Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

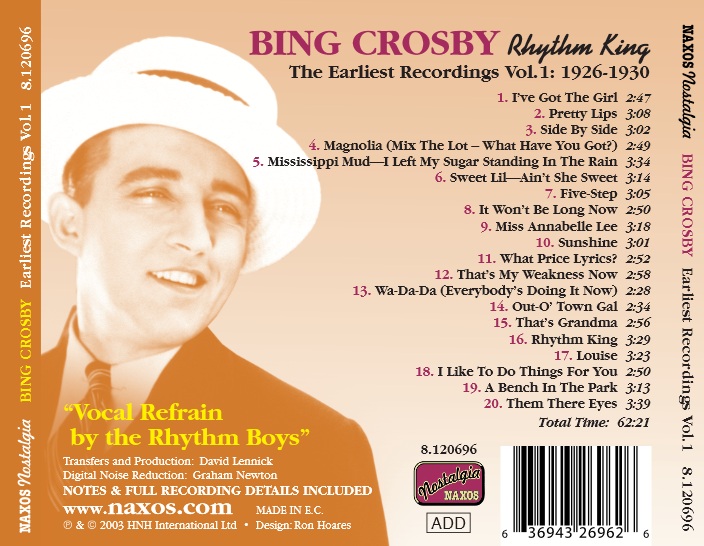

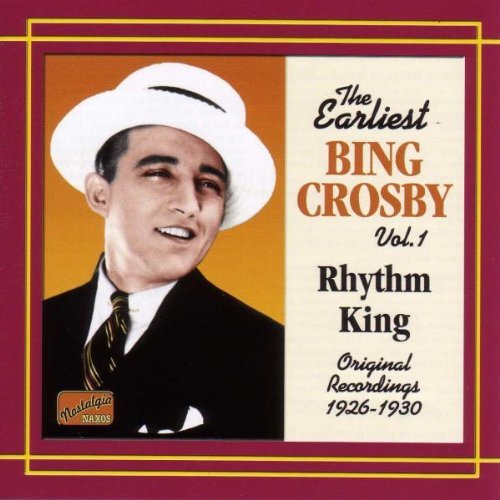

Bing Crosby

The Earliest Bing Crosby Vol. 1 - Rhythm King

- Bing Crosby - vocal

Original Recordings 1926-1930

"BING CROSBY Rhythm King The Earliest Recordings, Vol.1: 1926-1930 "Vocal Refrain by the Rhythm Boys" It is hard to believe Bing Crosby was born 100 years ago and he has been gone since 1977. Thanks to his records, his films and his re-emergence in both media each Christmas, it is as if he’s still out there somewhere, ready to reappear on a concert tour or with a new seasonal holiday television special. Gone he may be in the physical sense, but he is still very much with us. There are still facets of the man and the artist awaiting re-examination and fuller appreciation. This first of two Naxos volumes of his earliest recordings affords listeners that opportunity. It begins with Crosby’s very first recording, made in a converted Los Angeles warehouse when he was on the brink of stardom, but then just part of a passable duo with his partner, Al Rinker. They met in their hometown of Spokane, Washington, in 1924 when Rinker, four years younger than Crosby, invited him to join a band he and some friends had organized. Crosby was then a drum-playing law student at Gonzaga University. The other members of Rinker’s outfit were surprised and pleased when he said he could sing, too. After playing for school parties, dances, local theatres and any dates they could get, the group eventually devolved down to just Crosby and Rinker. When work dried up for them in the Pacific Northwest, they headed for Los Angeles. One of the attractions was that Rinker’s sister, the singer Mildred Bailey, was living there and might be able to help them. She did, indeed, and they soon became a moderately popular local act. It was during their engagement at the city’s Metropolitan Theatre they were spotted by bandleader Paul Whiteman’s manager, who recommended them to his boss while they were in town on a tour. Whiteman signed them after a meeting in his dressing room. Legally, Crosby’s recording of I’ve Got the Girl never should have been made. He and Rinker were completing their Metropolitan engagement, had already been signed by Whiteman (a Victor recording artist) and were going to join him in a few weeks in Chicago. Years later, Crosby recalled he and Rinker wanted to hear how they sounded, so they agreed to the Columbia Records session with saxophonist Don Clark and His Biltmore Hotel Orchestra. Their one side was issued without label credit and was unknown to collectors until the early 1950s, when Crosby himself recalled the event. Not long after joining Whiteman’s musical organization in Chicago, Crosby embarked on his official recording career — although still without label credit — on Pretty Lips. At this stage, the Rhythm Boys were just "vocal refrain," as far as record buyers were concerned. As with I’ve Got the Girl, there’s plenty of evidence of Rinker’s high tones and Crosby’s more solid lower tones. By his own admission, Crosby was still patterning himself after his baritone idol, Al Jolson. In time, the Jolson influence would be toned down and melded with other musical influences to produce the Crosby sound the world would come to love. But at this point, Crosby and Rinker were merely a pleasant but not earth-shattering combination. The team needed one final element, which it got just weeks later when Whiteman and company moved on to New York’s Paramount and his own Club Whiteman. Crosby and Rinker had been a hit on their own on west coast stages and they did okay with Whiteman on tour in the Mid-West. Well enough that he included them on a recording session soon after arriving in Chicago and again on four east coast sessions for Victor. Pretty Lips is from their second Whiteman session, recorded at Victor’s Camden, New Jersey, studios (actually a remake of a rejected version from the Chicago session). But in their New York début, the boys were a flop. They even wound up pulling curtains when their act got cut temporarily. Whiteman was perplexed and might have easily bought out their contract had he not liked them himself and been supported by others in the band whose judgment he trusted. Whiteman’s talented violinist and arranger, Matty Malneck, was the chief source of support, praising Crosby constantly. Eventually, the answer arrived when Malneck introduced the boys to a friend from Denver. He was Harry Barris. He had enjoyed some success as a vaudeville act and bandleader, but nothing like what he was to enjoy after Whiteman teamed him with Crosby and Rinker. As a take-off of the popular Happiness Boys on radio, they became the Rhythm Boys. The addition of Barris’ high energy and superior musicianship contributed something they badly needed. They clicked with each other immediately and their performances displayed the sheer enjoyment they got from working together. You can hear it on their first recording, Side by Side. The Rhythm Boys were a hit at Whiteman’s club and again when he presented them during a return engagement at New York’s Paramount Theatre. Whiteman, sensing a good thing, soon negotiated a separate contract for them with Victor, presenting them as Paul Whiteman’s Rhythm Boys and backing them with small groups comprised of the jazzier elements in his full band, including Malneck, Bix Beiderbecke, Red Nichols and Jimmy Dorsey. Aiding the team was Barris’ songwriting. His Mississippi Mud was the first of many hits the team would score on records and on the stage. The Barris influence would continue well into Crosby’s career as a solo act, Although all three members of the team obviously could sing, Whiteman knew Crosby was the real vocalist. Increasingly, his arrangers (particularly Bill Challis) made Barris and Rinker the comic sidekicks to Crosby as the featured vocalist. Even in the trio arrangements on this collection, you can hear Crosby becoming progressively more vocally prominent. With the value of hindsight, it is easy to hear him stepping out and away from Rinker and Barris as his confidence and technique grew. With success on the stage and on records, the Rhythm Boys eventually decided to strike out on their own. Following their work with Whiteman on the film, King of Jazz, and another tour, they parted company and soon wound up with Gus Arnheim’s Orchestra at Los Angeles’ Cocoanut Grove. The final track on this collection, Them There Eyes, was their only group effort on wax with Arnheim; the rest were all Crosby solos. The age of Crosby was dawning. And popular entertainment would never be the same. Greg Gormick, March 2003, Toronto, Ontario [Continued in ‘The Earliest Recordings’, Vol.2]"