Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

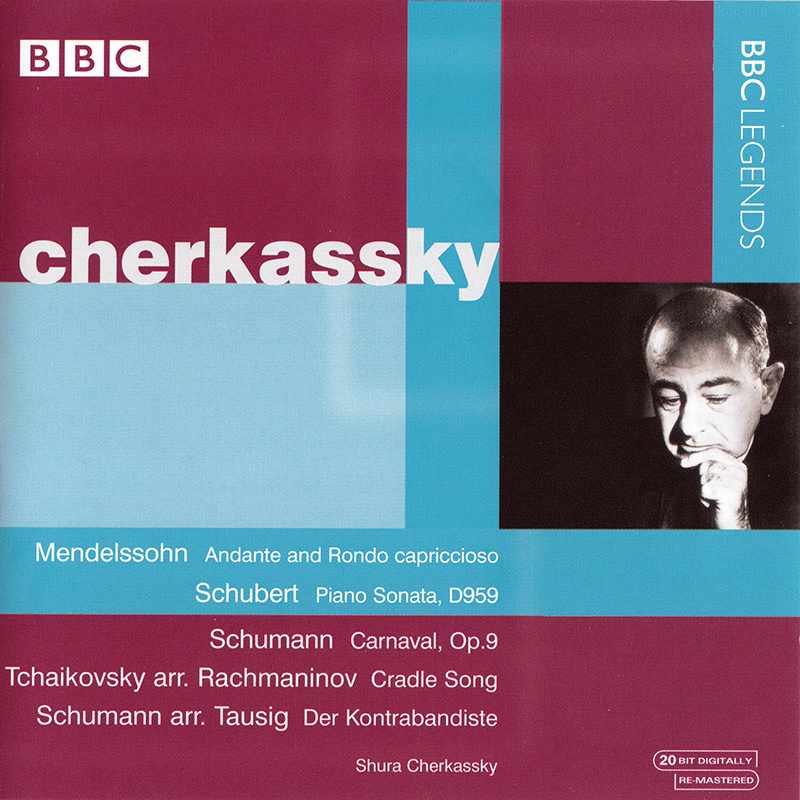

MENDELSSOHN, SCHUBERT, SCHUMANN, TCHAIKOVSKY, Shura Cherkassky

Andante and Rondo capriccioso in E Major / Piano Sonata in A Major, D. 959 / Carnaval, Op. 9 / Der Kontrabandiste

- Shura Cherkassky - piano

- MENDELSSOHN

- SCHUBERT

- SCHUMANN

- TCHAIKOVSKY

Celebrating the Shura Cherkassky (1909-1995) centennial, as well as the Mendelssohn bi-centennial year, this Queen Elizabeth Hall, London recital, 1 November 1970, opens with a beguiling, transparently lyrical performance of Andante and Rondo capriccioso in E Major, Op. 14, which after a tuneful first part, renders the Rondo in fleet figures whose kinship with A Midsummer Night’s Dream cannot be denied. Schubert only attracted Cherkassky with two of his A Major sonatas, the D. 664 issued by Decca, while it was World Record Club that inscribed the late A Major in 1960, never reissued in CD format. Cherkassky plays the A Major first movement as a study in contrasting textures and color dispositions, the runs and ostinati acting as intermezzos between periods of melancholy, tender reflection. Ever the Cheshire Cat in music, Cherkassky seems more concerned with touch, left-hand articulation, and dynamic coloration than with logistics and architecture, since the movement meanders, its mood swings fascinating because of Cherkassky’s active palette. Cherkassky imparts a delicate mystery to the Andantino, like his esteemed teacher, Josef Hofmann, the fingers lithe dragonflies. The dark middle section–contrapuntal in the style of a Bach fantasia–basks in the Cherkassky resonance, although the ethos seems skewed. The da capo has the plaintive melody set over a fateful dirge and trill, here given the Godowsky treatment in color stretti. Brisk, agile figures mark the Scherzo, tantalizing and coy, played as etude in non-legato. The last movement is all the old Cherkassky magic, especially in degrees of jeweled pianissimo. Flowing melody and exalted stretti mark every page, a colossus of nuanced beauty and sheer, tonal relaxation. The willful, whimsical sides of Cherkassky’s character range freely in Schumann’s beloved Carnaval suite, a dramatically precocious performance, played for speed, elan, and crisp expression of the composer’s theatrical personae, many of which derive from anagrams of his name and his town, Asch. For the repeats, no melodic line appears in its guise verbatim; always, some slight nuance, metric pulse, or accent finds its way to the shimmering surface. The Commedia dell’arte figures, Pierrot, Arlequin, and Coquette prance even as they pout. The Valse noble reveals contrapuntal subtleties we have missed countless times. A leisurely Eusebius allows the left hand to intimate the “little scenes on four notes” or “Papillon” and “Dancing Letters” motifs that permeate these fanciful, masked ball revelers who eventually march against anti-cultural complacency. Florestan seems rather impetuous, though his throes break off into a confrontation with a skittish Coquette. Replique tugs at time values and offers the Cherkassky color panoply. Then the passions enter, first in the form of an ardent Chiarina, to be followed by an erotic nocturne, Chopin. The repeat illuminates the left hand sforzati with a hand Scriabin would admire. Estrella haughtily appears and disappears, leading to the brilliant Reconnaisance study, whose own second section takes on some deeper chiaroscuro we will hear later in the composer’s Symphonic Etudes. Frisky lightness defines the Pantalon et Columbine interlude, the da capo of which becomes wildly vivid. A Viennese gait graces Valse allemande, only to yield to the feverish exploits of Paganini, whose bariolage technique waxes supple and demonic. The returned Valse exploits numerous rhythmic indulgences, all of tem easily forgiven. Aveu moves impatiently, anticipating the big, rhetorical gestures in Promenade. Pause moves with lightning speed, calling the Davids-League to arms, resilient and inspired, the responsive audience enchanted. Not on the recorded program is the Hungarian Rhapsody No. 15 of Liszt; but we do receive the two encores, the first of which is Tchaikovsky’s Cradle Song, Op. 16, No. 1 in Rachmaninov’s transcription, a water-piece that splices the lied form with a touch of the nostalgic ballade. Schumann’s The Smuggler (Dar Kontrabandiste) used to be a strong Grant Johannessen encore; no less kaleidoscopic under Cherkassky, the bravura piece blazes in runs, repeated notes, and quicksilver shifts in register. –Gary Lemco