Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

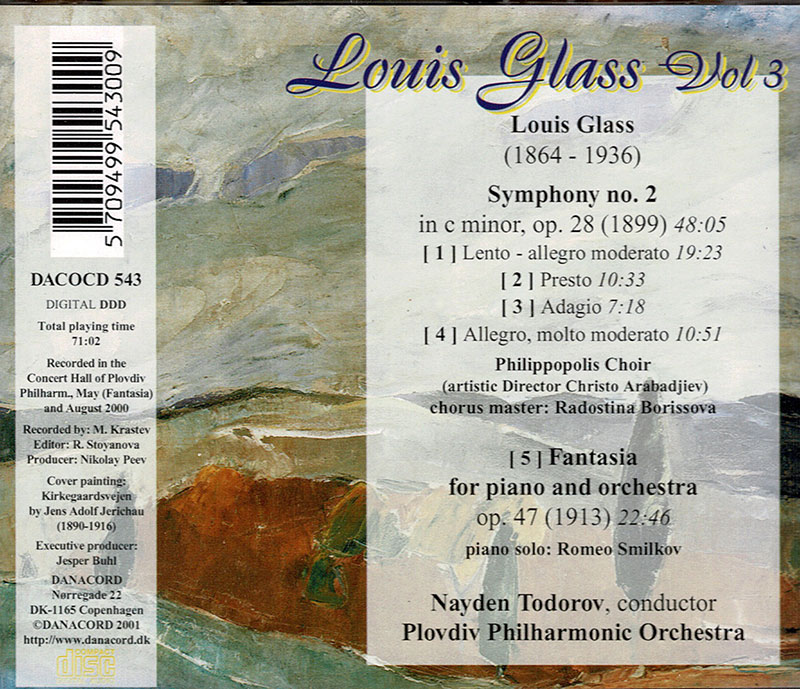

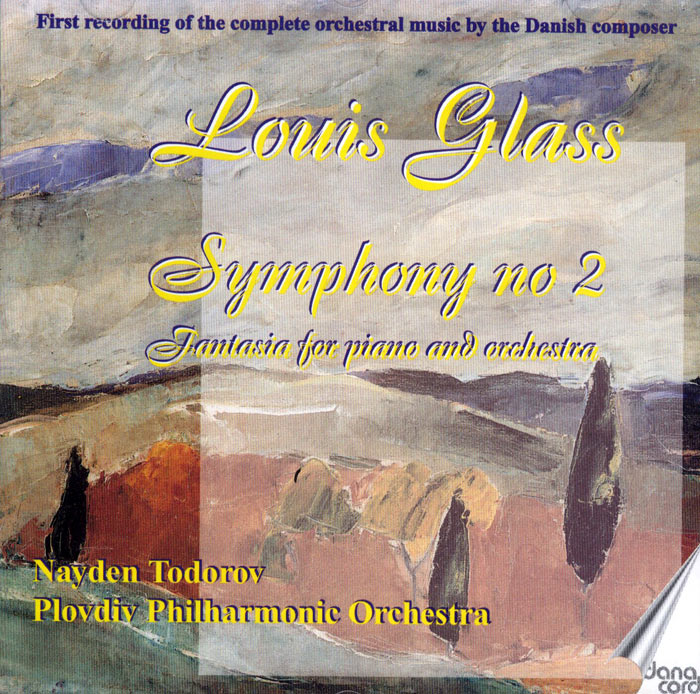

GLASS, Nayden Todorov, Plovdiv Philharmonic Orchestra

Symphony no. 2 - Fantasia for piano and orchestra

- Louis Glass (1864-1936)

- Symphony no. 2, c-minor, op. 28 (1899)

- [ 1 ] Lento - allegro moderato 19:23

- [ 2 ] Presto 10:33

- [ 3 ] Adagio - Sound bites: RealAudio / MP3 7:18

- [ 4 ] Allegro, molto moderato - Sound bites: RealAudio / MP3 10:51

- Fantasy for piano and orchestra, op. 28 (1913) 22:46

- Piano solo: Romeo Smilkov

- Nayden Todorov - conductor

- Plovdiv Philharmonic Orchestra - orchestra

- GLASS

This is volume 3 in Jesper Buhl's Danacord project to record the complete orchestral music of Louis Glass. By our current meagre knowledge Glass's right to fame rests on his Fifth Symphony. The Fifth is a work of memorable lyrical power borne up on waves of ecstatic elation. There is something of Delius in the fully mature music but in its synapses are fused the fluent dynamics of Tchaikovsky. Until we hear Blomstedt, Pappano, Rattle, Salonen and Bostock conducting the Fifth with the world's best orchestras there will still be work to do for Glass. For the current generation the Second Symphony was, until now, a completely unknown quantity. While symphonies 3, 4, 5 and 6 were known to a few from Danish Radio broadcasts, numbers 1 and 2 were passed by and there are no easily accessible comparisons. The Third Symphony had a Brucknerian melos. Bruckner is also, and most assuredly, an influential voice in the Second but so also is the gentler Beethoven and the dramatics of Schumann's Fourth Symphony. The more I hear of this Symphony, especially the presto second movement, the more impressed I am with the calibre of Glass's inventive powers. The adagio has a male voice choir singing, here rather mournfully, of melancholy, grief and the night. The words are by J.P. Jacobsen (a Delius favourite). The movement seems part nocturnal meditation and part funeral march. The finale steps out in the quiet bass developing a sturdy subdued march soon joined by the organ for the first time. This movement rather sags and sprawls and one is left wondering if Glass was struggling to create a convincing ending and not succeeding. The much later Fantasia is the closest Glass came to writing a piano concerto. It is pretty distantly removed from the symphony. Its ticking and rolling piano and orchestral patterns recall Bax's Tintagel and the dripping ostinato of the same composer's Spring Fire. This returns at 10.17 and again at 17.07 playing out through the closing sheaf of pages. The writing for lower woodwind is consonant with Bax's November Woods. There is a wonderfully warming cello solo at 4.43 (at 12.18 and 14.45) whose unhandselled pattern is further elucidated by Smilkov's delicately pearly playing (5.38-7.44). Glass's approach links to the Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov concertos (No. 4) without their devastating panache and dusted over with impressionism (try 14.05 to 16.16). The Symphony is a big work and one in which Glass invested some of the best of his creativity at that age. The first two movements are very strong indeed. The focus blurs in the enigmatic third movement and the finale ambles repetitively. It is still fascinating to meet the symphony at long last. The Fantasy is an elusive and enigmatic piece perhaps closer to two other works for piano and orchestra: Fauré's Ballade and Ireland's Legend. The orchestra, conductor and technicians are in good form perhaps the best so far in this series. Rob Barnett