Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

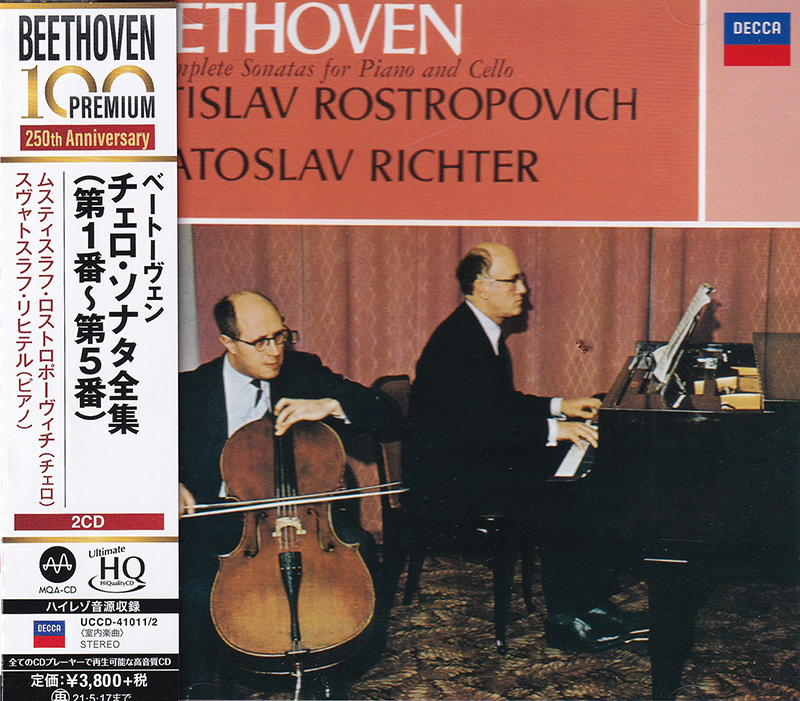

BEETHOVEN, Sviatoslav Richter, Mstislav Rostropovich

The Complete Sonatas for Piano and Cello

- Sviatoslav Richter - piano

- Mstislav Rostropovich - cello

- BEETHOVEN

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Since it first electrified me nearly 40 years ago, the commercial recording of the Beethoven Cello Sonatas by Richter and Rostropovich (made for Philips between 1961 and 1963) has been one of my touchstones—easily my favorite account of this music. The two artists are so obviously in sync, both musically and emotionally, that it came as a shock to learn that they hadn’t worked out their interpretations through dozens of joint concerts. It’s not simply that those Beethoven sessions didn’t come as the climax of a series of public recitals. Even more surprising, the cello sonatas were tangential to Richter’s repertoire. Indeed, the 1964 Edinburgh concert documented on this DVD was the only time he played any of this music in public after the 1950s (except for one other performance of op. 69).

It was even more of a shock to discover that the bond between the two musicians was far from ideal. Overall, Richter seems to have been put off by the self-promotion of this “almost great” cellist (Bruno Monsaingeon, Sviatislav Richter: Notebooks and Conversations, Princeton University Press, 2001; p. 339). Richter was, for instance, never able to forgive Rostropovich for convincing Prokofiev to rewrite a portion of the finale of the Sinfonia concertante in order “to create more of an impression” (p. 65). He resented, too, the way Rostropovich fawned on Karajan during their recording of the Beethoven Triple. And his reaction on hearing a recording of Grieg and Brahms from a recital they gave in Aldeburgh a few months before this Edinburgh concert is telling: “Slava was so afraid that I’d drown him (!) that he managed to talk me into lowering the piano lid. The result is a frightful imbalance and, at the same time, there’s a general impression of overcautiousness. . . . An execrable recording” (p. 235). Significantly, at the beginning of this recital, we see the page-turner lower the piano lid. Obviously, Rostropovich was still pressing the point.

And yet, whatever the strife, the performances are just as magisterial, just as unified, and just as gripping as you could wish. And just as compelling as the more familiar Philips recordings. Indeed, given the apparent spontaneity of these two artists—and given Richter’s tendency to freeze during recording sessions—the interpretive match between the two sets of performances is hard to believe. As usual with Richter’s Beethoven at this point in his career, the interpretations are high strung and volatile—no subtle probings, no sign of reverence (even in the elaborately fugal finale of the Fifth), and certainly no Classical reserve. But the forward pressure never squashes detail, just as the moment-to-moment intensity (the central movement of the Fifth will wring you out) never obscures ingenuity of the music’s large-scale design. Dynamics are especially well handled—exquisitely shaded, but never finicky (listen, for instance, to the breathtaking handling of the oasis just before the end of the finale of the First, mm. 257 ff.). Rostropovich matches him in virtuosity and emotional concentration—as well as in interpretive detail. Strange alchemy, no doubt—but whatever was going on, we are the beneficiaries. As a bonus, we’re given a Moscow recording of Richter searing his way through Mendelssohn’s Variations sérieuses—a work he played often but never officially recorded (although a performance from Brooklyn has shown up now and then). The filming is minimalist—black and white, few camera angles. This serves the occasion well: Our attention is on the performances, not the capabilities of video editing. One chapter break is misplaced, and the sound is only so-so—but I doubt anyone attracted to this kind of issue will complain. Does this DVD supersede the studio version of the Beethoven? Probably not for everyone: Certainly, some readers will appreciate the way Richter’s sound carries more clearly on Philips. But for others, I suspect the visual component, the sense that we’re actually at a concert, will more than compensate. Either way, a classic set of interpretations.

Peter J. Rabinowitz, FANFARE

UHQCD oznacza Ultimate High Quality Compact Disc. Najnowszy (lipiec 2018) materiał chroniący warstwę nośną płyt kompaktowych, opracowany przez specjalistów z Japonii i Hong Kongu. Na krążki tych płyt nanoszona jest cienka warstwa z monomerów oraz wypełniacza. Warstwa ta nie stanowi bariery dla światła lasera. Promień lasera jakby nie dostrzega owej warstwy ?fotopolimeru?, a więc nie ulega rozproszeniu, załamaniu, odbiciu. Promień sięga po czysty sygnał i w takiej, nieskazitelnej postaci wraca z nim do źródła. Zdaniem specjalistów ? to najwierniejszy z dotychczasowych sposobów na przeniesienie analogowych walorów taśmy matki na płytę CD.

Dziś.

Płyty UHQCD są dodatkowo kodowane jako MQA (Master Quality Authenticated). Wystarczy wyprowadzić sygnał cyfrowy z cyfrowego wyjścia odtwarzacza CD lub wcześniej zgranego strumienia danych z serwera muzycznego i podać go do odpowiedniego konwertera MQA DA by wygenerować z danych umieszczonych na tej CD 24-bitowy sygnał z częstotliwością próbkowania do 352 kHz.

Do wyprodukowania limitowanej serii płyt UHQCD wykorzystano dane DSD z jednowarstwowych płyt SACD (One Layer), wydanych przez Universal Japan w poprzednich latach. Wydania te stanowią szczytowe osiągnięcie fonograficzne ostatnich lat. Niestety, dostępne wyłącznie dla posiadaczy odtwarzaczy SACD. Płyty UHQCD są idealnym rozwiązaniem dla melomanów, którzy nie mają playerów SACD, a chcieliby delektować się jakością legendarnych już japońskich SACD One Layer.

Płyty UHQCD - w naszej ofercie

UHQCD oznacza Ultimate High Quality Compact Disc. Najnowszy (lipiec 2018) materiał chroniący warstwę nośną płyt kompaktowych, opracowany przez specjalistów z Japonii i Hong Kongu. Na krążki tych płyt nanoszona jest cienka warstwa z monomerów oraz wypełniacza. Warstwa ta nie stanowi bariery dla światła lasera. Promień lasera jakby nie dostrzega owej warstwy ?fotopolimeru?, a więc nie ulega rozproszeniu, załamaniu, odbiciu. Promień sięga po czysty sygnał i w takiej, nieskazitelnej postaci wraca z nim do źródła. Zdaniem specjalistów ? to najwierniejszy z dotychczasowych sposobów na przeniesienie analogowych walorów taśmy matki na płytę CD.

Dziś.

Płyty UHQCD są dodatkowo kodowane jako MQA (Master Quality Authenticated). Wystarczy wyprowadzić sygnał cyfrowy z cyfrowego wyjścia odtwarzacza CD lub wcześniej zgranego strumienia danych z serwera muzycznego i podać go do odpowiedniego konwertera MQA DA by wygenerować z danych umieszczonych na tej CD 24-bitowy sygnał z częstotliwością próbkowania do 352 kHz.

Do wyprodukowania limitowanej serii płyt UHQCD wykorzystano dane DSD z jednowarstwowych płyt SACD (One Layer), wydanych przez Universal Japan w poprzednich latach. Wydania te stanowią szczytowe osiągnięcie fonograficzne ostatnich lat. Niestety, dostępne wyłącznie dla posiadaczy odtwarzaczy SACD. Płyty UHQCD są idealnym rozwiązaniem dla melomanów, którzy nie mają playerów SACD, a chcieliby delektować się jakością legendarnych już japońskich SACD One Layer.

Płyty UHQCD - w naszej ofercie