 James Murray, Newquay