Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

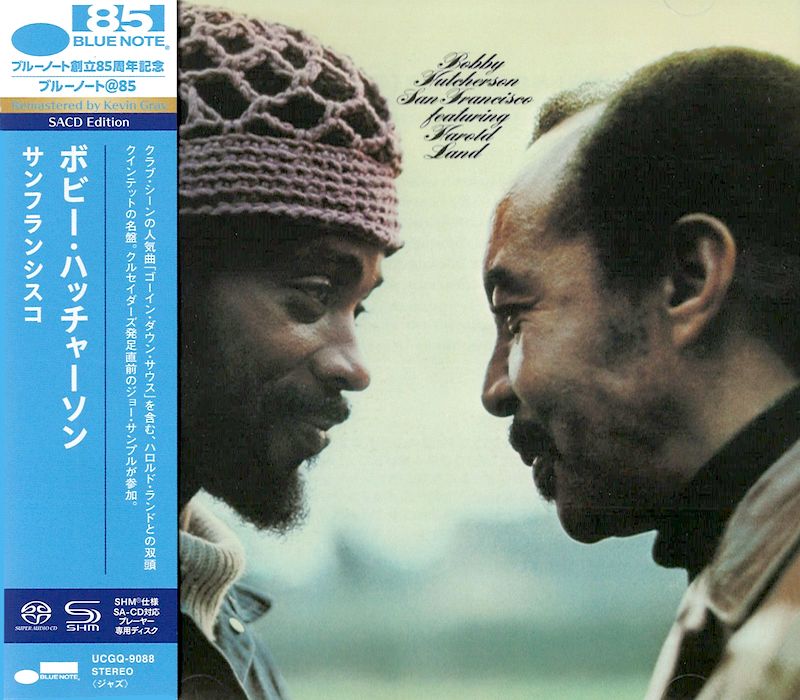

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

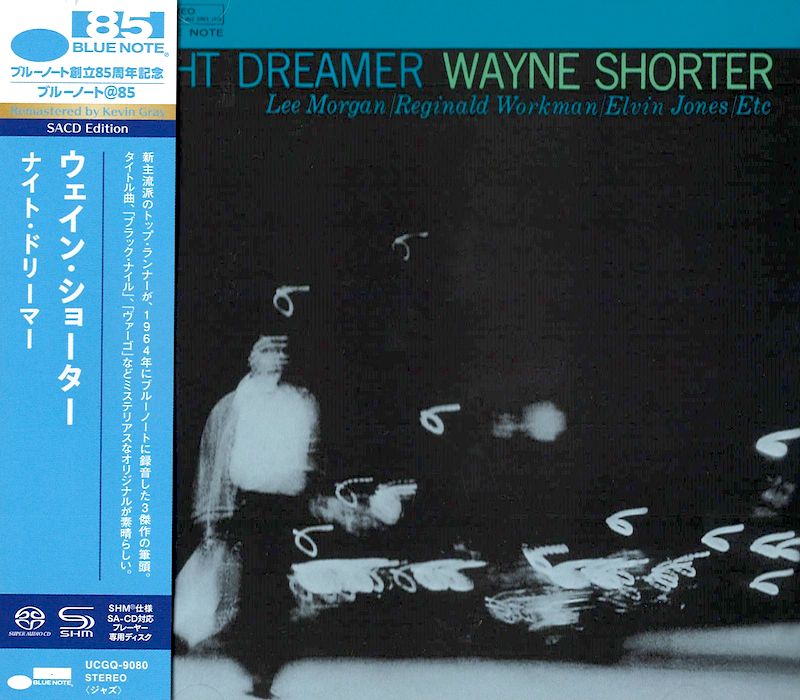

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

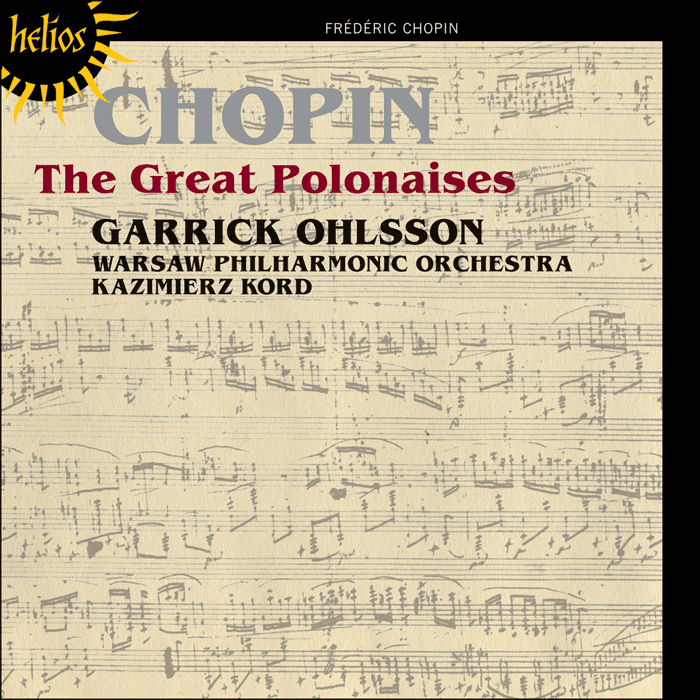

CHOPIN, Garrick Ohlsson

The Great Polonaises

- Polonaise No. 1 in C sharp minor Op. 26 No. 1

- Polonaise No. 2 in E flat minor Op. 26 No. 2

- Polonaise No. 3 in A major Op. 40 No. 1 'Military'

- Polonaise No. 4 in C minor Op. 40 No. 2

- Polonaise No. 5 in F sharp minor Op. 44

- Polonaise No. 6 in A flat major, Op. 53 'Héroïque'

- Polonaise No. 7 in A flat major, Op. 61 'Polonaise-fantaisie'

- Andante spianato & Grande Polonaise, Op. 22

- Garrick Ohlsson - piano

- CHOPIN

By the time of Chopin’s youth, the polonaise had progressed from a Polish dance of rural popularity to the ballrooms of the aristocracy, and he would have heard many of the countless polonaises turned out by Polish composers when he was growing up. There are examples in classical music as far back as Bach, to say nothing of Beethoven, Schubert, Weber and Hummel. But, though the characteristic rhythm of the dance was used well before Chopin, the polonaise is one of the many musical forms where Chopin raised an existing type of composition to another musical level, in this case providing models for Liszt, Scharwenka and later generations. The works presented here are his mature essays in the genre. The two polonaises in C sharp minor and E flat minor, Op 26 composed in 1836 are of a completely different order to the nine polonaises written in his teens and not published till after his death. Not only are they written with a new-found maturity but reflect his situation as a Polish exile in Paris. These polonaises are not virtuosic treatments of a dance form but are by turns proud celebrations of his country’s past splendours and moving expressions of regret at its fate under the Russian oppressors. The trio of the C sharp minor Polonaise could almost stand by itself as a nocturne, the second part of which is a duet between soprano and bass, the prototype of the Étude in C sharp minor, Op 25 No 7. The E flat minor Polonaise is known as the ‘Siberian’ or ‘Revolt’. Its sinister opening section gives way to a reflective trio in B major but ends, in the words of James Huneker, ‘in gloom and the impotent clanging of chains’. The first of the two polonaises Op 40, in A major, the so-called ‘Military’ Polonaise, is one of Chopin’s most popular works. It is, perhaps, the most typical example of his six mature polonaises in terms of its structure, rhythm and character. Here is the composer at his most patriotic yet it is strange that so heroic a work has no coda but simply restates the opening theme before coming to an abrupt conclusion. If this is a portrait of Poland’s greatness, then Op 40 No 2 in C minor, composed a year later in 1839, depicts its suffering in music of nobility and high emotion. The Op 40 polonaises are dedicated to Chopin’s friend and amanuensis Julian Fontana. The final two polonaises—in F sharp minor Op 44 and in A flat major Op 53, composed in 1841 and 1842 respectively—are Chopin’s greatest essays in the form. The F sharp minor opens with ‘a rush of exasperation and surprise—and indignant pause—and then a roar of defiance’ (Ashton Jonson) before being transformed midway into a tender and melancholy mazurka. Op 53, nicknamed the ‘Heroic’, is one of the piano’s most celebrated works, a breathtaking epic which can be unforgettable in the hands of a great pianist. The introduction alone is a masterpiece, perfectly setting the scene for what is to come. Its striking central section with its descending semiquaver bass octaves is usually said to depict a cavalry charge but if it is played at the correct tempo with grandeur and majesty, as Chopin himself insisted, it is more like an approaching cavalcade. The Polonaise-Fantaisie in A flat major Op 61 was Chopin’s last extended work, written in 1846, three years before his death. By both its title and structure, it is in a class of its own. It is an exploratory, original work which, judging from the manuscript, caused Chopin some difficulty before he arrived at a satisfactory version. Although the distinctive rhythm of the polonaise is present in the opening theme, elsewhere it is often absent altogether, the ‘fantasy’ part of the title implying a feeling of rhapsodic improvisation. Through thematic recall and his innate sense of form, pacing and proportion, Chopin manages to achieve a remarkably cohesive whole. Garrick Ohlsson concludes with the earliest work on this disc, the Andante spianato and Grande Polonaise in E flat major Op 22. It exists in two versions, for solo piano (the version most frequently heard) and for piano and orchestra (the original version, and the one recorded here), the last work that Chopin wrote in this form. The polonaise section was composed in Vienna in 1830 shortly before his arrival in Paris. Perhaps tiring of the glittering stile brillante, Chopin set it aside until he had the inspired idea of prefacing it with a work of an altogether different character that he added in 1835. It is really a nocturne. Indeed it seems that Chopin may have conceived the Op 27 nocturnes as a triptych to include this work in G major. In the event he entitled it Andante spianato, ‘spianato’ meaning ‘smooth’ or ‘even’. It may be, in the words of one commentator, ‘a fairly arbitrary coupling’, but it is nevertheless wonderfully effective and the only one of Chopin’s works for piano and orchestra, other than the concertos, to have retained a regular place in the repertoire. Jeremy Nicholas © 2010