Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

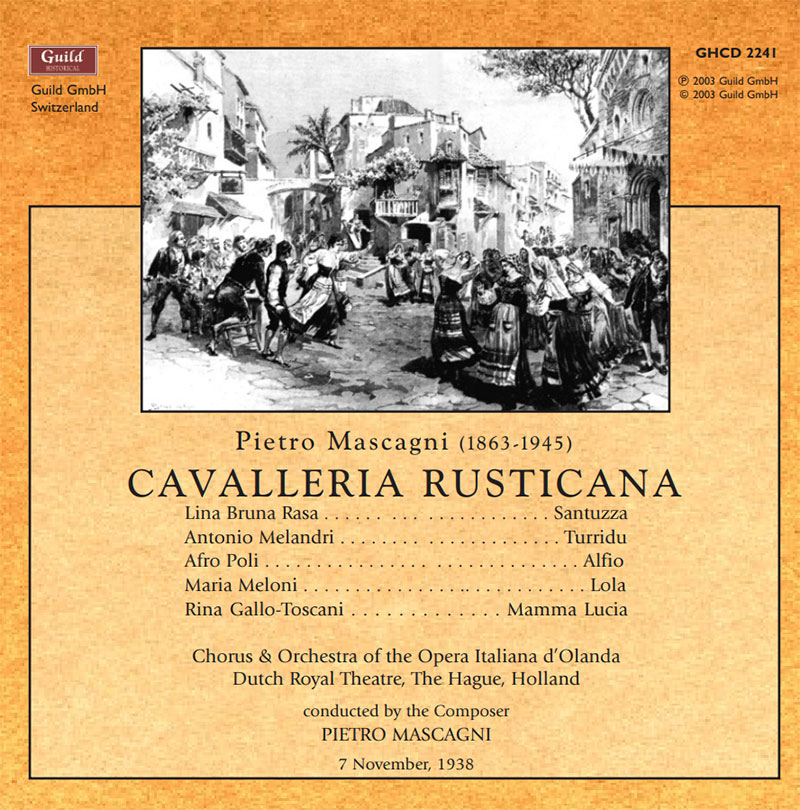

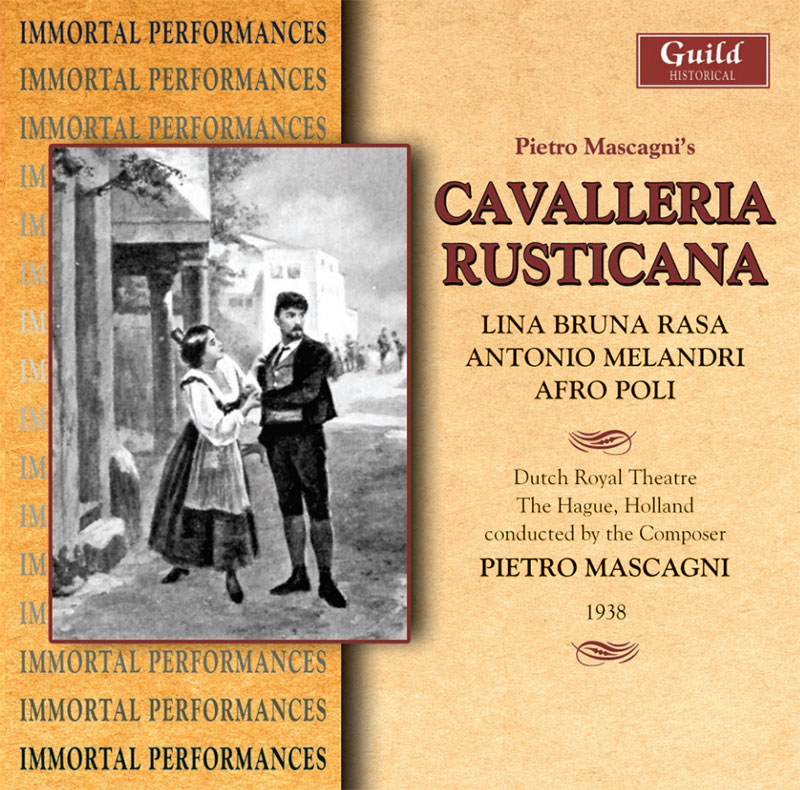

MASCAGNI, Lina Bruna Rasa, Antonio Melandri, The Dutch Royal Theatre The Hague, Pietro Mascagni

Cavalleria Rusticana - 1938

Cavalleria Rusticana by Pietro Mascagni 1938 conducted by the Composer - Dutch Royal Theatre Hague Holland This is the performance through which one can hear why Lina Bruna Rasa was the composer's favorite Santuzza fiery, overwhelmingly dramatic, her singing wont soon be forgotten. Equally impressive is the conducting of the composer vital, propulsive, rich with atmosphere so different than his leadership in the disappointing HMV commercial recording, so well known to opera lovers. The tenor gives a memorable rendition of Turridus farewell one of the most effective on record all heard in sonics immensely rich for the source and year. Although the recording is afflicted with certain defects, the excitement, the élan of this performance will grip you from start to finish. Dont miss it! GHCD 2241 ------------------------------------- MusicWeb Friday May 16 03 Pietro MASCAGNI (1863-1945) Cavalleria Rusticana - Melodrama in one act. Santuzza, Lina Bruna Rasa (soprano). Turridu, Antonio Melandri (tenor). Alfio, Afro Poli (Baritone). Lola, Maria Meloni (soprano). Mamma Lucia, Rina Gallo-Toscani (m. soprano). Chorus and Orchestra of the Opera d’Olanda Dutch Royal Theatre, The Hague, Holland. Conducted by the composer, Pietro Mascagni. Recorded live 7th November 1938 GUILD HISTORICAL GHCD 2241 [78.36] Mascagni conducted a number of his works in the theatre and on record. Being the composer of a highly successful work does not, however, necessarily confer the ability to draw out the best performances of one’s own work. Indeed, Mascagni’s studio recording of this work, made in 1940 with the same soprano, his favorite Santuzza, and Gigli as Turridu, is renowned for dilatory tempi and some sloppy ensemble (Naxos Historical). In this, and other known theatre performances, his beat and rhythms were much more dynamic and the theatrical impact considerable. In this recording his timing, including applause beats Sinopoli, no slouch, on his 1989 recording (DG) featuring Baltsa and Domingo, each thrilling in their roles. Live recordings do, however, have their downside in respect of recording quality, stage noise and the intrusion of applause. In this issue, all these factors, and surface noise (tr.16), play a part in limiting one’s enjoyment of a vibrant, well sung, dynamic performance. In the prelude the harp is clearly heard, but here, and elsewhere, the strings lack presence and depth, making the recorded texture sound rather ‘heavy’. Audience coughs and stage noise as well as applause is to a degree intrusive. The effect of such intrusions can be mitigated, in the overall assessment, if compensations are to be found elsewhere, and certainly that is so in the performance of Lina Bruna Rasa as Santuzza. Born in 1907 her fragile psychological state limited her career, but in this performance one or two pitch lapses apart, her vibrant and dynamic representation of Santuzza’s moods is formidable. Nowadays we are used to creamy even vocalization that often forgets that verismo isn’t just beauty of tone but real life; the life of love, anger and hate and these are the characteristics that blaze out in this interpretation (trs.4 and 11). As her lover, Melandri is rather thick-toned and baritonal in timbre. He created Falco in Mascagni’s ‘Isabeau’, and recorded Mefistofele and Fedora for Columbia. On stage he sang Radames, Samson and Cavaradossi, all big voiced roles and this is what he gives here. He lacks the finesse of Gigli on the studio recording, but his characterization is strong and appropriate, particularly in his duet with Santuzza ‘Ah! Lo vedi’ (tr.11) which is hair-raising in its dramatic intensity. Afro Poli as Alfio is the kind of baritone that used to ‘grow on trees’ in Italy. Strong of voice with well covered and colored but virile tone, he sang Marcello in the 1938 HMV recording of La Boheme with Gigli as Rodolfo. His way with words (tr.5) conveys clearly what Turridu is up against, did he but know it, by dabbling with his wife. Lola, by the way, is sung with clarity but little distinction by Maria Meloni. The fact that the cast are native speakers is a great benefit to the performance. Richard Caniell provides his usual informative biographical and performance notes as well as information on the recording sources including details of the interpolation of some of Melandri’s lines, from a 1930 performance, that would otherwise be missing. Robert J Farr