Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

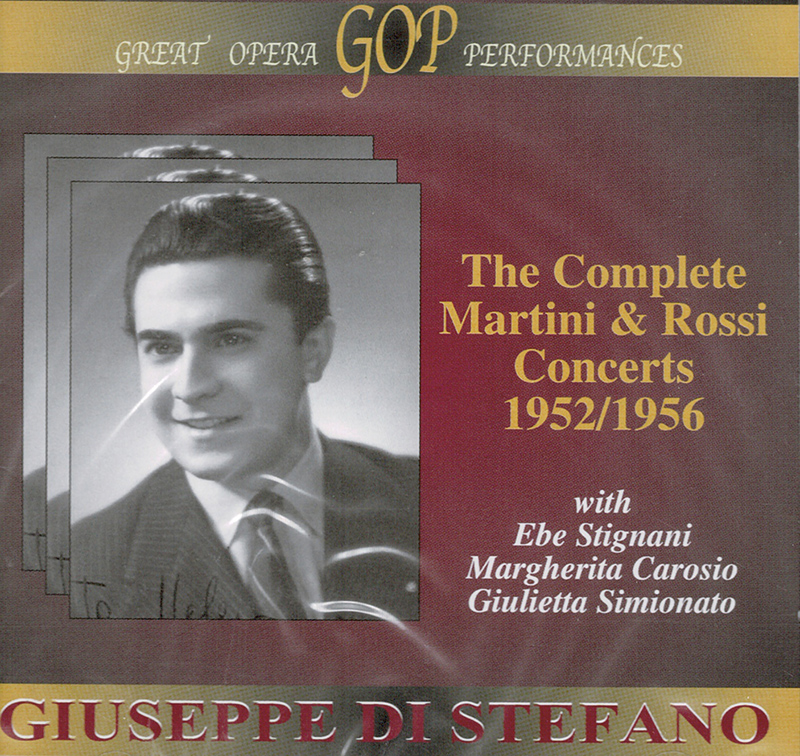

Giuseppe di Stefano

Complete Concerti Martini and Rossi 1952/1956

- Giuseppe di Stefano - tenor

In 1948, Rudolf Bing marvelled at the way Giuseppe Di Stefano treated the diminuendo high C from Gounod's Faust. The artistry with which Di Stefano, then making his Metropolitan debut, resolved the note from forte to the barest of pianissimos was the most beautiful sound Bing had ever heard from a human throat which is wonderful if singing was all about pianissimos. There are many examples of Di Stefano's artistry to enthuse over in this album of Martini and Rossi concerts between 1952 and 1956. He was in his element then and was part of the golden operatic trio that Walter Legge had cultivated from the ravages of post-war Europe. There was Maria Callas, Tito Gobbi and himself. Callas was on the verge of acquiring the legendary status she still enjoys. Gobbi had been a firm favourite with audiences since his debut in 1935 and Di Stefano had been trumpeted as the new Gigli: the voice of the century. By 1964 it all came crashing down. Like a pack of cards lacking proper foundations his beautiful lyric tenor voice started developing flaws that could probably have been avoided. Listening to these recitals is an eye-opener because one can hear how his voice was being produced in a live environment without the benefit of a studio recording where faults can be rectified and problems overcome. He rather naively attributed his vocal problems to an allergy from the rugs he'd installed in his Milan apartment in the mid-1950s. By then he was living a jet-setter's life-style - if jets were prevalent then ... but you know what I mean - and his flawed vocal quality was already affecting his performances. Some experts blame his downfall on a lack of good judgement in singing roles heavier than his lyrical voice could sustain. In fact, most of the arias on this album are no heavier than a lyric tenor would be expected to sing. There are no Des Grieux, Count Almavivas or Ferrandos here. Listening to this album clearly reveals that his 'lyricism' takes a back seat whenever he tries to sustain a note roughly higher that an F above middle C. The voice tightens which indicates he is not using the air in his lungs efficiently. As a consequence sometimes the pitch of the note is not achieved and if this misuse is allowed to continue, long term damage to the vocal mechanism can occur. A good example of this forced projection affecting the pitch of the note is in the second of the Nessun Dormas (on CD2). Here he reaches for the B flat that is the climax of the aria which he can't quite place properly; realising this, he abandons it for a lower note. In a studio recording the aria would have been repeated until an acceptable version had been sung. Which begs the question: why was this allowed to happen? Who knows. What I do feel, however, is that his vocal tutor should have realised there was a problem, taken measures to start developing Di Stefano's lower notes and perhaps have him singing baritone roles. Even as a tenor his middle notes are quite lovely and he could feasibly have become a much sought-after Verdian baritone. This could have extended his artistic life by a few years. What about the rest of this double CD album? Well, I wish I could be more optimistic. There is substantial evidence of what I call 'needle echo' in the transition from what I presume were 78s to digital format. This is especially noticeable when the ladies go for a high note or when the chorus clashes with the soloist and orchestra. The best of the ladies is Giuletta Simionato. Unfortunately Signora Carosio's voice suffers from deficiencies in the recording techniques current at the time. These distorted most treble voices from Melba to Galli-Curci, while Ebe Stignani who retired from the operatic world six years after her appearance in this recital, should have thought about retiring earlier. To give Di Stefano his due I enjoyed his renditions of the Italian canzone/folk-songs probably because there was a noticeable lack of high notes and he was allowed his head in terms of tempi and style. This allowed him to give vent to his obvious passionate nature. His Core 'ngrato alone is almost worth the price of admission. As for being the tenor of the century, I remain to be convinced. Randolph Magri-Overend