Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

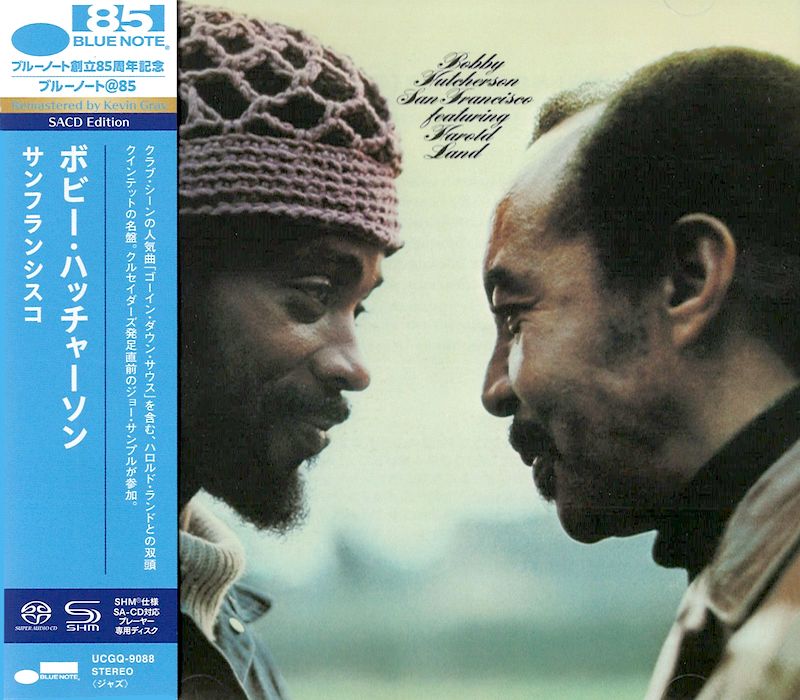

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

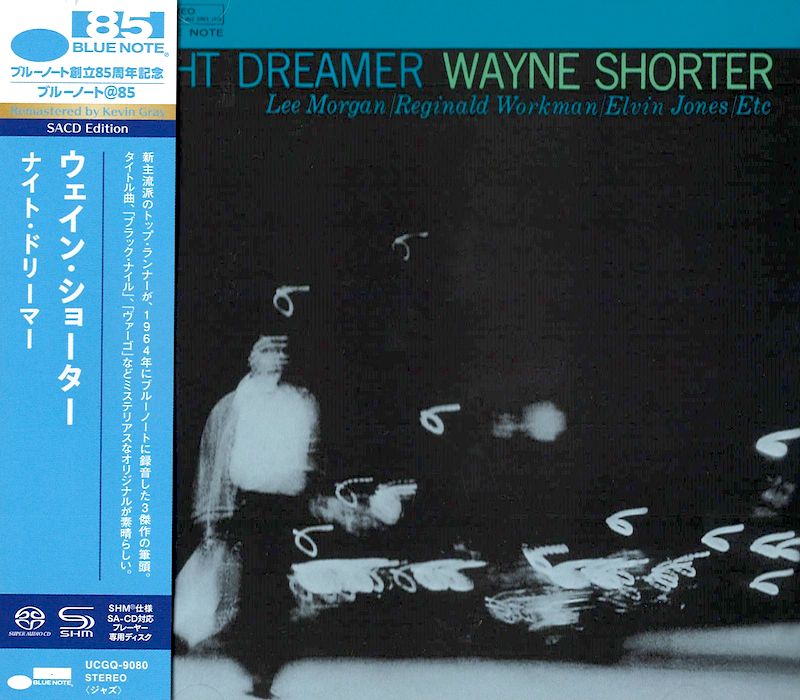

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Karnawał czas zacząć!

Music of Love - Hi-Fi Latin Rhythms

Samba : Music of Celebration

AUDIOPHILE 24BIT RECORDING AND MASTERING

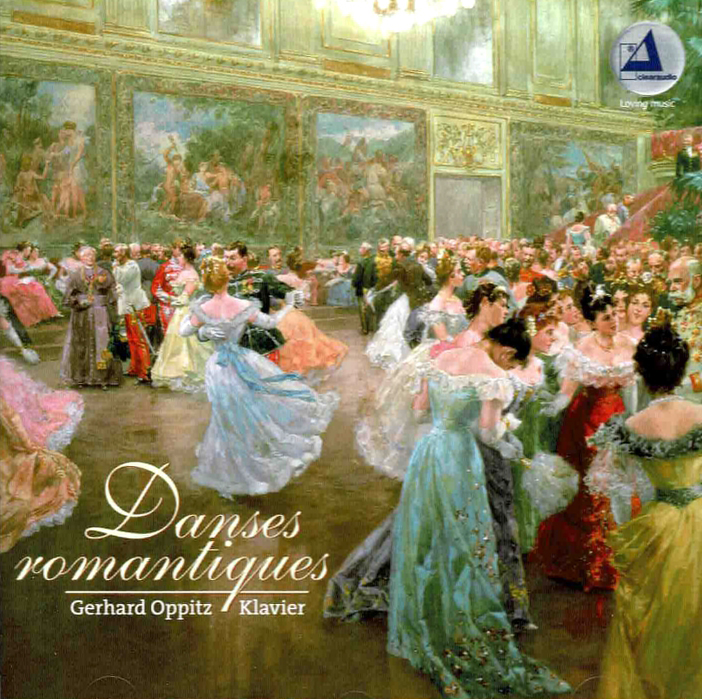

CHOPIN, LISZT, DEBUSSY, DVORAK, Gerhard Oppitz

Dances romantiques - A fantastic Notturno

Wzorcowa jakość audiofilska z Clearaudio

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

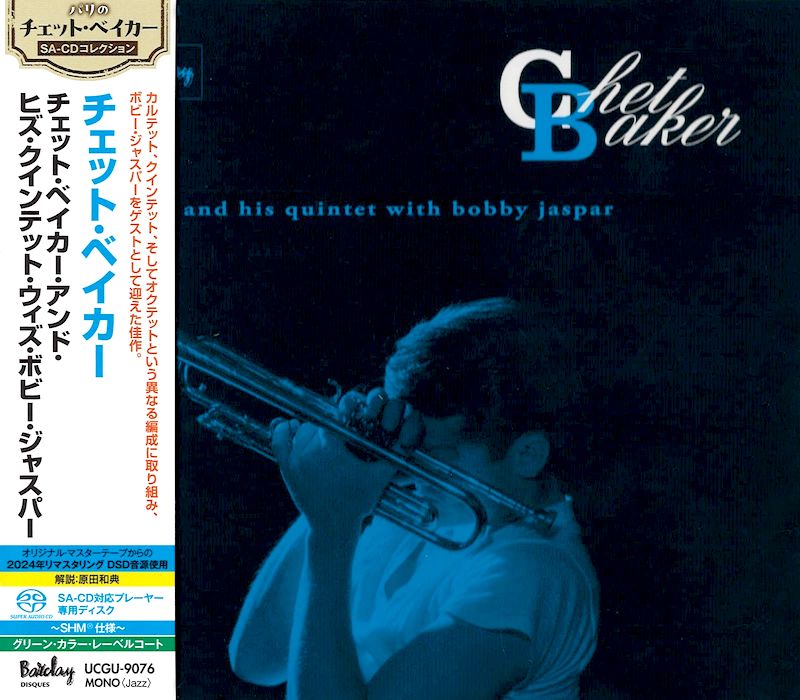

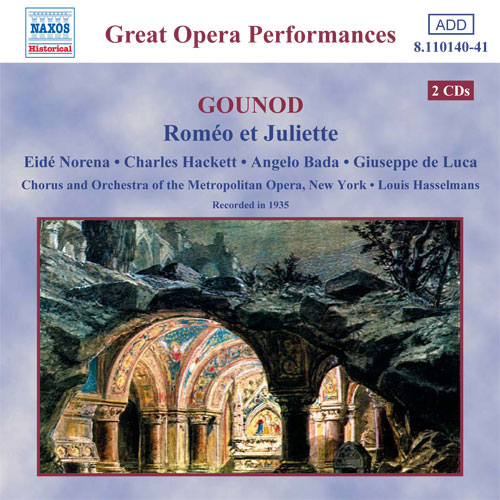

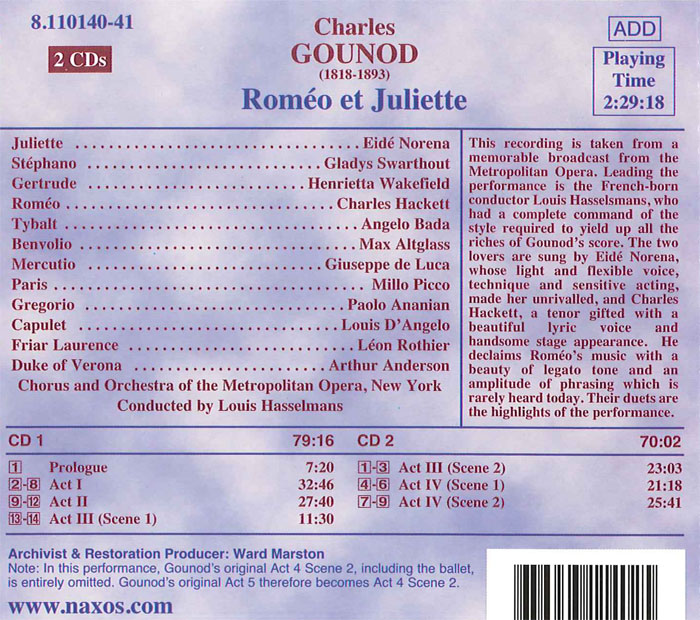

GOUNOD, Eide Norena, Charles Hackett

Romeo et Juliette

Charles GOUNOD (1818-1893) Roméo et Juliette Charles Gounod, one of the great nineteenth-century masters of operatic melody, had a huge early success with Faust, based on the dramatic poem by Goethe, and spent the rest of his career trying to match it. He came closest with a work based on a play by another great poet, Shakespeare. His setting of Roméo et Juliette was composed in 1865-67 with the help of the librettists Jules Barbier and Michel Carré, who had served him well with other operas including Faust. To make Shakespeare’s tragedy suitable for the lyric stage, much of it had to be cut; the result was that the two star-crossed lovers loomed even larger in the opera than they had in the play. Gounod rose to the occasion with a series of marvellous duets for the tenor and soprano who took the title rôles – like other operatic composers who tackled Shakespeare’s text, he could not resist having a final duet in the Tomb Scene, which meant the story had to be adjusted. Otherwise his librettists stuck reasonably closely to the original. The tenor was given much superb declamatory music as well as a magnificent aria; and the soprano was allotted one of the waltz-songs which were de rigeur in French opera at the time. This song, the opera’s only other hit number, unless you count the baritone’s Queen Mab song, was a late addition; Gounod originally intended Juliette’s rôle to be more declamatory like that of Roméo, but found himself with a relatively light soprano, Marie Miolan-Carvalho, for the première. He therefore capitulated to her request for something brilliant in Act I and allowed her to omit her big aria in Act IV Scene 1. Since then Juliette has usually been sung by a lyric soprano and so this aria has generally been cut, as on this recording. The first performance took place in the Théâtre-Lyrique, Paris, on 27th April 1867 and within three months the opera had been heard in London with Patti and Mario. By the end of the year it had been staged in New York and other major centres. Famous exponents of Juliette have included Melba, Farrar, Heldy, Féraldy, Norena, Sayão, Micheau and Freni, while Roméo has been sung by Jean de Reszke, Ansseau, d’Arkor, Crooks, Thill, Luccioni, Björling and Kraus. Roméo et Juliette was not recorded during the 78rpm era, even though many of the singers mentioned above made important individual discs, so we must rely on Saturday-matinée broadcasts from the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where it was a repertoire piece for many years. If we want to hear how it was performed in the heyday of French style, there is only one choice, this broadcast from the l934-35 season. Change was in the air at the Metropolitan, as the long-serving manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza was about to retire, but the structure he had built up, with its fine chorus and orchestra and its excellent supporting singers, was still in place. The cast of our Roméo includes one legendary character singer, the tenor Angelo Bada, who had actually come over from Italy with Gatti-Casazza in 1908, and another, the bass Léon Rothier, who had been at the Met since 1910. One of the protagonists, the illustrious baritone Giuseppe de Luca, had adorned the Met stage since 1915 (his reward for such loyalty was to be disposed of on Gatti’s departure, a decision which deeply upset him, although he returned for the 1940-41 season). The new generation is represented by the mezzo Gladys Swarthout, a dull singer on her studio records but more sprightly when heard ‘live’. What makes this recording special, apart from the still vibrant de Luca and the sonorous Rothier, is the singing of the tenor and soprano and the superbly stylish conducting. Granted, in an ideal world both Eidé Norena and Charles Hackett would be able to ‘retake’ a few notes (better still, they would be recorded at a slightly younger age) but there is enough wonderful singing here to make the pulse beat faster. She characterizes Juliette as a real teenager: her singing is full of wide-eyed wonder and hope until the tragic dénouement. He declaims Roméo’s music with a beauty of legato tone and an amplitude of phrasing which is rarely heard today. Their duets are the highlights of the performance, which is as it should be. In the pit, the masterly Louis Hasselmans knows exactly when to exert control and when to give the singers their heads. Listen to how beautifully he and the orchestra phrase the opening bars of Act II. The big moments are finely handled and the final peroration, though spoilt by the usual crass applause of the Met audience, is magnificent. An incidental pleasure is the commentary of Milton Cross, with his inevitable mention of the afternoon’s sponsor. Louis Hasselmans, born in Paris on 15th July 1878 into a prominent musical family of Belgian extraction, made his mark as a cellist, taking a first prize at the Conservatoire in 1893. He was principal of the Concerts Lamoureux and a member of the celebrated Quatuor Capet before turning to conducting. From 1909 to 1911 he was at the Opéra-Comique, and again in 1919-22, in Montreal in 1911-13 and at the Chicago Civic Opera in 1918-19. He was a close friend and colleague of Gabriel Fauré. In 1913 he conducted the first Paris performance of Pénélope and four years later Fauré dedicated his First Cello Sonata to him. Hasselmans first conducted at the Met on 20th January 1922 (Faust) and stayed for fifteen seasons, giving 378 performances of fourteen French operas including the Met premières of Pelléas et Mélisande, L’heure espagnole and Don Quichotte. He died at San Juan, Puerto Rico, on 27th December 1957. Eidé Norena was born Karolina Hansen at Horten, in Norway, on 26th April 1884, and studied with Ellen Gulbranson in Oslo. Having started as a concert singer in 1904, she made her operatic début in Oslo in 1907. In 1909 she married the actor Egel Naess Eidé and began calling herself Kaja Eidé. She sang mainly in Oslo and Stockholm before undergoing further studies with Raimund von zur Mühlen and belatedly starting an international career as Eidé Norena. Although her début rôle at La Scala (1924), Covent Garden (1924), the Paris Opéra (1925) and Chicago (1926) was Gilda in Rigoletto, she became a byword for style in the Franco-Belgian repertoire – from 1928 she lived in Paris and was a favourite at the Opéra. She had only a few seasons at the Met. She died in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 19th November 1968. Norena made beautiful records of French and Italian repertoire. Gladys Swarthout was born at Deepwater, Missouri, on Christmas Day 1900 and studied in Chicago, where she made her début at the Civic Opera in 1924. Her Met début came on 15th November 1929 as La Cieca in a matinée of La Gioconda and in thirteen seasons she sang 22 rôles. Her good figure made her an asset in travesty rôles and in the 1930s she became a popular film star, renowned as one of America’s best-dressed women. Her most famous stage rôle was Carmen. The last years of her career were affected by heart trouble and in 1954 she retired to Florence, where she died on 7th July 1969 at her villa, La Ragnaia. America, land of baritones, has produced few tenors of quality but Charles Hackett was undoubtedly one of them. Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, on 4th November 1889, he began as a boy alto, studied in Boston and Florence and started his adult career as a lyric tenor, appearing in Pavia (1915) and Genoa (1916-17). In 1917-18 he was in Buenos Aires and he made his Met début in Il barbiere (with de Luca as Figaro) on 31st January 1919, staying until 1921 and returning in 1934 for five more seasons. In between he sang at La Scala and in Monte Carlo, Paris, London (taking part in Melba’s farewell evening, as Roméo to her Juliette in the Balcony Scene) and Chicago. During this time his voice gained a little in power but kept its tone. He retired in 1940 and taught at the Juilliard School but died all too soon in New York on New Year’s Day 1942. He made a number of records, not all featuring material worthy of him. Angelo Bada was born in Novara on 27th May 1876 and died there on 23rd March 1941. His only vocal training was as a boy soprano at the Cathedral. From 1898 he sang the small operatic rôles in which he specialised; by 1905 he was at Covent Garden and by 1906 at La Scala. In 1910, by which time he had begun his thirty-year stint at the Met, he sang at the Paris Opéra. A master of make-up and characterization, he made many guest appearances at other theatres and was Dr Caius in Toscanini’s Falstaff at Salzburg in 1935. He can be heard on a number of studio recordings and broadcasts. Giuseppe de Luca was the all-rounder among the great baritones of the Golden Age, equally effective in comic and tragic rôles. Born in Rome on Christmas Day 1876, he was an excellent boy soprano and sang in a church choir, making his operatic début at ten. His teachers were Bartolini, Persichini and Cotogni. In 1897 he made his adult début in Faust at Piacenza and by 1900 he was at the San Carlos, Lisbon. He sang in the premières of Adriana Lecouvreur, Siberia and – less luckily – Madama Butterfly; the last two of these were at La Scala. From 1905 he sang in South America, from 1906 in Russia and from 1907 in London. His Met début was made on 25th November 1915 as Rossini’s Figaro. In a career lasting more than half a century he sang everywhere with great success, taking part in more premières and making many records. Some of his interpretations of the standard arias are virtually definitive. He can also be heard on a Met broadcast of La Bohème from 1940. Léon Rothier, born in Rheims on 26th December 1874, began his career as an orchestral violinist in his home city before taking up singing seriously and studying at the Paris Conservatoire. He made his début at the Opéra-Comique in 1899 as Jupiter in Gounod’s Philémon et Baucis and the following year took part in the première of Louise. He left the Opéra-Comique in 1907 and sang in various French theatres before starting his thirty years at the Met. As late as 1949 he gave a recital at Town Hall, New York. He died in that city on 6th December 1951. Among his recordings are two scenes from Un ballo in maschera with Caruso. Tully Potter