Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

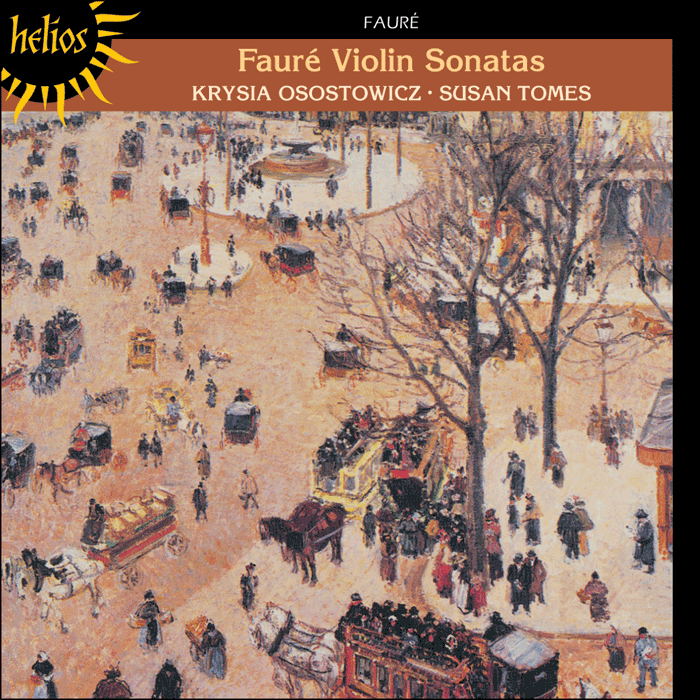

FAURE, Krysia Osostowicz, Susan Tomes

Violin Sonatas

- Krysia Osostowicz - violin

- Susan Tomes - piano

- FAURE

Few composers have lived through such far-reaching changes in musical climate as Fauré. When he composed his first works, in the 1860s, French musical life was dominated by Gounod and Mendelssohn, and the grandiose operas of Spontini and Meyerbeer. Chopin, Liszt and Wagner were still considered daringly modern in most circles. By the time of his death in 1924, Debussy had been dead for six years, Berg had completed Wozzeck, and Schoenberg had formulated his twelve-tone system. Yet, although a considerable gulf does exist between Fauré’s early works and his music of the 1920s, he remained largely impervious to outside influences after he had evolved a distinctive personal style. His development from the First Violin Sonata and First Piano Quartet, both dating from the mid-1870s, to the chamber music and songs of his last ten years, was gradual and self-consistent. His harmonic language, based on a highly original fusion of tonality and the ancient church modes, grew more subtle and ambivalent. His textures became at once more lucid and more dense contrapuntally, his rhythms and melodies more flexible, and his forms both freer and more economical. But at no point in Fauré’s career was there any fundamental change in compositional technique. Despite its more complex harmonic language and its more elusive emotional character, the Second Violin Sonata, completed in 1917, is self-evidently the work of the same composer as the First Sonata written more than four decades previously. In the mid-1870s Fauré was still relatively unknown and earning his living as a teacher at the Ecole Niedermeyer in Paris (where he had been a student), and as assistant organist at St Sulpice and La Madeleine. But, partly through the influence of Saint-Saëns, he was just beginning to make his way in Parisian society: he became a regular guest at the soirées given by the great Spanish contralto Pauline Viardot, and was befriended by the family of the wealthy, music-loving industrialist Camille Clerc. It was at the Clercs’ summer residence at Sainte-Adresse on the Normandy coast that Fauré embarked on the A major violin sonata in the summer of 1875. He was evidently inspired by the presence of the talented Belgian violinist Hubert Léonard, who would try out the music as it was being composed. The work was completed early the following year, but was immediately rejected by Parisian music publishers alarmed by its originality and harmonic audacity. Only through the efforts of Camille Clerc did the sonata find its way to Breitkopf und Härtel in Leipzig, who published it in 1877. Violin Sonata No 1 in A major, Op 13, was enthusiastically received at its first performance in January 1877, and prompted a glowing review by Saint-Saëns in the Journal de Musique. Today it remains arguably the most popular of all Fauré’s chamber works, cherished for its freshness and verve, its characteristic Fauréan balance of elegant restraint and romantic ardour. Though all four movements are constructed along traditional lines (the first, second and last in sonata form), the music is confidently and profoundly individual, quite unlike any chamber music that had been heard before. Fauré proclaims his originality at the very outset: a supple, wide-arching cantilena, at once leisurely and urgent, unfolds over an exceptionally long span of 21 bars. There are already hints of a harmonic restlessness that is intensified in the expressively falling second main theme, sounded on the violin, which modulates ceaselessly over a rising chromatic bass. The development, which casts searching new light on each of the themes in turn, culminates in a particularly beautiful lull, the second theme floating ethereally above deep, hushed piano chords. In the D minor Andante, in 9/8 time, there is a disquieting marriage between the gently swaying barcarolle rhythms often favoured by Fauré, and the intense, at times visionary, chromaticism. The rising piano arpeggios of the opening are inverted in the second idea which begins in a tenderly assuaging F major but is quickly deflected through a passionate sequence of modulations: in the recapitulation this theme, now in D major, builds to a still more searing climax, with astonishingly sonorous scoring. Despite faint echoes of Mendelssohn, the Allegro vivo scherzo is a movement of delicious individuality, with its gossamer textures (note, for instance, the violin’s sudden bursts of pizzicato), its fleet harmonic sideslips and its teasing cross-rhythms. The trio offers a telling change of mood and sonority: a wistful cantabile melody, slightly Schumannesque in feeling, unfolds unhurriedly over a calmly undulating keyboard accompaniment. Not surprisingly, this movement was vociferously encored at its first performance. The 6/8 finale, Allegro quasi presto, draws a striking contrast between its serene opening idea, oscillating hypnotically around a recurrent C sharp (a favourite melodic trait of Fauré) and the bitingly syncopated second theme which, with its various counter-melodies, dominates the closing stages of the exposition. In the development, the first three notes of the initial theme are worked almost obsessively against a new, sinuous violin melody that subtly emphasizes the intervals of the second and third on which the opening idea is built. The coda allows the violin its only flight of pure virtuosity in the work; yet, characteristically, the brilliant spiccato scales are held down to pianissimo until the very last bars. More than forty years separate the A major sonata from its successor, the Violin Sonata No 2 in E minor, Op 108, which initiates the wonderful sequence of Fauré’s late chamber works composed, like the final quartets of Beethoven, under the painful affliction of deafness. The E minor sonata was begun at Evian, on the shores of Lake Geneva, in August 1916 and completed in Paris the following winter. It is a powerful, concentrated work whose first movement attains a violence of expression that reflects both the grim period in which it was composed and, more specifically, Fauré’s anxieties about his son, Philippe, who was away on active service. With its disconcerting shifts of mood, its density of thought and its esoteric harmonic idiom, the E minor sonata found far less favour with the public than its more approachable predecessor. In 1922, when Alfred Cortot was to play the work before Elizabeth, Queen of the Belgians, to whom it is dedicated, Fauré complained to his wife that ‘my poor sonata is still so rarely played’. Even today, when many musicians regard it as the finer of the two violin sonatas, it is still much less well known than the A major. In the first movement Fauré creates music of disturbing force within a design that represents an original interpretation of sonata form. There are three main ideas: the first menacing and syncopated, flaring up from the depths of the keyboard; the second passionate and tortuously chromatic, sounded high on the violin; and the third a gently lyrical melody whose consolatory calm is threatened by the opening syncopated figure in the bass. The sequence of these three ideas, and a broad tonal scheme that moves from E minor to G major, corresponds to a sonata exposition. But what follows is not the traditional development and recapitulation but rather three continuous sections each of which states and develops the themes in their original order. Of these the first can be viewed as a second exposition, the latter two as varied recapitulations. The music touches an intensity of violence at the start of the first recapitulation—where the canonic writing, so characteristic of late Fauré, possesses an almost brutal rawness—and in the coda, which contorts the opening theme into new, harshly angular shapes. The Andante, in A major, exudes the rarified serenity tinged with disquiet that pervades much of Fauré’s later music. Its main theme, derived from the rejected D minor symphony of 1884, sets a melodic line of delicate, refined simplicity against ambivalent chromatic harmonies: on the theme’s reprise, in C major, midway through the movement, the harmonies become still stranger. A second melody, announced espressivo on the violin, hovers hauntingly between E major and the remoteness of F minor; its subsequent developments, often in canon, attain a moving intensity, impassioned yet restrained. The profoundly tranquil coda, with the violin in its deepest register, subtly combines aspects of each of the two main ideas. The opening melody of the E major finale is quintessential late Fauré in its insouciant grace, its unemphatic syncopations and its calmly repeated rhythmic patterns over a strongly defined bass. Two further ideas alternate with this melody in a rondo-like design: a broad, warmly expressive violin theme characterized by its initial falling octave, and a more reserved cantabile melody underpinned by elusive chromatic harmonies. Yet these secondary ideas always glide nonchalantly back to the opening refrain whose hushed appearance, with note-values doubled, at the centre of the movement reveal its kinship with the broad violin tune. Towards the close, Fauré introduces, deep in the bass, the sonata’s opening motif, a reminder of the work’s sombre origins. This then yields to an expanded version of the calm, lyrical idea from the first movement, which now rises to an ecstatic fervour. It is characteristic of Fauré’s whole art that these cyclic references are managed with supreme ease and naturalness, the first emerging as part of a logical growth in the music’s intensity, the second passing in a seamless texture to the rondo refrain and the radiant peroration. Richard Wigmore © 1999