Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

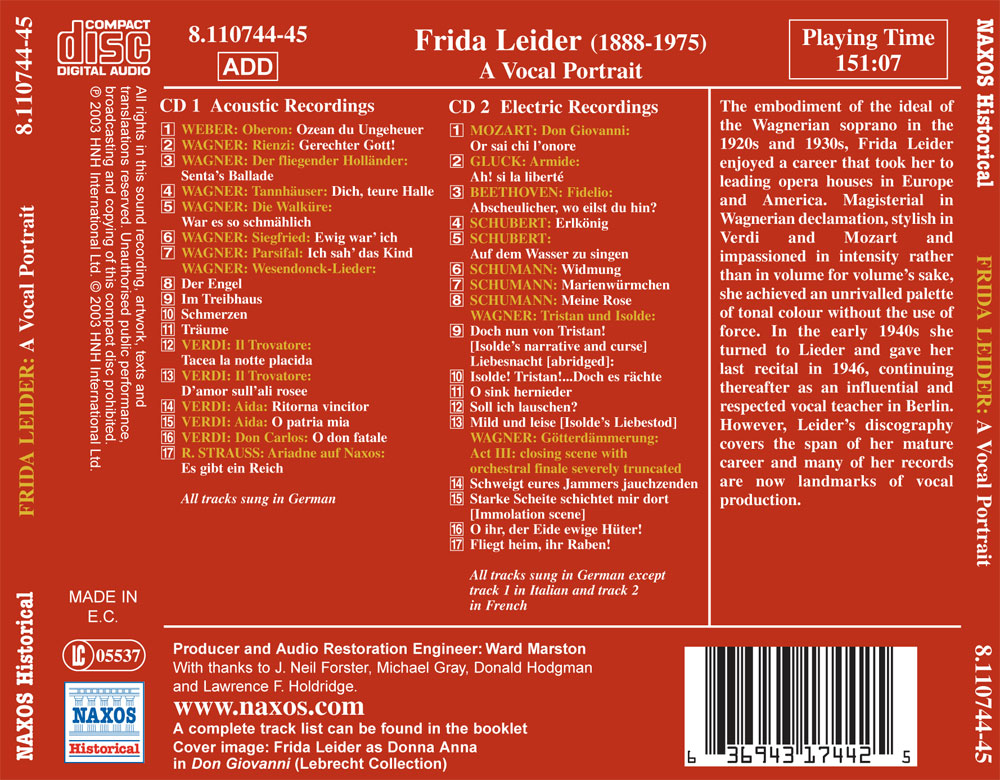

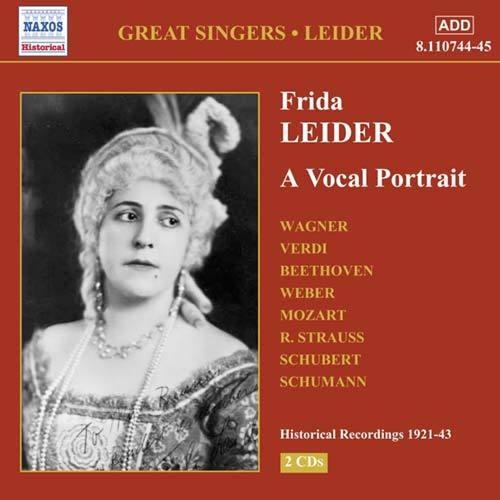

Frida Leider

A Vocal Portrait

- Frida Leider - soprano

Historical Recordings 1921-43

Frida Leider (1888-1975) A Vocal Portrait The soprano who between the wars embodied more than any other the ideal of the Wagnerian dramatic soprano, Frida Leider was born in Berlin on 18th April 1888, the only child of a carpenter and a farmer’s daughter who hailed from Lausitz. Although she received a good education (she attended the Luisenschule, her local high school, originally intending to become a schoolteacher herself) neither of her parents was musical and initially they paid little heed to Frida’s early interest in music. Her youth, however, as she relates in her 1959 memoir Das war mein Teil, translated in 1966 as Playing My Part, "coincided with the full flowering of the Imperial Opera", where her heroines included Geraldine Farrar and Frieda Hempel. At thirteen she saw her first opera, Il trovatore and made singing her ambition, although during her teens her father died prematurely and to earn her living she left school and took a commercial apprenticeship with a bank. At first self-taught in music (she bought a piano to learn repertoire) Frida Leider trained in voice privately, with various teachers, in her spare time. After first auditioning for the Imperial Opera chorus (mercifully, she was turned down as her voice was considered too "dramatic") she studied in Berlin with, among others, Otto Schwartz and made her entry into opera not par la grande porte but via the more provincial route of Halle where, in the comprimario rôle of Venus in Tannhäuser, she made her début at the Stadttheater, in 1915. The following year she sang her first Walküre Brünnhilde, under Robert Heger, at Nuremberg and from then until 1919 was contracted to Rostock Opera. In 1920 she sang briefly in Königsberg before moving to Hamburg where her career really took off. There she won acclaim not only in Wagner but in a range of other rôles, Mozartian and Verdian, all in German translation, including Donna Anna in Don Giovanni, the Countess in Figaro, Aïda and Amelia in Ballo in maschera, and was also heard as Ariadne and in the rather less congenial castings of Tosca and Santuzza. By 1923 Leider had graduated to the Berlin Staatsoper (her début was as Fidelio, under Erich Kleiber) which became her artistic and spiritual home until 1940, although her guest appearances in the world’s leading opera-houses were numerous and regular. In 1924 she made her début at Covent Garden and would remain an adored favourite with London audiences, undisplaced by Flagstad and other notable rivals, until 1938, when she made a last appearance in Götterdämmerung, under Furtwängler. At Covent Garden she appeared in international Grand Opera and Wagner Festival seasons, including Ring cycles and eight Isoldes, and in a variety of other rôles, including a "dignified and wistful" Marschallin in Rosenkavalier, Donna Anna, Leonora in Il trovatore, Gluck’s Armide and Kundry in Parsifal. At La Scala, Milan, under Ettore Panizza, in 1927, she sang Brünnhilde in Walküre and Götterdämmerung and the following year returned for all three Brünnhildes. Again rapturously received, she was offered Isolde and other rôles and might easily have taken up residency in Italy if other offers pouring in all at once from London, Bayreuth and South America had not prompted her to send "a refusal to Milan, thereby renouncing an Italian career." During 1928 Leider sang Brünnhilde and Kundry at Bayreuth (she would make further guest appearances at the Festival in 1933 and 1938) and the first of four consecutive guest seasons at the Chicago Lyric Opera, followed by tours of the States. Between 1930 and 1932 she made various appearances at the Paris Opéra, in 1931 participating in the German Zoppot Festivals and singing for the first time at the Colón in Buenos Aires. During the 1933-1934 season she made a somewhat delayed, if much heralded début at the New York Metropolitan. Her reputation as the greatest Isolde of her day had preceded her and the New York Daily Tribune, while praising her voice for its "singular beauty and expressiveness" and the " rare loveliness and purity" of its middle register, lauded her portrayal for "the sovereign dignity…elect intensity…passion that remains patrician…enlarging tenderness…richness of feeling"…and "poetry of the imagination that set it apart from the Isoldes of our time." By all accounts, however, neither New York’s climate nor the fees on offer (since the 1929 Wall Street crash singers at New York’s premier theatre had been obliged to accept cuts in salary) were really to Leider’s liking, and after only two seasons she left, her departure opening the Met’s door to the then unknown Kirsten Flagstad. The advent of the Nazis in Germany, furthermore, made travel to the United States a virtual impossibility and her career in opera had virtually ground to a halt by 1940, when her violinist husband Rudolf Deman, the leader of the Berlin Staatsoper Orchestra and a Jew, was forced to take up permanent residence in Switzerland. Leider, however, refusing to countenance permanent separation from him, contrived, through a partnership with pianist Michael Raucheisen, a second career as a recitalist which involved regular concerts on the Swiss circuit. At the end of the Second World War Leider lived with her mother on the outskirts of Berlin, where she gave her last recital on 16th February, 1946. Seeking solace afterwards in teaching, from 1945 until 1952 she ran a vocal studio attached to the Berlin Staatsoper and from 1948 until 1958 was a highly respected professor of singing at the Berlin Musikhochschule. Leider’s comparatively small discography covers the span of her mature career and many of her records are now landmarks of vocal production, if not perhaps always of interpretation, in the sense that the term is so often misapplied today. In even the earliest we hear a lyric-dramatic soprano of substantial proportions: magisterial in Wagnerian declamation, stylish in Verdi and Mozart, impassioned in intensity rather than in volume for volume’s sake, the voice of one who is thoroughly sure of her trade. In common with others of her generation, the majestic quality of Leider’s singing (a quality audibly absent among modern sopranos) was the product of a correct vocal education combined with exposure to good models. She achieves a palette of tonal colour and an unrivalled expressiveness without forcing and her remarkable evenness of production creates an overall impression of strength and tenderness, of light and shade interwoven. Even the very first, of Reiza’s apostrophising of the sea as a "Mighty Monster" from Weber’s Oberon, offers a fine illustration of the easy legato of her warm and captivating middle register with its powerfully mellifluous, mezzo-like quality (her voice was originally, if erroneously, thus categorised). In the finale, "Hüon!, Hüon!", she makes staggeringly light work of the aria’s demands for dramatic coloratura in the upper register. Frida Leider died in Berlin on 4th June 1975. Peter Dempsey Ward Marston In 1997 Ward Marston was nominated for the Best Historical Album Grammy Award for his production work on BMG’s Fritz Kreisler collection. According to the Chicago Tribune, Marston’s name is ‘synonymous with tender loving care to collectors of historical CDs’. Opera News calls his work ‘revelatory’, and Fanfare deems him ‘miraculous’. In 1996 Ward Marston received the Gramophone award for Historical Vocal Recording of the Year, honouring his production and engineering work on Romophone’s complete recordings of Lucrezia Bori. He also served as re-recording engineer for the Franklin Mint’s Arturo Toscanini issue and BMG’s Sergey Rachmaninov recordings, both winners of the Best Historical Album Grammy. Born blind in 1952, Ward Marston has amassed tens of thousands of opera classical records over the past four decades. Following a stint in radio while a student at Williams College, he became well-known as a reissue producer in 1979, when he restored the earliest known stereo recording made by the Bell Telephone Laboratories in 1932. In the past, Ward Marston has produced records for a number of major and specialist record companies. Now he is bringing his distinctive sonic vision to bear on works released on the Naxos Historical label. Ultimately his goal is to make the music he remasters sound as natural as possible and true to life by ‘lifting the voices’ off his old 78 rpm recordings. His aim is to promote the importance of preserving old recordings and make available the works of great musicians who need to be heard.