Logowanie

TYDZIEŃ z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

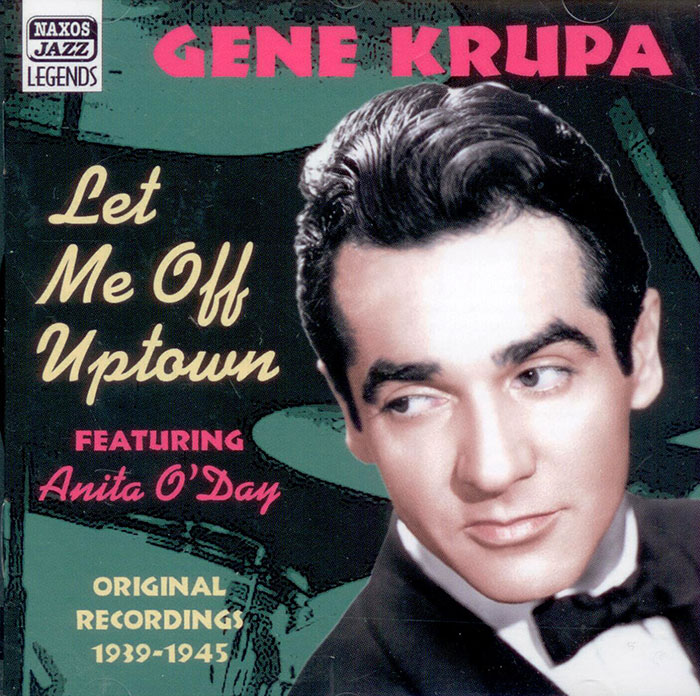

Gene Krupa

Let Me Off Uptown

- Gene Krupa - drums

He may not have been a virtuoso on the level of a Buddy Rich or as swinging a performer as Sid Catlett or Chick Webb, but Gene Krupa was the first drummer to ever become a household name. A superstar and a matinee idol during the Swing era and the decades that followed, Krupa was one of the most colourful and exciting of all drummers. He also led a significant big band during 1938-50. Born 15 January 1909 in Chicago, Gene Krupa was classically trained on drums and throughout his career always took lessons. He first emerged as part of the Chicago jazz scene in 1925, working with the bands of Al Gale, Joe Kayser, Leo Shukin and bassist Thelma Terry in addition to the Benson Orchestra Of Chicago and the Seattle Harmony Kings. In 1927 he made his recording debut with the McKenzie- Condon Chicagoans and immediately made history by being the first musician to use a full drum set on records. After moving to New York in 1929, Krupa worked with Red Nichols’ Five Pennies and became a busy studio musician, playing dance music on radio and records. That lucrative work allowed him to weather the Depression but the music bored him and he longed to play jazz. That opportunity came his way in December 1934 when he was hired to be the drummer with the new Benny Goodman Orchestra. Krupa played with Goodman on the famous Let’s Dance radio series, went on the historic cross country tour that almost ended in disaster a few times and helped launch the swing era at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles when Goodman’s orchestra created a sensation. While Krupa was a relatively quiet drummer with Goodman during 1935-36, by 1937 he was taking drum solos (most notably during “Sing Sing Sing”) and was almost as popular as the King of Swing, being one of the stars of the Benny Goodman Trio and Quartet. After the famous Benny Goodman Carnegie Hall concert of 12 January 1938 during which Krupa was heard at his most assertive, an argument with Goodman resulted in Krupa going out on his own and forming his own big band. At first the Gene Krupa Orchestra did not have much of an individual personality beyond its leader’s drumming, but by 1940 the band had a major singer in Irene Daye and strong soloists in trumpeter Shorty Sherock, trombonist Floyd O’Brien, clarinettist Sam Musiker and tenorsaxophonist Sam Donahue. Feelin’ Fancy starts the set in swinging fashion with the Krupa big band playing a medium-tempo blues with a boogie-woogie feel and solos from pianist Tony d’Amore, Sam Donahue and Shorty Sherock. Manhattan Transfer, which like “Feelin’ Fancy” has an arrangement by Elton Hill, features some catchy riffs that must have delighted dancers of the era. I Like To Recognize The Tune introduces the underrated Irene Daye, a delightful vocalist who later in life became Mrs Charlie Spivak. Tuxedo Junction was a hit for both Erskine Hawkins and Glenn Miller. Gene Krupa’s version is unusual in that it has a spot for his longtime rhythm guitarist Ray Biondi. Irene Daye returns for the spirited How ’Bout That Mess which features her singing some of the more popular slang phrases of the period. She is assisted by tenor-saxophonist Walter Bates, Sherock, Musiker and Krupa. Hamtramck is a hot Elton Hill instrumental with spots for Sherock, Bates, D’Amore and Musiker, all driven by Krupa. Irene Daye’s last session with Krupa ironically resulted in her greatest hit, “Drum Boogie”, which started a series of blues/boogie tunes from Krupa’s band including “Boogie Blues”, “Gene’s Boogie” and “Bop Boogie”. However by the time “Drum Boogie” caught on, Irene Daye had retired to marry trumpeter Corky Cornelius. Daye’s replacement was the most famous new talent ever to emerge from the Gene Krupa Orchestra, Anita O’Day. Just 21 at the time but full of confidence, O’Day was a complete unknown when she recorded her first vocals with Krupa, Alreet and a medium-tempo Georgia On My Mind, but she was already distinctive and a fine jazz singer. It is particularly intriguing hearing O’Day’s version of Drum Boogie, which was originally recorded as a radio transcription. A short time later, the great trumpeter Roy Eldridge, who was at the top of his field, joined the Krupa band. In addition to his explosive solos, Eldridge was a personable singer. Let Me Off Uptown is the Krupa classic of the period, with a memorable melody and lyrics, a swinging vocal by O’Day, clever vocal interplay by O’Day with Eldridge and an exciting trumpet solo. It was the Gene Krupa Orchestra’s biggest hit and made Anita O’Day famous. After You’ve Gone was one of Eldridge’s main features during his year with Krupa. No matter how many times he played this solo, “Little Jazz” always stretched himself and took chances. The Walls Keep Talking has more of O’Day’s singing and Eldridge’s playing. This piece would otherwise be forgotten if it was not for this recording. Krupa’s orchestra was at the height of its success in 1942. The meaning behind O’Day’s mostly wordless vocal on That’s What You Think is mostly open to one’s interpretation. Eldridge’s singing on Knock Me A Kiss works quite well although the hit version of this song was by Louis Jordan. The final number included by this edition of the Krupa big band, Massachussetts, has some jubilant singing by O’Day and a few exciting ensembles. Krupa’s arrest on a charge of possessing marijuana in 1943 (he was framed) resulted in bad publicity, a short jail sentence and the break up of his orchestra. He began his successful comeback in September 1943 when he had a reunion with Benny Goodman. Krupa also played with Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra for a few months in 1944 before forming a new big band. Initially he made the surprising decision of hiring a string section and having his orchestra billed as “the band that swings with strings.” Leave Us Leap was that particular band’s best recording, an Eddie Finckel arrangement that has solos from the boppish trumpeter Don Fagerquist, the rambunctious tenor Charlie Ventura, trombonist Tommy Pedersen, pianist Teddy Napoleon and Krupa. Although the string section was soon dropped, the second Gene Krupa Orchestra lasted over six years. Anita O’Day returned to the orchestra for much of 1945 and her presence helped solidify the band. Her version of Opus No. One, which had previously been a hit for Tommy Dorsey as an instrumental, was a crowd pleaser. Charlie Ventura’s huge tone on tenor and extroverted style are showcased on Yesterdays. Boogie Blues is basically Anita O’Day’s take on “Drum Boogie”; she is assisted by altoist Johnny Bothwell and probably trombonist Pederson along with a rousing final ensemble. This collection closes with an uptempo version of Lover that hints a bit at bebop and features Ventura and Fagerquist. Although remaining a swing drummer, Krupa kept his orchestra open to the influence of bebop during the next few years before its breakup in 1951. During the remainder of his career, Krupa led small groups (usually trios), toured with Jazz At The Philharmonic and had occasional reunions with Benny Goodman. Although he was surpassed on a technical level by many other percussionists, Gene Krupa remained the most famous and beloved drummer up to the time of his death at age 64 on 16 October 1973. Scott Yanow – author of 8 jazz books including Swing, Jazz On Film, Bebop, Trumpet Kings and Jazz On Record 1917-76