Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

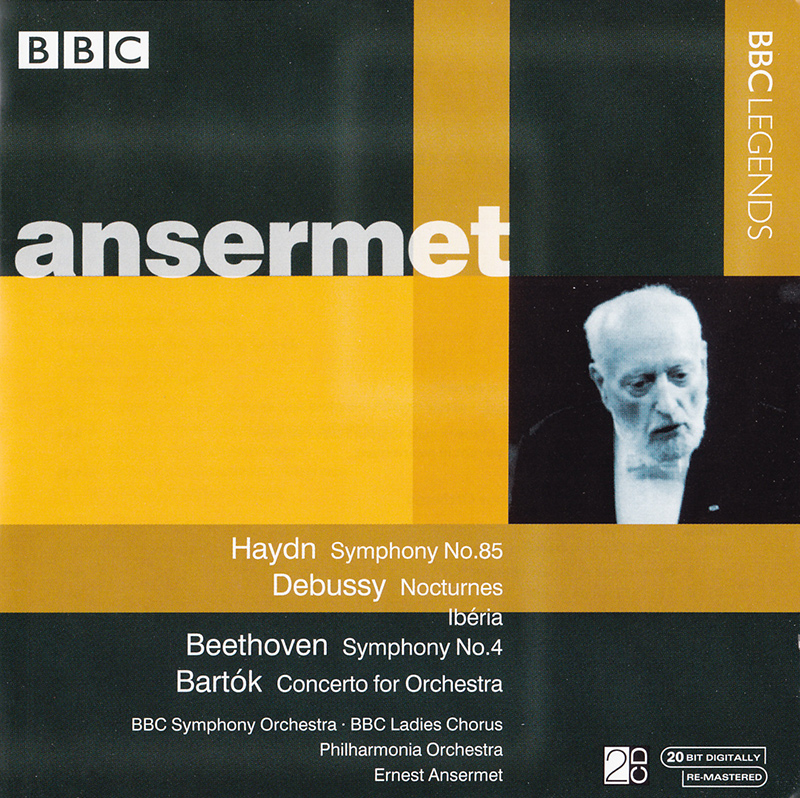

HAYDN, DEBUSSY, BEETHOVEN, BARTOK, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Ernest Ansermet

Symphony No. 85 in B-flat Major / Three Nocturnes / Symphony No. 4 in B-flat Major, Op. 60 / Concerto for Orchestra

- BBC Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- Ernest Ansermet - conductor

- HAYDN

- DEBUSSY

- BEETHOVEN

- BARTOK

A catholic mix of musical styles from Swiss-born Gallic conductor Ernest Ansermet (1883-1969) graces these two discs from the BBC. Mathematician as well as musician, Ansermet eschewed romantic sentimentality in his interpretations, preferring the clear, understated style he admired in Felix Weingartner. In his execution of the so-called “pairs” section of Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra (28 August 1958) from Edinburgh, for instance, we can hear a precision and intervallic clarity of articulation between clarinet, flute, harp and brass, as well as the later string and percussion riffs that well point to the deconstructionist character of Pierre Boulez. Yet, when the shrouded, emotional grandeur of the funereal Elegie breaks forth, we feel a tragic restraint that becomes quite gripping. Under Ansermet, we feel Bartok’s synthesis of Hungarian impulses with Debussy’s subtle coloration, always expressive, anguished, and potent. Shostakovich devolves into a circus parody in the Intermezzo interroto, yet the haunted melody, with plucked accompaniment manages a weak smile. Roumanian hora and maruntel flash by in kaleidoscopic array for the moto perpetuo Pesante–Presto, with its truncated fugato and digs at Javanese gamelan music. A rousing performance, and recall the music itself was a mere 15 years old! The program begins with a muscular rendition of Haydn’s Paris Symphony B-flat Major, No. 85 (2 February 1964), with its propulsive rocket figures, all sturm und drang. Large arches and strong cadences remind us how close this music is to the F Minor Symphony “La Passione.” Nice work from the BBC oboe throughout. A carefully shaded rubato infiltrates the stately procession for the Romanze and its wonderful flute variant. The Menuetto urges us along with its accented sforzati and grace notes, a trio of galant, old-world dignity. The Finale: Presto is one of those hybrid rondo-sonata forms Haydn invented, intensely dense melodically and rife with woodwind colors. A great Debussy exponent, Ansermet lavishes graduated mysteries on the Trois Nocturnes (2 February 1964), of which Nuages shimmers with erotic suggestion. My own favorites in this piece are Desormiere, Beinum, and Stokowski. Frolic and pageantry in Fetes, banners wafting under a dark sky. Harp and woodwinds mix with wordless women’s chorus in Sirenes, but the waves, too, exert a beguiling summons. Iberia (28 August 1958), on the other hand, relishes an assertive brightness missing from Debussy’s three grisailles, his studies in gray. Even the Perfumes of the Night prove restive, musical Rita Hayworth, seeking to intoxicate any and all. Festival-day morning basks in Dionysiac revelry and color, those shimmering strings achieving the same definition Ansermet demanded in Stravinsky’s Firebird performances. In his interview on the disc with Robert Chesterman, Ansermet recalls having observed Debussy’s conducting the premier of Rondes de Printemps and then going backstage to meet him. Debussy attended Ansermet’s performance of Satie’s Parade, and he invited Ansermet to his home. He was a reserved, aristocratic nature, a man apart from his surroundings. Very alone, solitary. Very elegant. He was bohemian when young, but no more as the husband of Mrs. Bardac. He was not jealous, but very convinced of himself. He lived only for his music. A sharp sense of humor. He was not a man to collect scores, only playing his own music. Walter Rummel would come to play Bach, Chopin, and Schumann. Debussy mentioned Stravinsky, enthusiastic about Firebird and Petrushka; but he liked the scoring better than the music. He admired, but he had a critical sense. Stravinsky misrepresents Debussy in his last book. Ansermet was conducting in Paris 1928-29 with Forrestier. Mrs. Debussy was very appreciative. Debussy found Nijinsky’s choreography for the Faun too mechanical. Jeux is wonderful, but also Debussy saw its choreography by Nijinsky as too erotic, unsatisfactory. The Beethoven Fourth (28 August 1958) looms large, especially in the first movement Adagio–Allegro vivace, which might adumbrate some dire tragedy. But the Homeric humor bursts forth, and Ansermet takes the repeat as a natural process of exposition, the tympani rolling, the strings rollicking. Lovely flute work from the Philharmonia, the bassoon bubbling underneath in anticipation of the Pastoral Symphony. The second movement Adagio proves more personal in its lyric drama, with lovely interplay from French horn (Alan Civil?) and flute. A bustling, often jabbing Allegro vivace Scherzo fraught with mystery segues to the unbuttoned Allegro ma non troppo, where Zeus might be said to frolic thunderously with whipped cream. – Gary Lemco