Logowanie

TYDZIEŃ z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

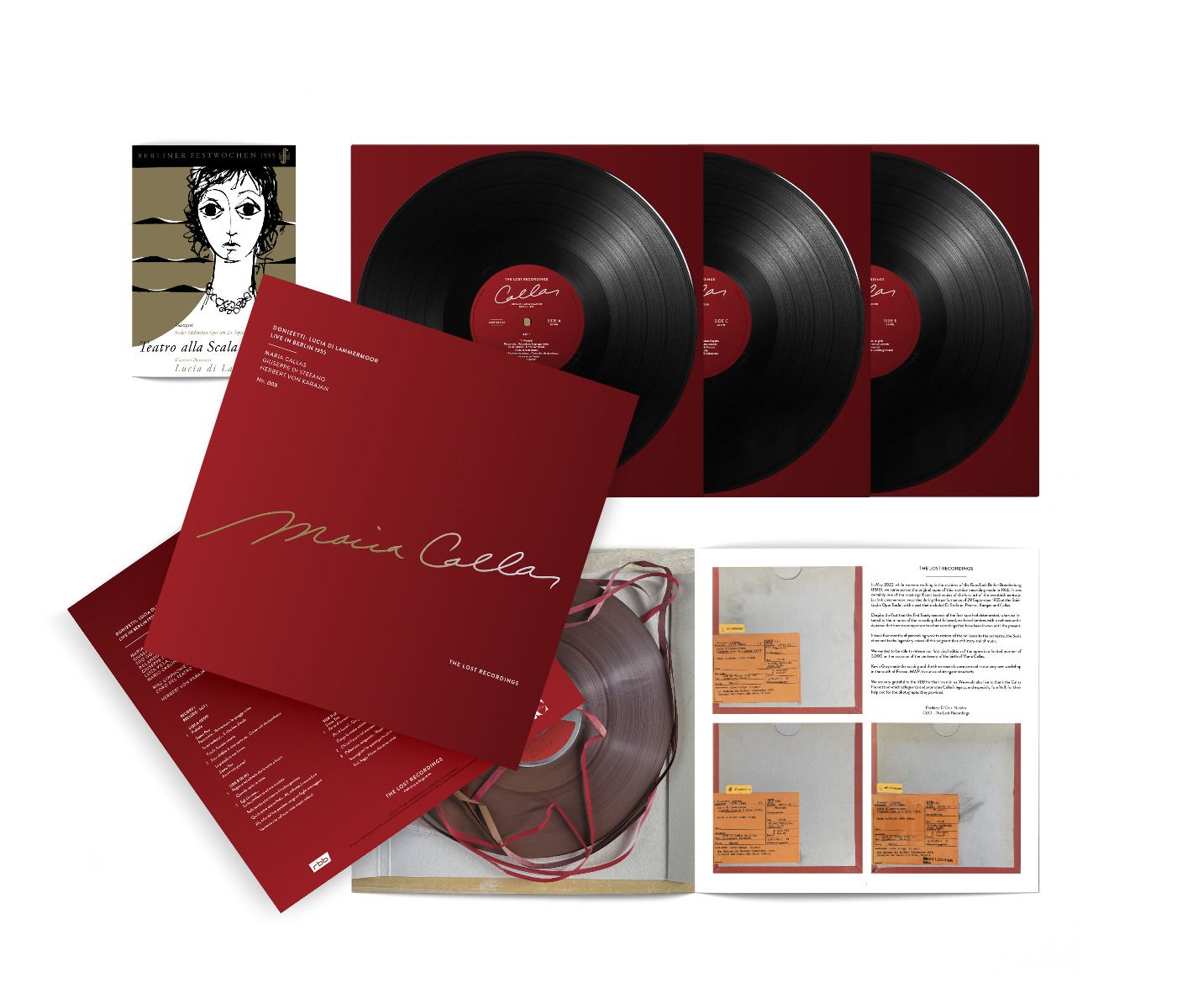

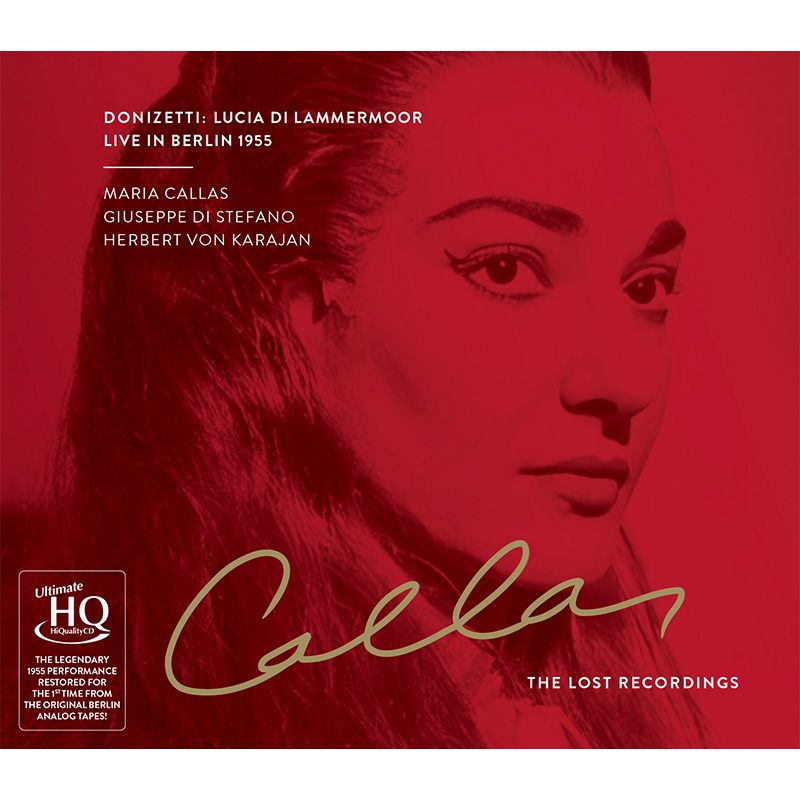

DONIZETTI, Maria Callas, Giuseppe di Stefano, Herbert von Karajan

Lucia di Lammermoor

- Maria Callas - soprano

- Giuseppe di Stefano - tenor

- Herbert von Karajan - conductor

- DONIZETTI

In May 2022, while we were working in the archives of the Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg (RBB), we came across the original tapes of this mythical recording made in 1955. It was certainly one of the most significant testimonies of the lyric art of the twentieth century: Lucia di Lammermoor, recorded during the performance of 29 September 1955 at the Städtische Oper Berlin, with a cast that included Di Stefano, Panerai, Karajan and Callas.

Despite the fact that the first forty seconds of the first tape had deteriorated, when we listened to the minutes of the recording that followed, we heard timbres with a richness and a dynamic that bore no comparison to other recordings that have been known until the present.

It took four months of painstaking work to restore all the brilliance to the orchestra, to the Scala choir and to the legendary voices of this poignant slice of history and of music.

We wanted to be able to release our first vinyl edition of the opera in a limited number of 5,000 on the occasion of the centenary of the birth of Maria Callas.

Kevin Gray made the cutting and the three records were pressed in our very own workshop in the south of France, MWP, to our usual stringent standards.

We are very grateful to the RBB for their trust in us. We would also like to thank the Callas Foundation, which safeguards and promotes Callas’s legacy, and especially Tom Volf, for their help, as well as for the photographs they provided.

Frédéric D'Oria-Nicolas

Founder and Director of The Lost Recordings

I have a very personal connection with Callas’s Lucia, for it is the first recording I heard of hers, more precisely the mad scene; hearing Callas’s voice and interpretation was like falling in love at first sight. This live recording is a wonderful example of what it felt like to hear Callas on stage, in a performance that became legendary.

Maria Callas said she “hated” recording for commercial (studio) releases and used to say that only live performances could convey her artistry in its full spectrum. In the later years of her life, she would collect her own pirate recordings and would often listen to performances such as this one. The best account of that comes from Robert Sutherland, her pianist during the last tour of concerts in 1973-74, who recalled the evenings spent at Callas’s apartment at Avenue Georges Mandel:

“We listened to a pirate recording of the Berlin Lucia. She remembered how Karajan angered the soloists by repeating the sextet without warning them. As we listened to the encore she said ‘You can hear how angry I was! And I still had the mad scene to sing! I told him afterwards at dinner that he dare not do that again on me or there would be trouble!’ We listened to the mad scene, an amazing performance. She was visibly impressed. ‘I don’t now how I did it. I just don’t know how - and to think that I wept after that performance because I thought I was so far off my aim.’ I had difficulty in expressing my reaction. Such a combination of controlled technical brilliance and artistic imagination was astounding. I attempted it with, ‘It’s marvellous singing…’ ‘Marvellous? Marvellous?’ She pulled herself up in the sofa. ‘It isn’t marvellous, it’s bloody miraculous!’”

Back at that time, pirate recordings circulated among avid admirers in the form of homemade LP’s, such as those released by the BJR label which is probably the one that Callas was listening to that night with Robert Sutherland. Today, however, we have to commend Frédéric D’Oria-Nicolas and The Lost Recordings for retrieving the original tapes in Berlin and meticulously restoring them to a quality of sound which surpasses any previous release, thus providing us with the most authentic rendition of that historical performance. Therefore it was only natural for the Callas Foundation to be associated with this publication, providing texts and images to illustrate the booklet and honour the memory of Maria Callas through this magnificent edition celebrating her 100th anniversary.

Tom Volf

President of the Maria Callas Foundation

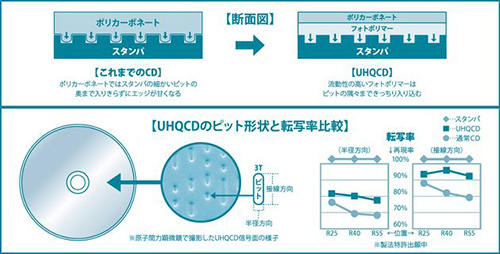

Inżynierom z Japonii i Hong Kongu udało się złagodzić załamanie przebiegu cyfrowego, zbliżając się o kilka procent do wzorca pozbawionego wszelkich zniekształceń.

Moim jednak zdaniem ciekawszy jest technologiczny aspekt tej nowinki – sam krążek CD, a raczej sposób położenia na nim warstwy nośnej dla lasera i jej zabezpieczenie. Zrezygnowano z dotychczas powszechnie stosowanego poliwęglanu na rzecz fotopolimerów. Pozwalają one na bardziej precyzyjne wykonywanie zagłębień (pit) i wypukłości (land). A to warunek niezbędny do odwzorowania na płycie brzmienia jeszcze bardziej zbliżonego do walorów oryginału.

Płyta UHQCD wymaga ze strony melomana nieco większej troski. Należy m.in. unikać bezpośredniego i długotrwałego naświetlania jej promieniami słonecznymi. Warstwa informacyjna została maksymalnie pozbawiona kolorowych obrazków, krzyczących haseł i grafiki. Wszystko w celu zapewnienia laserowi idealnych warunków do odczytu warstwy nośnej.

I to słychać!

Pierwsze płyty w tym formacie to rzeczywiście brzmieniowe klejnoty. Obok Carmen Fantasie – jedno z najbardziej referencyjnych nagrań w dziejach fonografii – kilka krążków zaskakujących przejrzystością sceny ale przede wszystkim najbardziej poszukiwanym aspektem – naturalnością brzmienia.

To takie szklanki, które mimo ciągłego lania do nich wody, nigdy się nią nie napełnią do końca.

Inżynierom z Japonii i Hong Kongu udało się złagodzić załamanie przebiegu cyfrowego, zbliżając się o kilka procent do wzorca pozbawionego wszelkich zniekształceń.

Moim jednak zdaniem ciekawszy jest technologiczny aspekt tej nowinki – sam krążek CD, a raczej sposób położenia na nim warstwy nośnej dla lasera i jej zabezpieczenie. Zrezygnowano z dotychczas powszechnie stosowanego poliwęglanu na rzecz fotopolimerów. Pozwalają one na bardziej precyzyjne wykonywanie zagłębień (pit) i wypukłości (land). A to warunek niezbędny do odwzorowania na płycie brzmienia jeszcze bardziej zbliżonego do walorów oryginału.

Płyta UHQCD wymaga ze strony melomana nieco większej troski. Należy m.in. unikać bezpośredniego i długotrwałego naświetlania jej promieniami słonecznymi. Warstwa informacyjna została maksymalnie pozbawiona kolorowych obrazków, krzyczących haseł i grafiki. Wszystko w celu zapewnienia laserowi idealnych warunków do odczytu warstwy nośnej.

I to słychać!

Pierwsze płyty w tym formacie to rzeczywiście brzmieniowe klejnoty. Obok Carmen Fantasie – jedno z najbardziej referencyjnych nagrań w dziejach fonografii – kilka krążków zaskakujących przejrzystością sceny ale przede wszystkim najbardziej poszukiwanym aspektem – naturalnością brzmienia.

To takie szklanki, które mimo ciągłego lania do nich wody, nigdy się nią nie napełnią do końca.