Logowanie

TYDZIEŃ z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

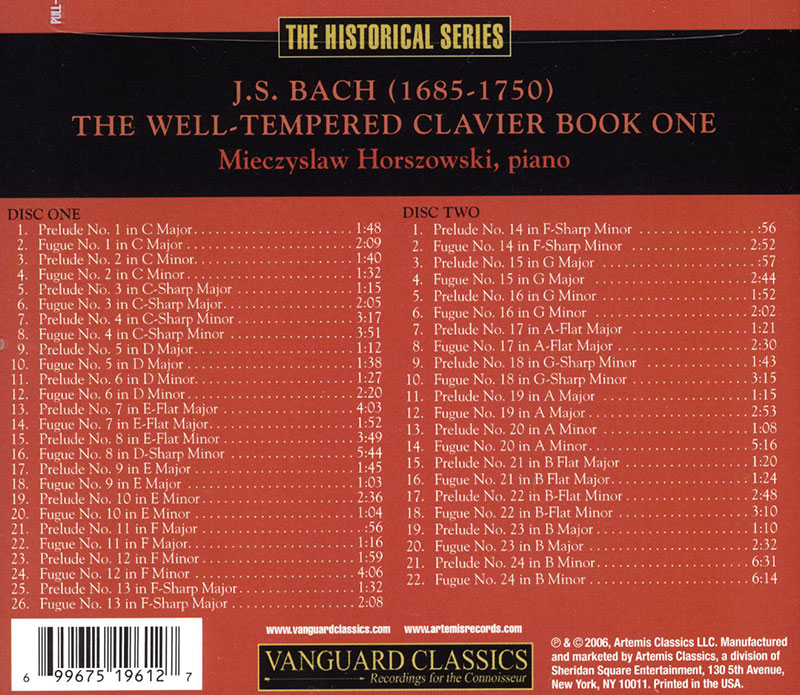

BACH

The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book One

Throughout his life Mieczyslaw Horszowski performed the concertos and sonatas of Mozart, by choice. Bice Horszowski Costa, his widow, points out that he played the Concerto No. 26 "Coronation" early on, "in the last century". The first great interpreter to programme more than a few of these works was Ferruccio Busoni, who in 1921 gave a series of the concertos in Berlin, adding five more to his repertoire of six. Perhaps Horszowski heard Busoni's Mozart, for he idolized his playing and recalled with fascination performances he attended. Due to Busoni's efforts, more attention was given to this neglected area of the literature, as Schnabel, Fischer and Horszowski began to play many of them. Two pianists who gave a cycle of concertos while conducting from the keyboard were Edwin Fischer and Erno Dohnanyi. The interpretations of these masterpieces reached high points in the art of Schnabel, Fischer and Horszowski. Horszowski approaches these works in a unique manner, as he shapes the piano's tone during exposed solo passages to resemble a wordless singer declaiming the music as if intoned by an abstract medium. During tutti passages the playing changes as it embeds itself within the musical activity, attesting to Horszowski's lifelong mastery of chamber music. The vision he and Waldman project of the composer's works is that of a terrestrial paradise, in which exactitude and the utmost refinement and sensitivity create a world unto itself. Once when I thanked him after his having played two infrequently performed concertos, Horszowski observed "Not one note can be added to make them better". Throughout his life Horszowski disdained publicity and ignored requests to write his biography but one day it will be reconstructed, as his anecdotes have been notated and diaries exist. Horszowski's life and times may be understood by drawing attention to significant colleagues with whom he collaborated and shared ideas: Frederic Waldman and Józef Wittlin. At the time of writing, Maestro Waldman has retired from active conducting and although he has passed his ninetieth birthday, he attends Columbia University, studying art history. The last meeting he had with Horszowski was passing, on a New York street. Horszowski spoke of his poor vision; " I regret losing my eyesight for only one reason - I cannot learn new works". The two had performed Mozart's concertos many times over a twenty year period. Waldman fondly spoke of rehearsals as truly memorable experiences, for Horszowski was engaged in the music as though he were playing chamber music, accommodating all the orchestra's soloists. The ideal collaboration Waldman provided in these concertos brings out another essential element to these concertos. Horszowski's angelic and boldly defined playing is matched by a transparency in the orchestra which is far removed from the slick and homogenized Mozart we so often hear. Waldman stresses the complexity of the composer's orchestration. As Mozart did not have large forces available, he created the illusion of a grander ensemble by giving the winds and horns greater independence from the string section, rather than attempting to blend them into the body by doubling parts. Waldman preserves their autonomy, allowing one to experience the music in all its complexity. This manner of sculpting the sound rather than seeking to reduce it to a veneer (often the case today) does justice to the largeness of the composer's conception and proves how innovative Mozart's orchestral writing could be. Waldman's and Horszowski's differing approaches complement one another, effectively transcending the commonplace roles of soloist and orchestra. Behind Waldman's conducting is a rich background. As a youth in Vienna he heard Furtwangler lead all nine Beethoven symphonies, Nikisch "accompany" the debut of Erica Morini, the pianism of D'Albert, Busoni (playing Beethoven's 4th concerto), Rosenthal, Carreno. He conducted opera in Danzig and for a prince's own theatre in Gera. He attended rehearsals for the premiere of Berg's Wozzeckby Erich Kleiber, which impressed him more than the performance. In the 1920s Waldman spent time in Berlin. In 1930 he began work with the Deutsche Musik Buhne, a group funded by the Ministry of Culture to travel to cities and towns without orchestras. He gave operas such as Handel's Rodelinda, Hansel and Gretel, Nozze di Figaro and met Richard Strauss while he rehearsed intermezzo. Otto Klemperer offered Waldman the position of 1st Kapellmeister with the Kroll Opera in 1934. The events of the preceeding year were such that like Klemperer, Waldman left Germany. In New York he ran the opera programme at Juilliard, recorded works by Varese with the composer's supervision and gave the world premiere of Messiaen's From the Canyons to the Stars. The choice of Horszowski as soloist came about unintentionally. Musica Aeterna represented a concert series in which works from the late Baroque onward, "music forgotten and remembered", were frequently performed at the Metropolitan Musician of Art in New York. The series was funded by the late patroness Alice Tully, who allowed Maestro Waldman complete freedom in choosing repertoire and soloists. He once gave a rare performance of Rossini's Petite Messe Solennelle. Soloists in his concerts included Horszowski, Arrau, Casadesus, Curzon, Bachauer, Milstein, Morini, Szeryng and Francescatti. In 1962, Dame Myra Hess had to cancel her projected cycle of ten Mozart concertos due to an illness which became fatal. Waldman immediately thought of Horszowski and phoned him: "Can you play ten Mozart concertos next season?" "Which concertos?" [Waldman listed them] °I know seven of them. I will learn the other three." Some of the performances were broadcast on the radio. One of Waldman's students had access to a disc cutting machine and had recordings made of the concerts directly from the hall's microphones. With their long overdue publication, these concerts will no longer lie undisturbed on Maestro Waldman's library shelves. One of Horszowski's closest friends was the Polish-American writer Józef Wittlin (18961976). Wittlin attended most of Horszowski's Mozart recitals, the fourteen concertos given with Maestro Waldman and Musica Aeterna as well as the four evenings in which Horszowski performed all seventeen sonatas. He rarely failed to send Horszowski a note informing him of his intended presence or, following the performance, a few lines expressing his delight and gratitude, as it was more than a gesture of etiquette, but important for both to remind each other of their reciprocal attention to one another's an and a way of honouring the esteem and friendship they shared. Wittlin studied philosophy in Lwów, Horszowski's birthplace, and afterwards in Vienna, where he befriended the remarkable and short-lived writer Joseph Roth, who hailed from the eastern-most frontier of Galicia near the border with Ukraine, the end of Europe. Before the Germans obliged Wittlin and his family to escape from Poland they lived in Warsaw, where he belonged to a literary circle including Witold Gombrowicz and Bruno Schutz. As Horszowski occupied a significant role in the music world and was the last pianistic genius from Poland, Wittlin and his circle constituted the final generation of Polish intelligentsia before murder by the Nazis, exile and the censorship of a Communist regime halted its development. Wittlin's background included the classics but his becoming drawn to Homer came after experiencing duty in the First World War. One of his early works was a translation of The Odyssey into Polish in 1924. He was not satisfied with it and made two more full revisions of the translation in 1935 and 1957. Horszowski possessed all three editions and read them, an indication of his interest and of having maintained a language from a country he left before the age of seven. Among the final poems composed by Witdin is his reflection on Mozart. An expressionist, Wittlin became obsessed with death at the end of his life. One trait he shared with Horszowski was what his daughter describes as miniloquence - the importance of small things, of silence. The following poem was inspired by the contact Wittlin had with Mozart through Horszowski and was posthumously dedicated by the poet's widow to Horszowski. It is unpublished, and we express our gratitude to Elizabeth Lipton, Wittlin's daughter, for her permission to publish her literal translation. © 1994 Allan Evans