Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

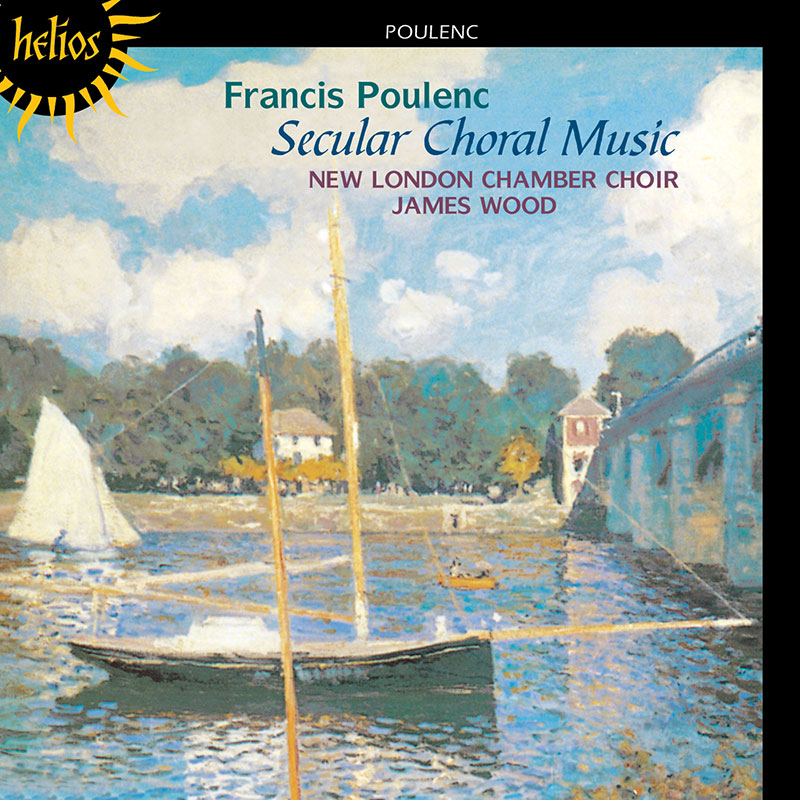

POULENC, New London Chamber Choir, James Wood

Secular Choral Music

- Contents:

- 1. Un soir de neige De grandes cuillers de neige [1'13]

- 2. La bonne neige [1'29]

- 3. Bois meurtri [2'19]

- 4. La nuit le froid la solitude [1'03]

- Chansons françaises

- 5. Margoton va t'a l'iau [2'07]

- 6. La belle se sied au pied de la tour [1'56]

- 7. Pilons l'orge [0'40]

- 8. Clic, clac, dansez sabots [1'42]

- 9. C'est la petit fill' du Prince [5'47]

- 10. La bell' si nous étions [1'09]

- 11. Ah! mon Beau Laboureur [3'52]

- 12. Les tisserands [1'40]

- Sept chansons

- 13. La blanche neige [1'03]

- 14. A peine défigurée [1'34]

- 15. Par une nuit nouvelle [1'09]

- 16. Tous les droits [2'37]

- 17. Belle et ressemblante [2'05]

- 18. Marie [1'45]

- 19. Luire [1'52]

- 20. Chanson à boire [3'16]

- Petites voix

- 21. La petite fille sage [1'44]

- 22. Le chien perdu [1'13]

- 23. En rentrant de l'école [0'36]

- 24. Le petit garçon malade [1'58]

- 25. Le hérisson [0'45]

- Figure humaine

- 26. De tous les printemps du monde [2'43]

- 27. En chantant les servantes sélancent [1'52]

- 28. Aussi bas que le silence [1'36]

- 29. Toi ma patiente [2'00]

- 30. Riant du ciel et des planètes [1'04]

- 31. Le jour m'étonne et la nuit me fait peur [1'34]

- 32. La menace sous le ciel rouge [4'02]

- 33. LIBERTÉ [4'12]

- New London Chamber Choir - choir

- James Wood - conductor

- POULENC

Un muy bonito disco' (Ritmo, Spain) 'Strongly recommended!' (Fanfare, USA)During his lifetime Poulenc was probably best known for his frivolous piano pieces. His fondness for writing such light-hearted and inconsequential music no doubt stemmed from the incident which he claimed first inspired him to embark on a career as a composer: as a young boy he had put a handful of centimes into a pianola and was utterly captivated by the charms of a piece of typical salon music (by Chabrier) which emanated from the machine. His father, a devout Catholic and wealthy businessman (the family firm of pharmaceutical manufacturers exists today as the massive Rhône-Poulenc corporation), wished his son to pursue a traditional musical education but with his own death in 1917 and François’s rejection from the Paris Conservatoire the same year the eighteen-year-old Poulenc began to rebel against both the French musical establishment and, to a lesser extent, the Catholic faith. In this he was certainly not dissuaded by his mother, herself an accomplished pianist and an eager Paris socialite. Indeed it was his mother who gave him his earliest music lessons and, apart from some further piano tuition from Ricardo Viñes, he received no real formal musical education until, on completing his period of obligatory military service, he was taken on as a composition pupil by Charles Koechlin, with whom he studied from 1921 to 1924. It was Koechlin who instructed him on writing for voices and enabled him in 1922 to compose his first choral piece Chanson à boire, a setting of an anonymous seventeenth-century text in praise of drink. Scored for four-part male choir this is typical of what might be described as Poulenc’s ‘hooligan’ tendency, degenerating in the final bars into an outrageous imitation of drunkenness. It was rather unfortunate that he chose this particular text since the Harvard Glee Club, for whom it was written, were banned from performing it during the period of Prohibition then sweeping America.