Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

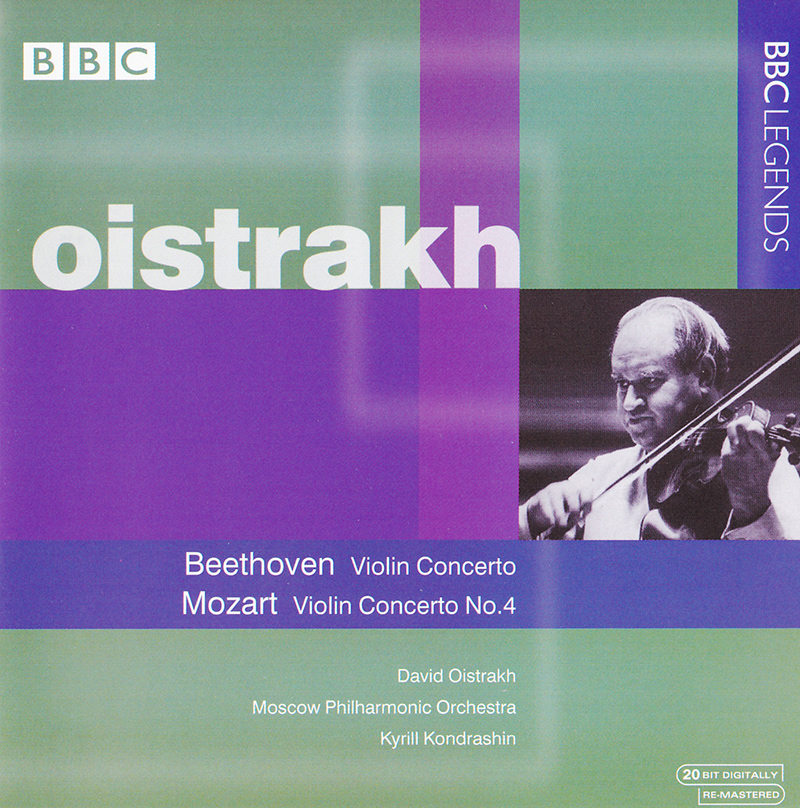

BEETHOVEN, MOZART, David Oistrakh, Moscow Philharmonic, Kiril Kondrashin

Violin Concerto in D major / Violin Concerto No.4

- David Oistrakh - Beethoven Violin cto, Mozart Violin cto No. 4

- 01. Beethoven, Violin cto in D major, Op. 61, I. Allegro ma non troppo (23:33)

- 02. II. Larghetto (8:35)

- 03. III. Rondo. Alegro (10:13)

- 04. Mozart, Violin cto. No. 4 in D major, K218, I. Allegro (9:02)

- 05. II. Andante cantabile (7:39)

- 06. III. Rondeau. Andante grazioso (7:56)

- David Oistrakh - violin

- Moscow Philharmonic - orchestra

- Kiril Kondrashin - conductor

- BEETHOVEN

- MOZART

David Oistrakh is caught here in concert at the Royal Festival Hall in October 1965. He was fifty-seven and still at the peak of his fame when he gave these two concerto performances, two days apart, with the touring Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra under Kyrill Kondrashin. Sound quality is good and Oistrakh is in good technical form, whilst audience participation is not greatly audible and only occasionally so in the Mozart when one or two bronchial coughs break out. In a discographical sense of course we are fortunately placed with Oistrakh’s Beethoven. He recorded it commercially with Gauk, Abendroth, Ehrling and Cluytens with live broadcasts having appeared under Abendroth (in 1950) and Gui from Milan in 1960. As for the D major Mozart he set it down in the studio with Kondrashin and Ormandy along with the set of self-conducted concertos he made in Berlin. The Concertos in G and A always featured more prominently both in concerts and in the recording studios. But no Oistrakh live performance should be scorned and these have the usual array of virtues. His opening movement of the Beethoven is rather slow with a somewhat romanticised initial impress from Kondrashin. But even despite moments of questionable intonation Oistrakh’s occasional metrical daring is laudable, though in the passage from 18.00 his playing becomes distinctly becalmed. The slow movement is affectionate and complexly moving, though not as much as the performance with Cluytens - and there are some tentative moments at the end of the movement. The finale is propulsive and the partnership with Kondrashin is strong – but there are some examples of rough passagework from the soloist and some stress at the end. The Mozart is an inscription in Oistrakh’s best and most stylish classical approach. It is strongly etched, certainly, and those familiar from his other recordings of this concerto, noted above and in the context of his Mozart playing generally, will probably anticipate his approach. This is a strong and robust reading and he employs the David cadenzas. His slow movement for example is delightfully done but doesn’t have quite the sense of repose of Szigeti/Beecham or the sheer elegance and charm of Thibaud, to take just two violinists of a slightly later generation. The finale is genial but not especially impressive, though on its own terms it’s marvellously integrated as a performance. The notes are by the ubiquitous Tully Potter and the remastering is fine. This collection of the two D majors brings us a glimpse of a stellar talent – not always perfectly, it’s true, but still admirably – and expands his discography ever more tantalisingly outward. Jonathan Woolf